A group exhibition at HAAM Gallery witnessed artists interpreting the theme feed through nuanced visual language, expanding its meaning through their works.

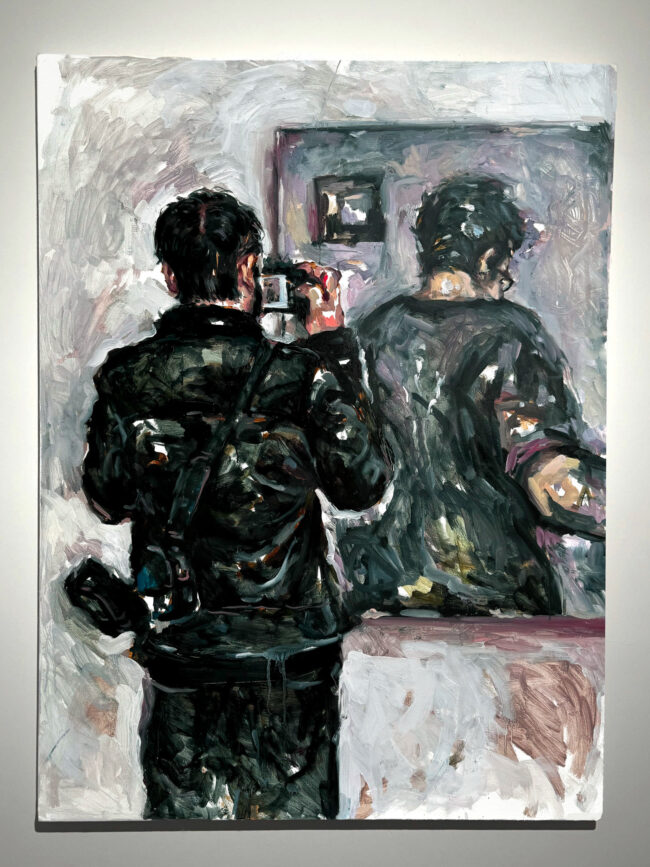

There’s something deliciously self-aware about naming an exhibition feed(/)me. It’s playful and deeply rooted in how we now consume culture. The title oscillates between two registers: the visceral cry to be sustained—“feed me”—and the endless, algorithmic scroll of the digital “feed.” It’s both intimate and structural, needy and critical. The proliferation of social media platforms has irrevocably fractured the traditional boundaries of the art world, transforming the museum into the timeline and the critic’s column into the comment section. Art now thrives in a condition of “Instagramism,” where work is often created not for contemplation in a quiet gallery, but for immediate, scroll-stopping visual impact—prioritizing shareability, high saturation, and clean graphic aesthetics over nuanced depth.

Curated by Ghazala Raees, in collaboration with Raees Khayal and HAAM Gallery, feed(/)me positions Instagram not as a distraction or dilution of art but as a legitimate, significant site of practice. Ghazala describes her impulse clearly: “Artists in Pakistan are already making powerful work for and through Instagram. This exhibition is about giving that space its due legitimacy, about saying: what you make for the feed is as real and as important as what you hang on the wall.”

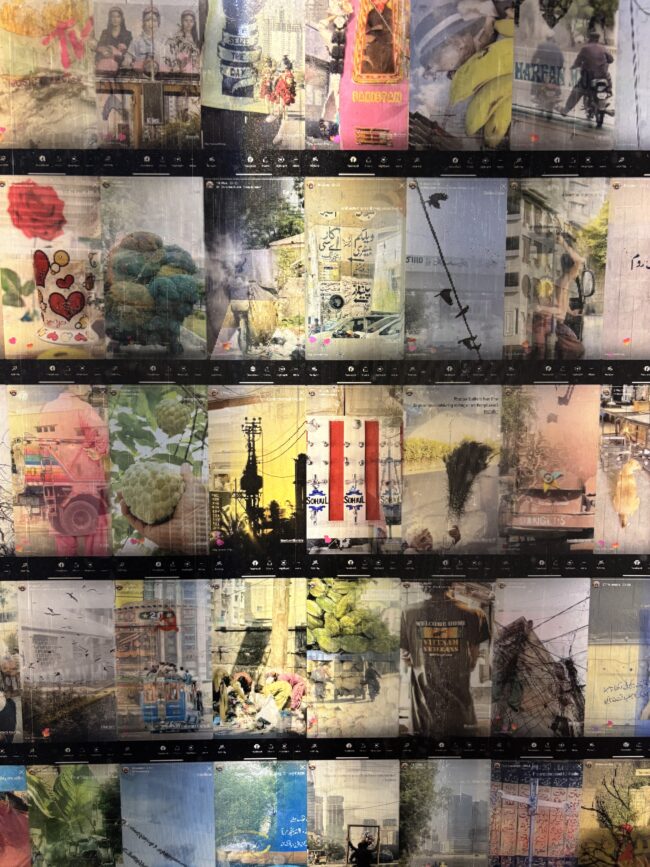

The now-ness of feed(/)me arrives at a moment when the boundaries of art are under pressure everywhere. If art history once belonged to museums and catalogues, today it unfolds on feeds, hashtags, and reels. The exhibition doesn’t simply acknowledge Instagram as a promotional tool; it treats it as a studio, a gallery, and an archive at the same time.

Works like Hania Batool’s The Hours Between (a digital Instagram reel) and Hoor Imad Sherpao’s The Casual Battle (which exists both as a watercolor-and-gold miniature and as a reel) exemplify this shift. They remind us that images don’t stop at the frame—they slide into feeds, pick up likes, and accrue meaning through circulation.

By bringing these works back into a gallery, feed(/)me complicates the loop: what happens when an Instagram reel is projected, staged, and experienced collectively? Does it gain gravity, or does it reveal that the digital space had already carried that weight all along?

Where many exhibitions treat social media as an afterthought, feed(/)me insists on its centrality. The curatorial vision is rooted in the urgency of the present: to understand contemporary art today, you must understand the logic of the scroll.

Compared with traditional shows, feed(/)me thrives on contradictions and contrasting elements. Paintings sit beside reels, delicate watercolors beside bricks stamped with Please Like Me. Instead of pristine silence, the exhibition hums with the restless rhythm of a feed.

Experiencing art in a gallery is very different from encountering it on Instagram. On the app, images are cropped, zoomed, or presented in grids, often accompanied by captions, hashtags, or music. feed(/)me leans into this tension by asking its thirteen participating artists to provide prompts on how their works should be shared online. Some request selfies taken with the piece, others suggest specific soundtracks to pair with their visuals. These gestures enrich the experience, transforming spectators into collaborators and reminding us that art today is as much about circulation as it is about display.

The show also refuses traditional hierarchies. Ayaz Jokhio’s still life, the work of an established senior artist, is placed alongside the reel of Hania Batool, a student. In doing so, feed(/)me echoes the flat logic of Instagram itself—where images scroll past one another without regard to age, pedigree, or seniority.

“The gallery had to feel like a scroll,” Ghazala explains. “Not everything will resolve neatly, but that’s the truth of how we encounter images now.”

Several artists in the exhibition push this logic further by engaging directly with the mechanics of social media. Safwan Sabzwari’s Please Like Me, staged on literal bricks, captures the desperate hunger for algorithmic approval, the irony of begging for engagement, and the heavy weight of digital dependence. The pieces are both satirical and poignant—solid, enduring objects that nevertheless embody the fleetingness of the scroll.

Mohsin Shafi’s Unfamous Pakistani Artists Association plays with the idea of recognition. By borrowing the look of official forms, the work makes fun of how much importance Instagram gives to followers and fame.

Sohail Zuberi’s #culturalbloodbank_karachi focuses on hashtags. His lenticular print changes as you move, reminding us that hashtags, too, can shift meaning, acting as places where culture and identity are constantly debated.

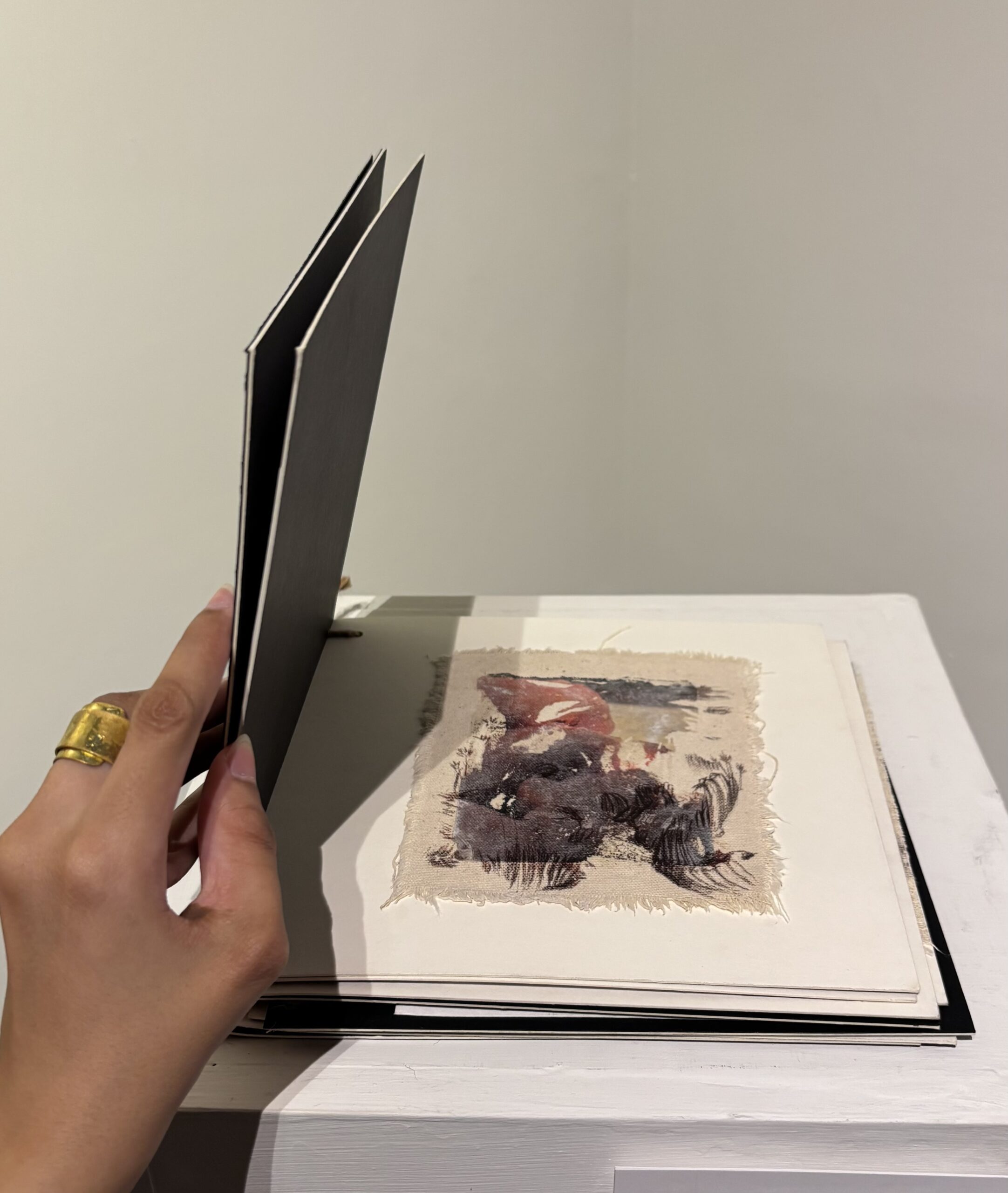

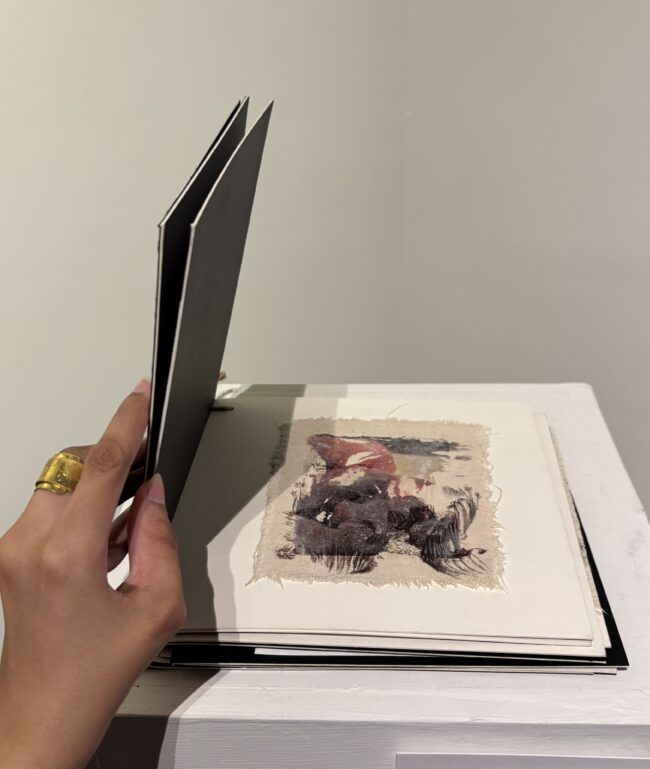

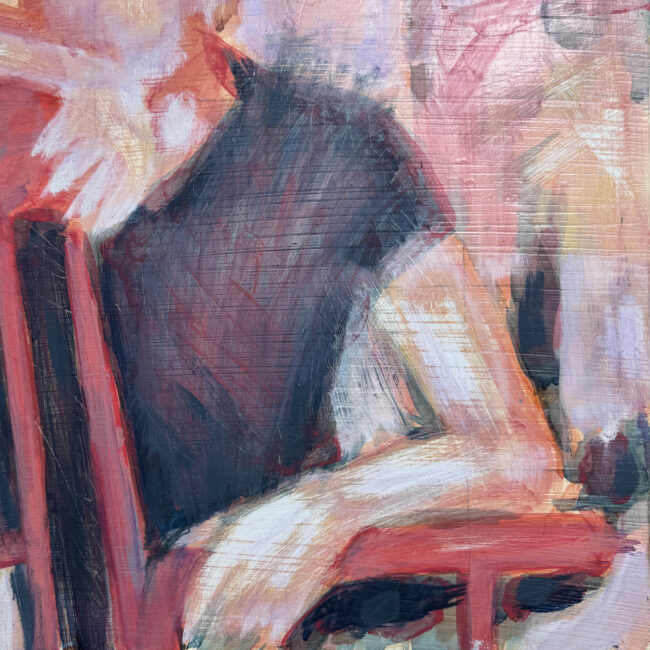

Aleezah Qayyum’s “pages” series, Ayaz Jokhio’s still life, and Faraz Aamer Khan’s watercolors are quieter works, but they draw viewers in through detail and care. They prove that in a world of constant scrolling, a single object can still hold attention.

Minaa Mohsin’s 12 Sarkari Gamlay develops this point further. She uses the everyday government flowerpot as her subject, turning it into a wooden sculpture. Simple yet striking, the work makes a common object feel important, asking the viewer to see it differently.

What sets feed(/)me apart is its curatorial honesty. Ghazala doesn’t present Instagram as a gimmick or a trendy add-on. Instead, she frames it as an inevitable extension of artistic practice today. “The question isn’t whether Instagram is good or bad for art,” she says. “The question is: what does it mean when the feed becomes the first place audiences encounter art? How does that change the work, the artist, and the viewer?”

In this sense, the exhibition functions as both an archive and a laboratory. It acknowledges the legitimacy of work created for digital circulation, while also testing what happens when those works are slowed down, recontextualized, and experienced collectively in a gallery.

Ultimately, feed(/)me doesn’t just document how art circulates online; it affirms Instagram as one of art’s main stages. A reel can be as carefully composed as an oil painting, a hashtag as culturally dense as a brushstroke.

By bringing together reels, memes, performances, and canvases under one roof, the exhibition doesn’t resolve the tension between digital and physical—it celebrates it. And in doing so, it marks a turning point: the feed is no longer just background noise; it’s a site of artistic production, legitimacy, and meaning.

The show leaves audiences with a provocation: when you scroll, you’re not merely consuming—you’re participating in the production of meaning. The feed doesn’t just display art; it feeds back into it. And by stepping into feed(/)me, we’re reminded that the act of looking, liking, and sharing is itself part of contemporary practice.

feed(/)me doesn’t just ask us to look—it asks us to scroll, to engage, to question. And in 2025, perhaps that is the truest mirror art can hold up to us. feed(/)me successfully navigates the increasingly blurred line between physical exhibition and digital spectacle, using Instagram as both a platform and a central artistic theme. In the gallery, the works—often brightly colored, highly graphic, and framed by stark light—feel simultaneously immediate and strangely familiar, as if plucked from a curated feed.

However, it’s the virtual dimension that defines the experience: the Instagram iteration isn’t a mere documentation, but an essential, coequal exhibit. Here, the artists embrace new-age modern visual aesthetics—from hyper-saturated filters and algorithmic sequencing to the use of glitch art and smooth, minimalist design—making the show intrinsically ephemeral and highly “sharable.” The work doesn’t just reference Instagram culture; it’s made of it, perfectly translating the platform’s instant gratification, stylized beauty, and inherent anxiety into a compelling, bifurcated viewing experience that feels utterly contemporary. One of the pleasures of feed(/)me is its refusal to reduce art to either/or. While the digital is foregrounded, the exhibition also insists on the stubborn presence of materiality.

Haroon Shuaib serves as a senior correspondent for ArtNow Pakistan, bringing nuanced insight and dedicated coverage to the country’s evolving art landscape.