Acclaimed artist Basir Mahmood’s solo exhibition at Canvas Gallery, Karachi, opened with a contemplative dialogue on the role of art.

Basir Mahmood has always written in a language of gestures—sometimes choreographed, sometimes stumbled upon, always insistently human. His latest exhibition, In-Between Spaces of Energy and Consumption, does not shout nor narrate linearly. It waits. It arranges. It folds energy back into stillness, situating viewers in the uneasy pause where the hand has already moved, yet its trace lingers.

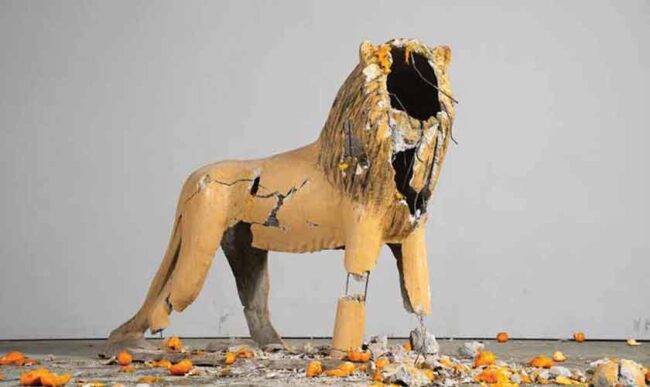

Earlier projects—Monument of Arrival and Return (2016), with its choreographies of migrant waiting, or Good Ended Happily (2016–21), with its dissonant Lollywood reenactments of geopolitical violence—were saturated with theatrical direction. By contrast, this show is hushed, reduced. Where once there were crowds and cinematic excess, now there are fragments: a broken lion, a fist of rice, a moon eclipsed by human hands.

The photographic series A Complete Meal (2025), nineteen variations of an arm outstretched with a clump of rice, epitomises Mahmood’s investment in delay. Each frame repeats a gesture both ordinary and monumental: the offering of food. As Henri Lefebvre reminds us, rhythm emerges wherever energy, place, and time intersect.¹ In Mahmood’s hands, rhythm becomes refusal—refusal to let sustenance be consumed in an instant, instead stretching the act into an archive of nourishment. The viewer lingers, and in that lingering, equality is glimpsed.

Likewise, Of the Same Taste (2025) stages confrontation between police and protestors, except their weapons are banana peels. The absurdist substitution derails the spectacle of violence, transforming aggression into a choreography of fragility. Jacques Rancière’s “distribution of the sensible ² is operative here: attention shifts from the clash to the absurdity of the objects exchanged. Political force lies not in the depiction of violence but in the redistribution of what counts as visible, sensible, or even edible.

In A Moon and a Half (2025), a diptych depicts an elder and a younger man alternately measuring one another with a tailor’s tape. The gesture is both intimate and transactional: a choreography of value, labour, and reciprocity. The tape, usually a tool of commerce, here becomes a mediator of dignity.

The symmetry of the two images destabilises hierarchy—who serves whom? Who measures, who is measured? Okwui Enwezor once described the “poetics of delay” as a refusal of spectacle.³ Mahmood inhabits that delay tenderly, allowing an exchange of glances and roles to eclipse the urgency of productivity. The labour of tailoring becomes a labour of recognition.

The fractured lion in Power Lion (2025) stands amid scattered oranges, its hollow chest and broken legs exposing the fragility of symbols. Once an emblem of sovereignty, it is now ruinous—what Fredric Jameson might call the allegorical ruin, where fragments speak louder than wholeness. The oranges complicate the allegory: vitality scattered around collapse, sweetness spilled beside decay.

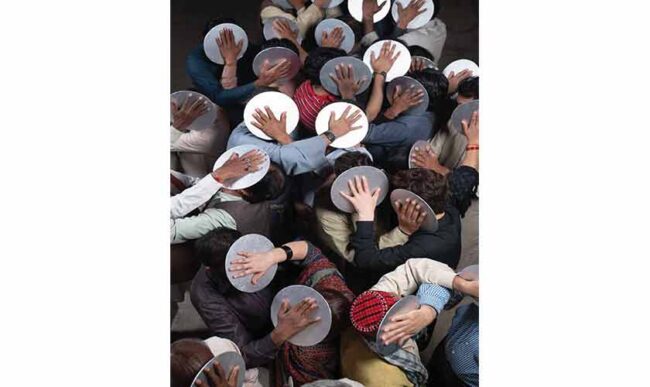

In Total Eclipse (2025), a crowd covers their faces with silver discs, pressing anonymity against their own skin. It is both absurd and terrifying—a lunar eclipse enacted through human erasure. Here, Mahmood stages conformity and concealment as a collective ritual, where individuality is occluded in favour of a strange synchrony. The eclipse, usually a cosmic alignment, becomes a metaphor for mass surveillance and social disappearance.

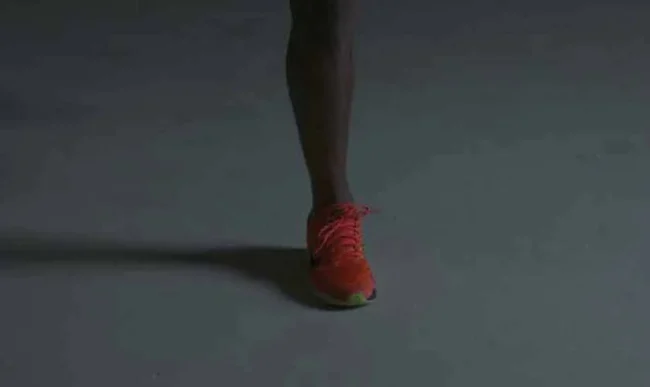

Re-presented from 2018, the video ‘In Authors Space of No Physical Actions’ shows a poised leg in a fluorescent trainer, suspended in expectation. For nine minutes, nothing happens—and yet everything does. Energy is caught not in motion but in anticipation, in the thickening of time. Mahmood’s refusal of climax is deliberate: a resistance to consumptive spectacle, a choreography of patience.

The diptych Anatomy of the Two I & II (2025) shows wrestlers locked in combat, their flesh punctuated by scattered oranges. Wrestling here is intimate rather than antagonistic; bodies entwine as much as they resist. The fruit transforms the scene into theatre, comedy, and tenderness at once. Mahmood stages the body as both site of contest and a site of care.

Hal Foster once described the “archival impulse” as a gathering of fragments not to complete the record but to expose its impossibility.⁴ Mahmood’s show embodies this: repeated images of rice, gestures of measuring, absurd substitutions of food for weapon. The gaps between works—silences, pauses, repetitions—become as resonant as the works themselves. In this sparseness, absence is testimony.

In-Between Spaces of Energy and Consumption is less an exhibition than an atmosphere, less narrative than rhythm. It asked viewers to enter suspension, to dwell in the poetics of delay. Against spectacle-driven art, Mahmood offered hesitation, tenderness, and absurdity as critical tools.

By folding food, labour, and gesture into allegories of power, he composes a quiet revolution. His works remind us that art is not only about what is shown but also about what is withheld—that silence can thunder, absence can speak, and consumption can reveal its hollow grace.

References

1. Henri Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life (London: Continuum, 2004).

2. Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004).

3. Okwui Enwezor, Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art (New York: International Center of Photography, 2008).

4. Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October 110 (Fall 2004): 3–22.

5. Canvas Gallery, Basir Mahmood: In-Between Spaces of Energy and Consumption (Exhibition Catalogue, 2025) .