The following essay takes form in small short linked vignettes that trace this rather muddled concept of inspiration – from the idea of identity, to P

The following essay takes form in small short linked vignettes that trace this rather muddled concept of inspiration – from the idea of identity, to Pakistani ustad-shagird relationships, to the rather important influence of Zahoor ul Akhlaq, to my own experience of teaching at the NCA. I hope that these linked ideas create a larger narrative for the complicated notion of inspiration within the context of art history and Pakistani artistic landscape.

Identity and Inspiration

The notion of an inspiration of an artist is quite curious because it is in such a way that an artist can get classified in terms of nationality, identity, and be classified in a binary identity box. It is important to note that living in a globalized world, what defines a Pakistani artist may very well be the concept of inspiration. Quddus Mirza has eloquently stated that “’What is your identity’ – One hears this phrase so often at different ports of travel, points of entry, places of official significance, and on the Internet, that one is reluctant to respond with another query, ‘What is Identity?’” (Mirza, Labyrinth of Reflections, Catalogue Essay).

Mirza goes on to continue answering this notion of identity, noting that this has undergone transformations, coming to note that an individual has multiple identities, but that a notion of individual identity is not only damaging but impossible. (Ibid) I argue, coming from this point, that individual identity is constructed in the concept of art, around the notion of inspiration. An artist’s identity is also rooted in his or her source of inspiration and thus ultimately linked to that. One is well aware of the many young artists in the 1990s, most significant of whom is Rashid Rana (explored further in detail in this essay), who were directly inspired by Zahoor ul Akhlaq and resist being classified in a binary identity – however, Pakistani artists regularly get put in a pigeonhole, where they are supposedly inspired by violence and upheaval and current issues of their time, that define the anxious Pakistani state.

A cursory Google of ‘Pakistani art’ and ‘inspiration’ reveals some curious articles coming out especially from the rather art historically important (at least in the Pakistani context) exhibits of contemporary Pakistani art at Asia Society, New York, curated by Salima Hashmi and at Mohatta Palace Museum, curated by Naiza Khan. It was intriguing to observe that such articles had interest (and can one say problematic?) headlines such as ‘Pakistani artists find inspiration in turmoil’. Are we Pakistani artists identified then by our inspiration in turmoil?

Ustad-Shagird Relationship

A key bulwark upon which inspiration can be based in Pakistan is the ustad-shagird relationship, which rests upon mentorship, devotion, inspiration and learning. At its core, the idea rests upon the teacher (or the ustad) passing on knowledge to his student (or the shagird). In the relationship, the ustad acquires a status of mentor, where the student looks to him for inspiration, and he nurtures the skills of the student. This type of relationship has been present since the time of Mughal era in Pakistan and has served to deeply allow us to understand the modalities of our current ideas of where we are headed. It is in thus such a state that inspiration has come from our masters and our mentors.

In the context of Pakistan, the ustad-shagird relationship continues to be important. Many spaces such as the Naqsh School of Arts focus on this relationship in creating a continuous body of work that is rooted in its practices and traditions. Observing our miniature and calligraphy traditions, one can discuss the concept of inspiration deeply manifested through our history, a practice that continues to this very day. Upon the recent death of Khalid Iqbal, noted Pakistani landscape painter, multiple students of his came forth expressing sadness at the passing of their mentor. Whereas in the Western world, skills such as landscape painting have been acquired from the academic sphere, through specific course modules, in spaces such as Pakistan the reality is different. Many young calligraphers or landscape painters never go to institutions such as the NCA and acquire their skills over a long period of time from their ustad, foregoing the concept of this formal degree or education program.

Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Rashid Rana

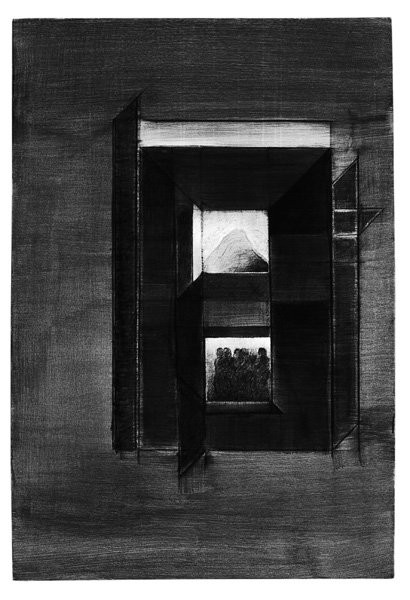

One of the greatest and most enduring relationships of the mentor-student in our recent Pakistani art history can be the relationship of Zahoor ul Akhlaq with Rashid Rana. This fact was made apparent and discussed widely in Rashid Rana’s recently closed solo exhibition at Mohatta Palace Museum, ‘Labyrinth of Reflections’. In an interviewwith Hans Ulbrich Oberst, when questioned about his inspiration, Rana noted that “the most visible influence on my work is that of Zahoor ul Akhlaq.”

The curator of the exhibition, Naazish Ataullah, discussed at length the influence of Zahoor ul Akhlaq, on whom less than deserved has been written about but who is arguably one of the leading artists in the gamut of modern and contemporary Pakistan art, located in art historical terms at the “interesting juncture between modernism and the post modern”. Akhlaq in contemporary scholarship is quite easily added as a footnote as being the inspiration and driving force behind the so called revival of the miniature painting department and is credited with being important in the creation of a ‘neo-miniature artistic movement’ but his mentorship role goes far beyond this much-talked about contribution. Ataullah is careful to note that “his [Akhlaq’s] importance is primarily due to this powerful and visionary work, but also for his role as an unusually sensitive teacher and mentor who inspired generations of students at the National College of Arts”. Akhlaq is known to have allowed students to come over to his studio multiple times, something that allowed artists such as Rana to observe his work closely. Ataullah notes that “Rana attentively assimiliated the concerns that Akhlaq’s own investigative practices revealed to him”. But rather than just showcase his work, Akhlaq went further – going with his students to the Walled City, introducing them to his favourite hang-out spots there, and discussing diverse topics of literature, music and dance. Discussions at his house of friends and students tended to be spirited but relaxed, allowing artists to share ideas and knowledge.

In such a way, Akhlaq’s relationship to his students, especially Rana, can be traced back to his own relationship with his mentor Shakir Ali. Shakir Ali is credited for being especially influential in introducing cubism in Pakistan, especially amongst some of the students he mentored such as Bashir Mirza, Ahmed Pervez and Jamil Naqsh. Shakir Ali was eminent and influential in his era in “Lahore’s small circle of intellectuals that comprised artists, poets, and writers, active participants in postcolonial modernist discourse”. He brought Akhlaq on board at the NCA, a visionary decision, given that Akhlaq would eventually become the Head of the Fine Arts Department. In this period, thus, the NCA was a particularly rich incubator of ideas and influences that continued to inspire new generations of artists in multiple ways.

Education at the NCA

Undoubtedly, then, the NCA becomes an important space in the Pakistani historical context in spreading inspiration and ideas within the artistic landscape. As a faculty member at the NCA, one can easily observe bonds of ustad-shagird present in the relationship between many students and teachers. In the Miniature Painting Department for example, the influence of Imran Qureshi, Shazia Sikander and other eminent artists is widely felt, cherished and discussed – a phenomenon even directly documented by Virginia Whiles. Whereas artists such as Imran Qureshi have been influential since the 1990’s, involved in the direct education of the students, those such as Sikander continue to inspire due to their groundbreaking vision to subvert tradition and the international success they achieve. In such a way, the Miniature Department rests upon a strong base of the recent past continuing to inspire and mentor the students.

Such phenomenon is also part of the Painting, Sculpture and Printmaking Departments. I have already briefly traced the inspirational role of such artists as Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Shakir Ali, but artists such as Atif Khan, Afshar Malik, Quddus Mirza and more continue to shape their students ideas through strong mentorship and engagement. It is an important notable fact, in a country, with limited artistic resources the outsize role that the NCA has played in shaping movements and ideas within Pakistan.

Conclusion

Thus, when one touches upon the concept of Inspiration in Pakistani art, the notion itself can be quite complicated. Linked to our ever continuous search for identity in art, inspiration is directly affected by the unique artistic landscape of Pakistan – the presence of ustad-shagird relationships, the outsize influence of the NCA, and the presence of powerful strong mentors such as Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Shakir Ali. One needs to look at these multiple strands much more in depth to further continue understanding these concepts, and in doing so, trace the comprehensive canon of Pakistani art history – something still waiting to be written at length.

Aziz Sohail is Studio Director for Rashid Rana Studio and an independent curator and critic based between Karachi and Lahore

COMMENTS