It was 2009 when I was first introduced to the Neo-Miniature in Pakistan. I was a first year student at Brandeis University, and enrolled in Introduct

It was 2009 when I was first introduced to the Neo-Miniature in Pakistan. I was a first year student at Brandeis University, and enrolled in Introduction to Drawing. I was the only South Asian student in the class, and my excited professor asked if I knew who Shahzia Sikander was.

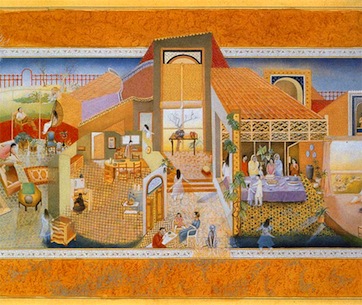

I replied with a blank stare. I had never heard of the name. It was now exactly 17 years since she had graduated. I quickly Googled and was met with a mélange of images of Buddhas and young men and dancing figures all beautifully and intricately painted on small pieces of paper and delicately handled.

This was my first knowledge of the history of Pakistani art, and it is a testament of the strength and global reception of the Neo-Miniature movement of Pakistan that my introduction was through it.

Shahzia Sikander is part of a group of painters within the neo-miniature movement that Virginia Whiles, who wrote the groundbreaking text Art and Polemic in Pakistan: Cultural Politics and Tradition in Contemporary Miniature Painting, classifies as Group X. She says that their ‘opting to contest rather than follow the orthodox path of miniature-making taken by the majority of students (which she describes as Group O), is a radical step’ (Virginia Whiles, Preface, XXI). That group of initial young graduates of the NCA in the early 1990s includes not only Sikander, but other internationally renowned artists such as Imran Qureshi, Ambreen Butt, Saira Wasim and so on, many of whom became part of the diaspora. The phenomenon of the links between the artists of the so-called neo-miniature movement and the creation of a powerful artistic Pakistani diaspora has not been written about in as much detail as it deserves.

The story of that rich period of cultural flowering in Pakistan (the early 1990s), follows that Shahzia Sikander, after winning all the awards on offer at NCA for her thesis work at the NCA that ‘subverted tradition’, went to the Rhode Island School of Design to finish her Master’s and from there went from strength to strength. She was the first Asian woman to show at the Whitney Museum of Art. Her work was collected by giants such as the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), and the peak of 2006, she won the MacArthur Genius Grant, a five-year, $500,000 award given to 20 individuals .

It has been claimed that due to Sikander’s success, she inspired a generation of students at the NCA to take up miniature painting and revive the craft and subvert tradition in their own way, thus leading to the establishment of the so called neo-miniature movement. This claim can be challenged in some way in the sense that a crop of young artists such as Imran Qureshi, Ambreen Butt and Faiza Butt graduated a mere one year after Sikander – while they were likely inspired by her thesis work, their selection of miniature painting could not be reflective of Sikander’s as yet unattained success. It must also be noted that while Sikander, Ambreen and Faiza Butt, and many others chose to leave the country and thus became part of the very powerful Pakistani diaspora artistic community in the West, Qureshi continued practicing and teaching in Pakistan, eventually becoming the head of the Miniature Department at the NCA, a position that he holds today.

Imran Qureshi is another artist who has recently attained great success in the global world, and thus furthered this movement. His recent commission for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was arguably one of the highest profile works by any Pakistani artist globally. The work which borrowed the title of a line from Faiz’s poem ‘And How Many Rains Must Fall Before the Stains are Washed Away’ is a reflective look at the current condition of the Pakistani state, from afar a pool of blood, that evokes traumatic events such as the aftermath of a bomb blast. Upon closer viewing, one sees small minute flowers, a direction of hope – from violence comes regeneration and vice versa, the interlinking of both in our society.

So the neo-miniature movement can thus be classified as simply a subversion of tradition. The artists have been inspired by, influence from, and engaged with the contemporary political and social milieu of Pakistan to create works that excite and astonish. Their works deal with themes as diverse and global as any – Saira Wasim discusses the hybridization of her identity, Faiza Butt deals with gender, Imran Qureshi with violence, Madiha Sikander with the media, and so on. The possibilities are endless and the fascination continuous.

Despite the recent controversy around the subject of art history in Pakistan, and who must be included and excluded from it, it is of no dispute that the early group of artists in that rich flowering period of the 1990s created together a lasting movement that has been Pakistan’s greatest contribution to global art history. In all nations, there is a rich flowering period, and the 1992-1995 era could be one such that. It would be interesting to explore the particular reasons and influences for that, but one such person that many artists turn to is Zahoor ul Akhlaq, that underrated Pakistani artists who many say was on the cusp of both modern and contemporary. Artists such as Rashid Rana and Shahzia Sikander today regularly point to him being one of their main inspirational figures – he was certainly influential in the establishment of a strong miniature department at the NCA, but he was also important because he freed them from the constraints of this contested identity of Pakistan. Akhlaq’s mentorship allowed artists to break from this question of ‘What is So Pakistani About This Painting’, and in turn explore the global possibilities that art could turn to.

Much academic research still needs to be done in this movement of Pakistan – the influence of Zahoor ul Akhlaq, the question of neo-orientalism, the strong relationship of the market to this particular art form, and where is it headed in the future. Were the 1990s its peak point, and are we now seeing a saturation? Are the current artists just studying miniature because they want to sell? Can the tradition be subverted further, or do we need to subvert the subversion? These are the questions that the Pakistani artistic landscape must come to terms, now, close to 25 years on.♦

Aziz Sohail is Studio Director for Rashid Rana Studio and an independent curator and critic based between Karachi and Lahore.

COMMENTS