In a conversation with Nusrat Khawaja, Noorjehan Bilgrami reminisced about memories, people and projects that have defined the rich contours of her life.

Noorjehan Bilgrami is a Pakistani art icon. Her creativity as an artist, designer, curator, and gallerist has redefined craft, education, and design in ways that are integral to the spirit of place. She brings studied observation and meticulous attention to detail to bear on all her endeavors. From the tiniest dot of paint on a canvas to a titanic project such as the Pakistan Pavilion at the Dubai Expo, an authentic representation of culture has become her hallmark and is evident in all that bears her touch.

The past is a repository of sensations and experiences for all of us. It is how we choose to activate certain memories that shape our choices in the present. Noorjehan was nine years old when she relocated to Karachi from Hyderabad, Deccan. Her affinity with color, form, and texture may be traced back to the Hyderabad of her childhood, well before her move to Karachi.

She recalls the scent of freshly picked motia flowers tied in her Nani’s mulmul dupatta; the gardens and streets of Hyderabad were infused with the heady aroma of the Maulsari (Mimusops elengi) flowers blooming on century-old trees. Home-made hibiscus sherbet glistened ruby-red through translucent glass.

Noorjehan’s color memory of her early years is dominated by red and shades of green. She remembers the rusty laterite soils of the Deccan, the boulders of Banjara Hills, the dark maroon lines of hopscotch grids etched in the monsoon-inundated earth. The Birbaboti (Red Velvet Mite) emerged in the rainy season, and children collected them in grass-lined matchboxes. Noorjehan’s affinity with a vivid and benign nature was established from early childhood and remains deeply rooted within her.

Besides nature, cultural practices going back to her childhood also play a foundational role in shaping her artistic worldview. Noorjehan recalls the varied sights and smells in Charminar Bazaar, Hyderabad’s historic market that was founded by Sultan Muhammad Quli Qutub Shah in 1591. Glass bangles sparkled on stands. The bazaar was replete with textiles, fine brocades and itar. Narrow lanes were lined with jewelers’ shops selling pearls, while the Nizam’s lustrous jewelry became the template for Kundan designs. This was Noorjehan’s past – enriched with scent, color and texture – that she has never stopped carrying within herself.

Noorjehan’s veneration of cultural traditions includes the appreciation of the ustad-shagird relationship. Mentors have played an important part in her personal development by imparting their learning to her and shaping her aesthetics, making her a link in their transmission of knowledge. Her thirst to learn is unquenchable and takes her to places and people from whom she can imbibe knowledge. She is a believer in the creative enigma of coincidence and its unique ability to connect the dots in life’s trajectory.

Noorjehan enrolled at the Karachi Grammar School. Her A-Level art teacher, the late Mrs Tahira Rafiq, was an early mentor who stood out for her innovative teaching methods. She took her students to outdoor venues to sketch from life. Empress Market was a place of choice for student visits; amidst the buzz of energy, sat Kohli women grinding masalas, reminiscent of the banjara gypsies in Charminar Bazar.

Noorjehan attended the Lahore National College of Arts (NCA) for two years. Shakir Ali was the principal, newly returned from Europe, with fresh ideas on modernism. Other luminaries who acted as mentors at the NCA included Khalid Iqbal, Colin David, Saeed Akhtar, Mian Salahuddin, and Ahmed Khan.

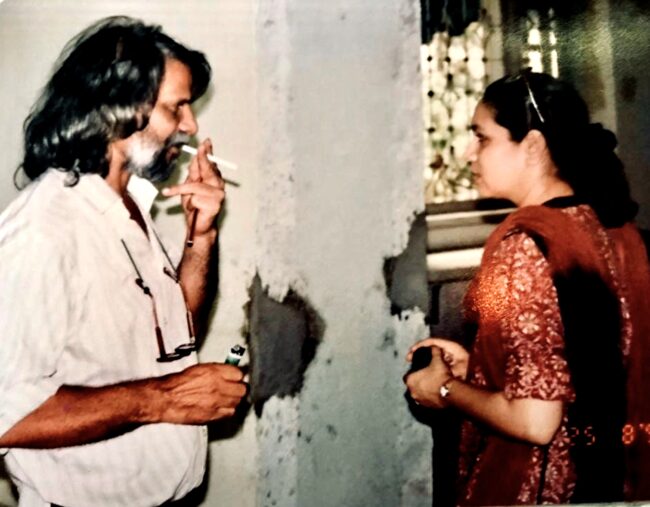

She then transferred to Karachi and enrolled at the Central Institute of Arts and Crafts (CIAC), which was located within the Arts Council of Karachi. It was a vibrant place, brimming with the energy of teachers and students who loved creating and discussing art. Syed Ali Imam had relocated to Karachi from London in 1966 and was the principal of the CIAC until he opened Indus Gallery in his PECHS home in 1971. Bashir Mirza, who had opened The Gallery – the first commercial art gallery in Karachi – came to teach at the CIAC. Ahmed Parvez, Sadequain, F N Souza, and M F Husain were frequent visitors.

Noorjehan’s development as an artist coincided with her discovery of indigenous crafts. Craft is integral to the arts tradition of the subcontinent. Noorjehan dismisses the dichotomy between art and craft that was introduced by the British colonialists through a binary perspective.

She venerates the traditional methodologies of art/craft production that relied on a collaborative system of work under a Ustad who often ran his own atelier.

An important mentor in adulthood, who imparted her knowledge on textiles to Noorjehan, was Mrs Feroz Nana. Ethereally attired in a white gharara with wrists adorned by bangles, and kajal in her eyes, Mrs Nana would open camphorwood chests in which she stored her collection of textiles and discuss the style and provenance of the treasured fabrics with Noorjehan, who eagerly soaked up the information. The instruction went beyond the physical appraisal of fabric and into the metaphysical dimension as Mrs Nana spoke of the circle as the foundational motif for design and life.

Noorjehan’s experiments with wooden blocks for dyeing fabric began in 1975 and burgeoned into a cottage industry that made traditional block-dyed clothing a fashion statement. She frequented Lee Market and Khajoor Bazar, the two sources where traditional textiles could be bought.

As a child, Noorjehan was taught traditional skills of cutting fabric, sewing and embroidery. She learnt to identify fabric textures when being taught to sew by her mother (a skill she values greatly and is now passing on to her granddaughter). One may extract an analogy from the discipline of sewing, where one neat stitch follows the other, and apply it to her methodology of work, where she builds projects with similar meticulous progression.

Noorjehan operated her studio and Koel boutique from her home for several years until the formal opening of the Koel Atelier in 1995. The name ‘Koel’ was chosen by Noorjehan for its evocation of the monsoon season and the gentle call of the koel bird, which lived in the Cheeku tree that grew in her garden. The iconic koel logo was made by her classmate Imran Mir. To date, the exhibitions and programs overseen by Noorjehan in the gallery space number in the hundreds.

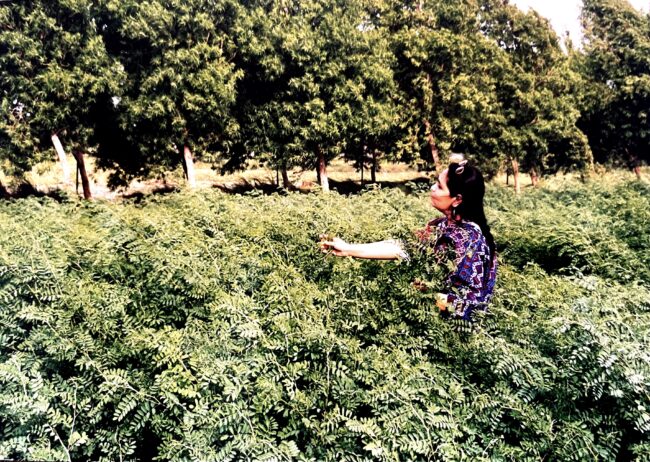

In 1980, shortly after Noorjehan had started her block print business, she attended a workshop in New Delhi on natural dyes given by the maestro V K Chandramouli, whose compendium ‘Sources of Natural Dyes in India’ is a classic. The in-depth focus on plant-based dyes drew Noorjehan towards indigo production. She successfully undertook a pilot project in Miani Forest, under the aegis of the Forest Department, for four years (with her friend Masuma Lotia) to cultivate the Indigofera tinctoria plant that produces the legendary blue indigo dye.

If red and green were the dominant colors of childhood remembrances, blue and madder became the markers of her journey with fabric dyes, particularly through the medium of Ajrak.

Ajrak – unique to Sindh and replete with symbolic motifs – was a much used but under represented textile. Noorjehan did a thorough study of the material and visited ‘ajrak-making’ villages in Sindh. Her research culminated in the book ‘Sindh jo Ajrak’ in 1990. This was the first of several books she has authored on craft traditions.

Mr. Ali Ahmed Brohi became her invaluable gateway to the villages in Sindh. He also introduced her to Dr Harchand Rai Lakhani in Umerkot, the humanitarian physician to whom women would come for treatment and pay by giving sewn garments instead of money.

The lines of transmission and cultural encounters extended through the length of Pakistan and far beyond to Sri Lanka and Japan.

The timeliness of coincidence is a recurring phenomenon in Noorjehan’s life. They point to directions and people who become part of Noorjehan’s creative repertoire. A case in point is her discovery of Sri Lankan architect Chelvadurai Anjalendaran’s design for the SOS Children’s Villages. She learnt about him while browsing through a magazine in the dentist’s waiting room. She was so captivated by his naturalistic style of mingling garden and house that she decided she had to meet him. Her assiduous search led her to the SOS Children’s Village in Piliyandala. Her meeting with Anjalendaran was one of several deep connections she established with illustrious Sri Lankans such as Geoffrey Bawa and Barbara Sansoni.

Noorjehan’s quests are precursors to knowledge repositories that inform her visionary acumen for project development. A legacy project initiated by Noorjehan is the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture. Noorjehan picked up on the pulse of heightened art activity in Karachi and sensed that an art school in the metropolis would be viable. It will play an essential role in decolonizing those approaches to art that were instituted by British administrators. She and her husband, architect Akeel Bilgrami, along with a few select artists and architect friends, became the founders of the now flourishing school, which opened in 1991.

The Dubai Expo 2020, for which she was selected as Principal Curator for the Pakistan Pavilion, was a mega-project of a different nature. The Pavilion won the Silver Award for interior design (second out of 192 participating countries, with Japan winning the first prize) and led to Noorjehan being awarded a Tamgha-e-Imtiaz.

Her most recent international curatorship has been the Pakistan Pavilion at the Osaka Expo 2025. This is an intimate Pavilion (very different in scale and character from the Dubai Expo) for which Noorjehan designed an immersive healing garden made of pink Himalayan rock salt, which is unique to Pakistan.

When quizzed on the secret to her success in achieving her vision for projects, Noorjehan reveals that she prioritizes personality above skill set for people she chooses for her team. She says it is important for the project’s success if energy, curiosity and hard work cohere.

A complete chronology of Noorjehan’s life would require a book to be written. Indeed, her impressive CV runs into many pages. She has set the highest bar for professional achievement. She has traversed space and time to create webs of cohesiveness between the past, the present, and the future. She has valued what is our own and created a legacy of appreciation that transcends the pettiness of ego or politics. This is what it means to be Noorjehan Bilgrami.