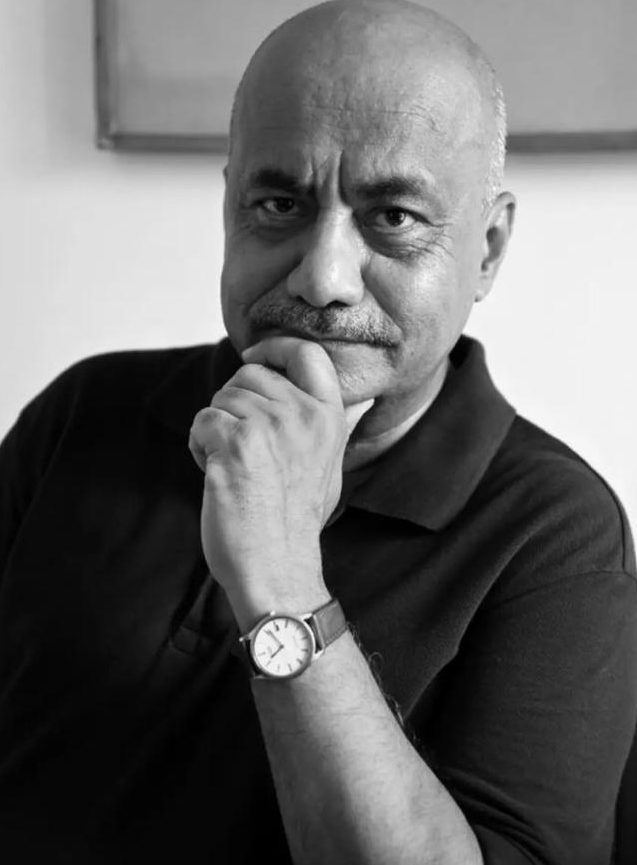

Rasheed Araeen is a step further into deconstructing a powerful, perfect and precise structure, in order to make your own sense of the world. Bu

Rasheed Araeen is a step further into deconstructing a powerful, perfect and precise structure, in order to make your own sense of the world.

Burning a country’s flag, a normal practice in our society, is an unlawful act in others, especially the USA. Desecrating the American flag is considered as sacrilegious as ripping its constitution, defacing the pictures of its founders, or even slicing its currency bill. Yet there is an artwork, a set of 12 photographs, that records the stages of an American flag put to flames; currently on display at the Tate Britain.

This piece, Fire, that Rasheed Araeen produced in1975, incorporates a manipulated US flag – where instead of stars, you find fighter planes, and a text, half scrawled half composed, spread on stripes, that reads ‘Down with American Imperialism’. The sequence of pictures starts with the linear drawings of the US flag and ends on the entire flag burnt (thus disappeared), revealing the flag of Vietnam, with a snapshot of its freedom fighters inside the central star.

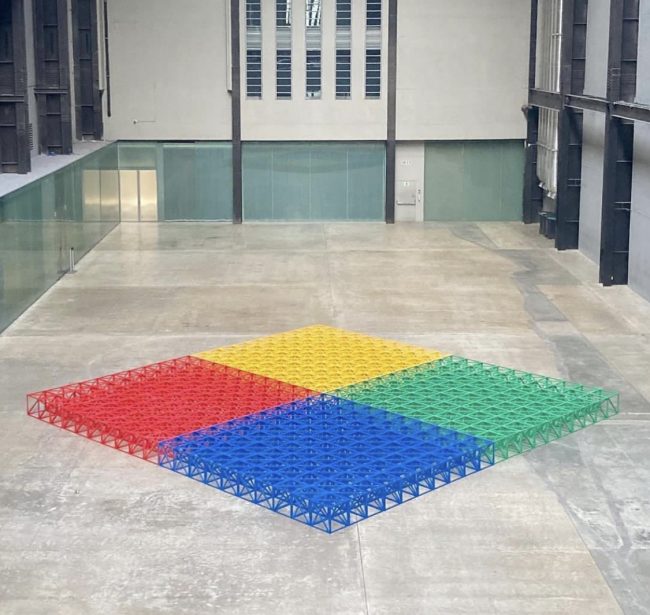

It clearly rerefers to the Vietnam war and the US imperialism, but the act of destruction and creation assumes another meaning, when viewed in the context of Rasheed Araeen’s latest work at another Tate, the Tate Modern. Here Araeen arranged a monumental piece of sculpture – made out of 400 units in the Turbine Hall, the most iconic space of the UK’s leading museum. Placed in a symmetrical manner, the work soon started to alter its form, layout and dimensions, first by the maker who led the initiative of disarraying similar blocks, followed by everyone present on the opening day (21st June 2023), and continued afterwards by numerous visitors. It has been informed that the UNIQLO Tate Paly: Rasheed Araeen (on until 27th August 2023) is one of the most visited project, with people waiting in queues to dismantle it further, hence create their own compositions; and participate in the course of its perpetual metamorphosis.

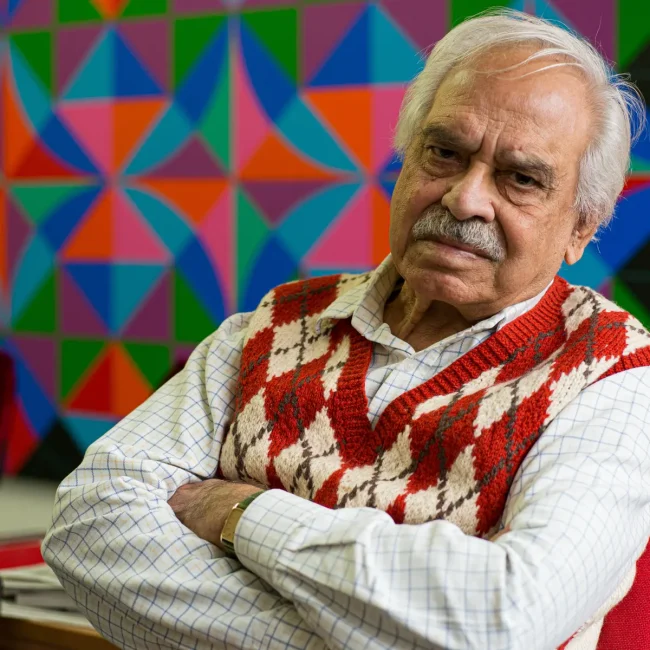

The installation is composed of latticed construction cubes of identical size, equally split into four vivid and pure colours (red, yellow, blue, green). Their straight and diagonal lines slice the inner space and prompt a web of infinite lines when put randomly inside the Turbine Hall. This work, Zero to Infinity, relates to Araeen’s earlier drawings and paintings based upon the rendering of wind-catchers of Hyderabad Sindh (1962-63), subsequent installations (for example To Whom It May Concerns, 1996, Serpentine Galleries London), and his recent sculptures in wood included in exhibitions, art fairs, biennales, and triennials.

Araeen has been producing a number of paintings, based on geometry, which denote the names of Muslim philosophers, scientists, mathematicians, including the twelve-thirteen century Andalusian philosopher Ibn Arabi. In a sense Ibn Arabi’s doctrine of Wahdat ul Wujud, in which the “external world of sensible objects is but a fleeting shadow of the Real (al-Haq), God”, can be compared to the medieval Muslim image makers’ act of translating the visible world into primordial shapes. Following this, Araeen’s work at the Tate Modern is a step towards recognizing the presence and potential of infinity (or the Real) in diverse manifestations, forms, combinations, colours, through the course of geometry.

Araeen’s (apparently) formal/structural/geometric installation requires some reflections and interpretations. The interactive work at Tate Modern culminates to his life-long quest to wrench art out of institutional domain. Particularly liberating it from a white dominance that overshadowed the art world of the sixties, seventies and eighties. The exhibition The Other Story that he curated at Hayward Gallery in 1989-90 was a pivotal point in this regard, since it represented artists from Asia, Africa and the Caribbean at a mainstream art space of the UK. Araeen carried out his crusade to destroy the structure of art based upon discrimination, marginalization, exclusivity, and racial prejudices. Not only his art, but his writings, and his journal the Third Text (copies of its volumes and his other books are available for public at the Bridge, Turbine Hall) fought for a just society with an equal opportunity in spite of one’s odd accent, dark complexion, strange attire, unusual manners.

The project of Rasheed Araeen, which has been previously installed at various venues including the 57th Venice Biennale (2017), is about accepting, admitting and inviting people of every colour, race, gender, age, class to become a participant, a collaborator, a creator in the making of an artwork at the Tate Modern, hence subverting and shattering the system of art establishment. And empowering those, who once in front of valuable canvases, ambitious installations, video projections feel an outsider, like a passive consumer. The work displayed at the Tate began in 1968, and in a text from that year, Rasheed Araeen invites the viewers to: “Touch these structures with your hands; manipulate them….. You can continuously create new relationships by constantly changing space by playing with these structures … put them on top of each other. Spread them horizontally”.

The sculptural installation of Rasheed Araeen is deeply connected to his lifelong struggle to make the voice of ‘the Other’, an outsider, an outcast, a foreigner heard in the corridors of western art establishment. Weeks before Araeen’s project at the Tate Modern, another exhibition illustrated this side of his personality. The solo show of selected works; ‘Rasheed Araeen: Sixty-Three Years of Figural’, June 30 – July 15, 2023, Grosvenor Gallery (at Frieze, 9 Cork Street London) offered exhibits from different phases of Araeen’s long and intense career. These, works from 1960 to 2023, included pastel, ink and pen on paper, photographic prints, collages, sculptures, films recordings of his performances – and text on paper.

Though Araeen’s Grosvenor Gallery exhibition was conceived around figure (mentioning Figural), yet the works collected, revealed major concerns of the maker. The imbalance of power, West against East, males controlling the female, the rich subjugating the poor; and the elusive world of art in comparison to ordinary existence. One was able to locate these threads, beginning with Araeen’s earliest pastel on paper (Matrimony, 1960), a stylized/Cubist composition of a mother and child, accompanying another work (Male Ego, 2007), that comprised of an enlarged print of the initial pastel, added with 6 text frames, all referring to infantile male ego describing its maladies of overpowering, oppression, violence.

Male, or white male, or dominating white male, is a subject Rasheed Araeen approached again and again, questioning its oeuvre. The Grosvenor solo exhibition was about human figure, yet one could see that Araeen used the idiom of body to convey the issues of power, tyranny, and prejudices, especially related to race. In his performance Paki Bastard (Portrait of the Artist as a Black Person) made in 1977, and comprising of “forty projected images/slides and sound, 25 minutes” Araeen referred to once regular and widely uttered hate speech. The clash between the white population and those who migrated from the colonized countries of Asia, Africa and Caribbean manifested in this and many forms.

In bloody confrontation too; as documented by the artist in a photographic collage (When They Meet,1973) of protestors on the road, and the police force on their steeds. These photographs are not just journalistic snapshots, but create the cartography of mighty power next to nobodies. Seen today, they almost remind of Milan Kundera’s writings, in which a mundane occurrence, or object has the potential to narrate the entire structure/system of suppression, and to deflate it; as witnessed in this group of 20 pictures. In one photo a cop standing close to formation of armed personnel, appears to be sneezing in his handkerchief; and so is another picture with two sides of men – the British police and the immigrant agitators – with a cap of some officer lying in the middle on the ground.

This relation – that often turns sour, is one of the recurring motif in Araeen. But instead of being a direct dissentient, he sought a diction that digs deep into the psychology of this unjust equation. Human body, as seen in one after another work at the Grosvenor Gallery’s show, is a field of injustice. It is a tool of exploitation too. How the former colonial rulers manipulated the conquered societies through objects, images, ideas, and language. And how the illusion of beauty, perfection and goodness is still projected in the minds, souls, bodies and the wallets of large population of the world, no matter from the former colonies or surviving in the ghettos of the first world.

One example. In an image from the group of 4 collages (The Golden Series, 1974-78), you come across a grid of six naked women posing for porn magazines. Araeen cut their faces, added ideal proportions in blank areas, and pasted the removed pieces by reversing them/their identities at the base of the work – next to another photograph of a female working in a field. The caption reads ‘Must we always wait for pictures like this?’. The work reminds the split of the world in haves and have-nots, in prey and predator, in aggressors and victims. Identified with the resistance against the western imperialism, Rasheed Araeen, in a series of 9 discs, It was the Time (1975) combined words of Ho Chi Minh with visuals of Vietcong warriors.

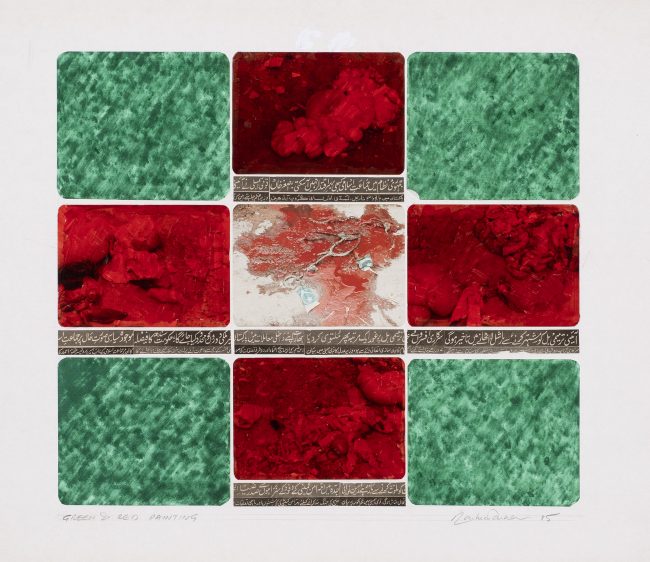

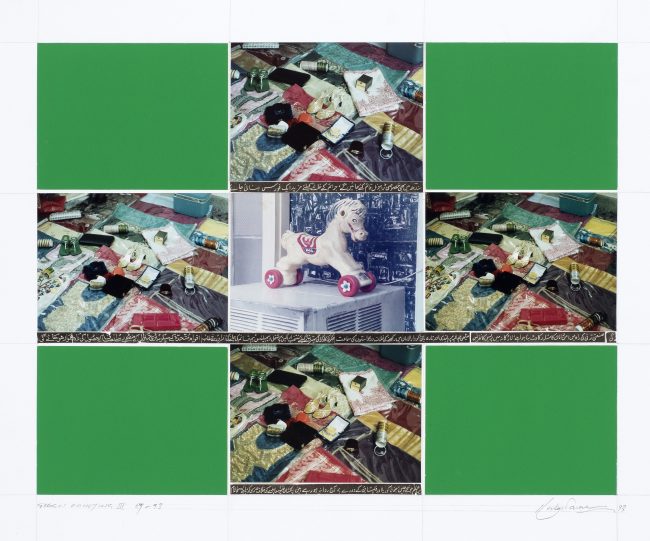

Whether man or woman, white or coloured, colonial or colonized, the dichotomies that considered normal in nature/past but become the instrument of supremacy and subjugation, are the keystones of the grand architecture of Rasheed Araeen’s aesthetics. He chose another formal device to communicate his ideas – through another national flag. In his collages (6 installed at the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition) the artist used the format of English flag. The cross in all these works had green rectangles on four sides, whereas its shape illustrated scenes of sacrificial slaughter of Eid ul Zuha; newsprint cut-outs of toys and part of dowery stuff; commercial advertisements and TV footage of the Gulf War; Salman Rushdie brandishing his most controversial novel and the graffiti against him and denouncing the US; as well as a central painting consisting of an indigenous nude next to a section of Araeen’s bookshelf, the news item of Serbian attacks, and two expressively rendered canvases (all three paintings he picked from a heap of discarded stuff in London!).

In all of these works, the foundational structure – the English flag, is a cross; and the cross is the real content of these varying artworks. Jesus was crucified in Palestine (in his Falisteen, 1974, Araeen placed his picture of collecting funds for Palestine after 1973 Arab Israel war; but the title indicates the way this disputed land is spelled by its Arab inhabitants). Crucifixion for believers was an act of atrocity by Romans, that eventually emerged for the believers to be a means of redeeming the human race. Transposing this religious metaphor into contemporary politics, Rasheed Araeen signified other scarifies, other victims, other oppressors, and probably other salvations. The fact that the adjoining areas in the English flag’s cross are green suggests a clash between the two views of the world. Not different from the perception of events from the position of a coastal guard, and of a refugee trying to reach the shores of Southern Europe. Both look at each other uncomfortably, suspiciously, threateningly.

From the US flag to the English flag, the quest of Rasheed Araeen has been to shatter the palaces of power. Structures that have been regarded absolute, strong, almost eternal in the vocabulary of world politics were disjointed in his art made in multiple mediums, formats, scales.

One feels that the UNIQLO Tate Paly: Rasheed Araeen is a step further into deconstructing a powerful, perfect and precise structure, in order to make your own sense of the world. Or devise your own world. Whether you are a child playing in the Tate Modern’s space, or an immigrant trying to connect, compose and comprehend his/her life at a foreign soil – both exercises are challenging, difficult daunting, yet empowering, liberating and satisfying.

COMMENTS