The solo show stemmed from the artist’s research, highlighting the royal dynasty and its many fascinating aspects — a presentation well worth seeing.

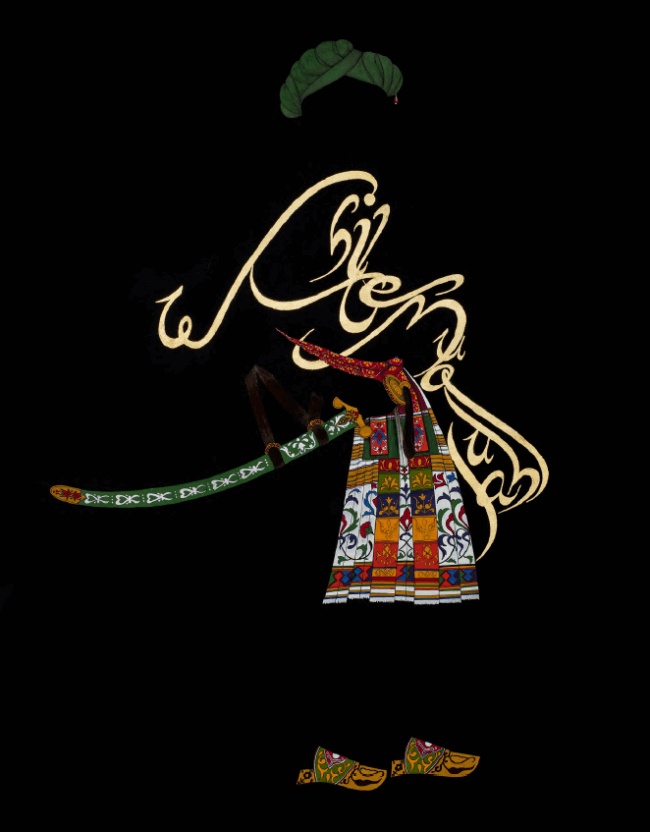

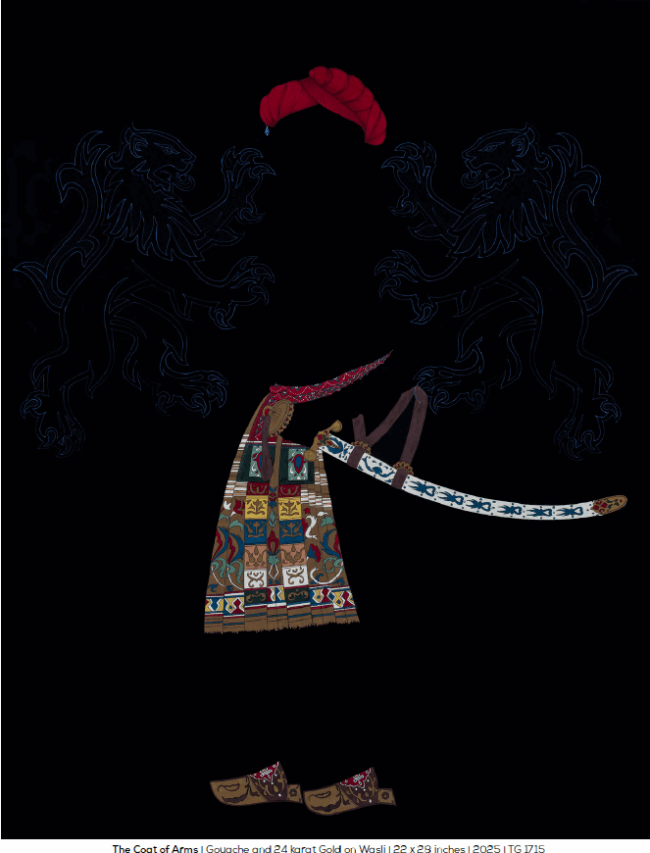

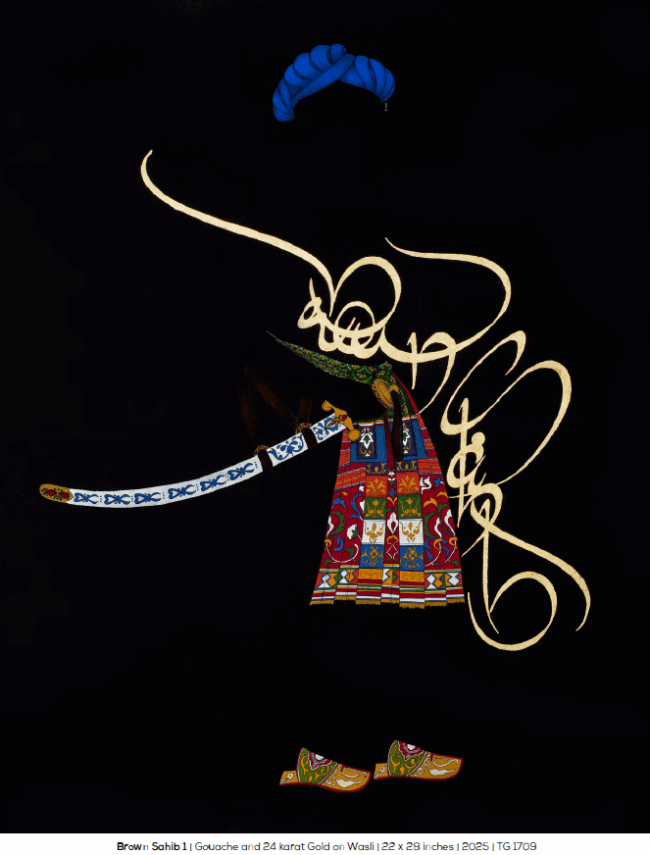

The solo exhibition of Shoaib Mahmood, titled “The Brown Sahib”, that opened at Tanzara Gallery of Islamabad, re-imagines the precolonial grandeur and how the Raj impacted the identity of royalty in the subcontinent’s context. Large black wasli frames of invisible figures, with all their regal paraphernalia and dazzling jewels, are juxtaposed with gold calligraphy, creating some stark throwbacks to the nawabs and maharajas of bygone times. Much deeper than the decorative value of Shoaib’s meticulously adorned art are the questions that he raises through “The Brown Sahib” about the complex dynamics of identity, power and history.

Shoaib has used the medium of miniature while departing from the conventional scale associated with the style. His canvases are large and imposing and the juxtaposition of certain words and phrases with royal silhouettes, once used to exert control and dominance, lends new meanings and connotations to the politics of two clashing forces. By taking Mughal figures out of their traditional contexts, Shoaib Mahmood draws attention to the stark contrast between pre-colonial splendor and the complicated inheritance left by colonialism.

The show was based on Shoaib’s research project, and most of the titles were taken from “Farang-e-Asfia,” a text that provides a fascinating glimpse into the lexicon of the era. He channelizes his extensive research by drawing from the source and underscoring how language continues to shape our perceptions of ourselves and our cultural heritage.

Shoaib Mahmood is a graduate of the National College of Arts (NCA), Lahore, and received his foundational training in the Mughal miniature tradition. With time, his practice has steadily evolved to engage with more conceptual and socially reflective themes. His latest body of work, The Brown Sahib, is a strong example of this thoughtful blend of technique, satire, and storytelling, standing out for its careful craftsmanship and strong sense of art historical awareness. For The Brown Sahib, Shoaib paints with gouache and 24-karat gold leaf on wasli—a fragile, handmade paper traditionally used in Mughal manuscripts—reflecting a patient, ritualized process rooted in centuries-old visual languages of Mughal and Persian styles. Shoaib Mahmood uses the same deep-rooted visual vocabulary to imaginatively address contemporary questions of identity, history, and language in postcolonial South Asia and how even after over eight centuries, the shadows of the British Raj continue to cast shadows on our sensibilities and societies at large.

In The Brown Sahib, Shoaib Mahmood’s compositions inscribed with colonial-era titles like White Mughal, Gora, Kala, Brown Sahib, Babu, and Jamadar in English/Roman words reclaim and recontextualize language that once reinforced colonial hierarchies and class aspiration. The result is a conceptual and painterly use of Roman/English calligraphy that explores how inherited language continues to shape postcolonial identity, self-perception, and cultural narrative.

Incorporation of the English language into his visual practice—an approach that remains largely uncharted in Pakistani fine art is a novel idea that Shoaib Mahmood has explored. While artists such as Shakir Ali, Anwar Jalal Shemza, and Iqbal Geoffrey engaged deeply with text, abstraction, and hybrid scripts, their works predominantly drew on Arabic, Urdu, or culturally syncretic forms. Shoaib Mahmood, by contrast, treats Roman/English script not merely as a linguistic or typographic device, but as a stylized, painterly element integral to the composition. His deliberate integration of colonial-era English terms into the traditional miniature format represents a thoughtful and possibly unprecedented shift, reframing the possibilities of calligraphy within a postcolonial, contemporary Pakistani context.

Writing for Dawn, art critic Quddus Mirza described The Brown Sahib as a “critique of our contemporary self,” noting how Shoaib Mahmood cleverly uses traditional portraiture and calligraphy to raise questions about social mobility, mimicry, and inherited identity. “The portraits are apparently in praise of power and aristocracy,” Mirza writes, “but these works, beyond their surface, reveal the psychology of oppression.” Shoaib Mahmood’s satire is subtle, embedded in the contrast between ornate visuals and politically charged titles.

Before The Brown Sahib, Shoaib Mahmood’s earlier work also reflected similar themes of history and belonging. He has consistently engaged with how language, power, and culture are inherited and reinterpreted. In April 2022, he presented “Same As That” at Canvas Art Gallery in Karachi. Reviewers from Dawn remarked on the show’s focus on cultural evolution, featuring delicate renderings of swords, headgear, and thrones against dark backdrops, suggesting “the evolution and transformation of religion and culture through time and technology.” His exhibition history includes notable solo shows such as “Break the Shape, Kill the Shine” (2015, Art Chowk Gallery, Karachi), “Tongue in Cheek” (2009, Drawing Room Gallery, Lahore), and “BETWIXT” (2008, Anant Art Gallery, New Delhi), alongside group exhibitions in Pakistan, India, Switzerland, and the UK. His participation in shows like “Preserving the Lost Era” (PNCA, 2025), “Open Letter” (O Art Space, 2023), and “Humanism: Flowering of the Being” (Asia House, London, 2023) has further cemented his reputation both nationally and internationally.

With The Brown Sahib, Shoaib Mahmood continues to build on a mature and considered practice. He proves that miniature painting, often seen as a classical or decorative form, can also be deeply contemporary. His work invites viewers to slow down, look closely, and reconsider the words and images that shape our cultural memory.

In a time when identity and history are constantly being redefined, Shoaib Mahmood’s work reminds us that the past isn’t just behind us; rather, it’s carried in our language, our institutions, and our everyday lives.