Haroon Shuaib offers a critical examination of internationally acclaimed artist Waqas Khan’s work, drawing insights from a close visit to his studio.

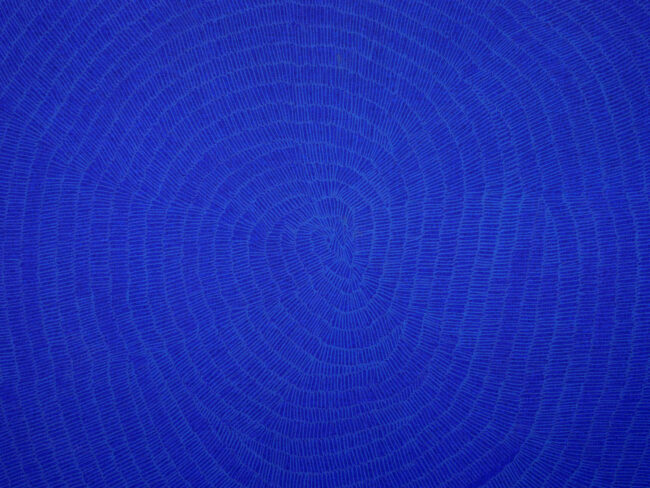

To define Waqas Khan’s art as abstract may be convenient but is a gross minimization. Within the hushed sanctum of his Lahore studio, I stood before a vast canvas awash in an impossible azure, bordered by a constellation of meticulously placed motes. I experienced an instinctive epiphany moment. Khan’s art was having the same effect on me as the earliest Neanderthals must’ve experienced staring at the first ever twig-stroke, bone-scratch, or coal-kiss on stone – as if all the mysteries contained in this incredible universe had come undone. It was before the tyranny of form, shape, and color; let alone the intellectual métier to deconstruct and explore beyond. It was like the first step towards unveiling the cosmic DNA. It was serendipity.

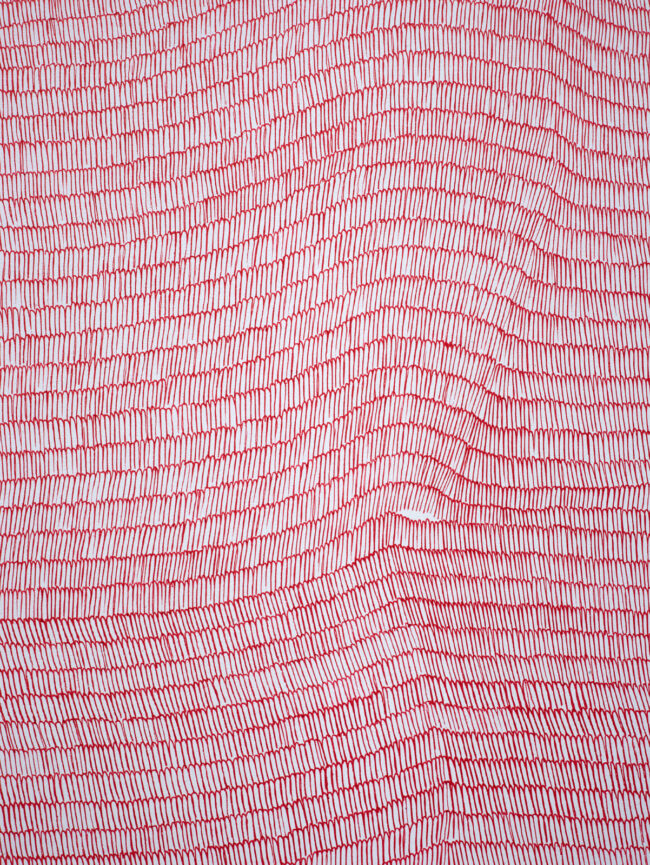

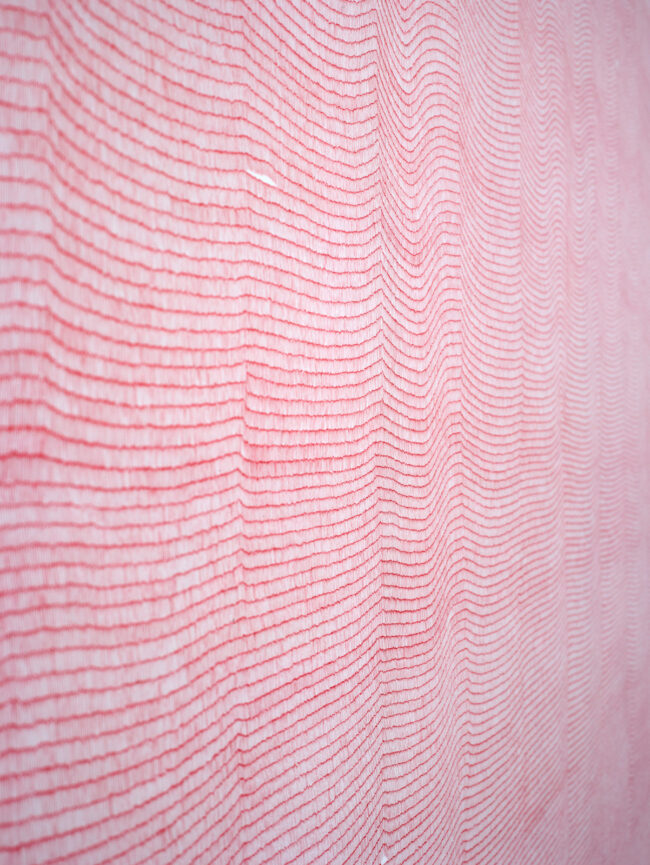

Born in Akhtar Abad, Okara, Khan started his sojourn with art in the fires of the NCA’s printmaking forge. His art, a language untamed, eluded even his grasp and remained a riddle whispered beyond the ken of the most seasoned seers of the art world. During his time at NCA, Khan’s experiments with sculpture, architecture, miniature, weaving, and dance contributed to this. To intellectualize Khan’s artistry within the esoteric veils of Sufic art would be to elevate it to an austere, inaccessible summit. His spirit, steeped in a profound humility, recoils from such lofty charades. To merely label his meticulous craft as pointillism would be to diminish the sacred weight of each infinitesimal mark, each speck of ink that Khan, in tireless devotion, imprints upon his canvases, heedless of any grand, unified design. Each laceration, each delicate incision his pen inflicts on a work, hour after hour and night after night, stands as a microcosm, a self-contained world of meaning. Even the most assiduous pursuit of parallels within the narratives of tribal art would prove a barren endeavor. Khan’s art possesses a profound, resonant depth, a quiet gravity that transcends facile categorization, demanding to be felt, not merely understood. Salima Hashmi wrote about this in an article published in 2017: “Khan’s work invites the onlooker into a world of solitude. It insists that the viewer become a participant, engaging with the myriad journeys of the marks and dots which can turn inwards or just as easily seep outwards in trails across silent spaces.”

Khan, with a wry, self-effacing smile, confesses that his reason for joining NCA was less a calculated pursuit of artistic mastery and more for its liberal spirit. Within those hallowed halls, however, bloomed an unlikely craft: a minimalist lexicon, a meticulous dance of a thousand dots and lines, often less than a centimeter each. His was a cryptic yet intuitive script, bewildering all established art definitions as much as the artist himself. The loom of Khan’s becoming spun finer threads with each drawn breath, each silent, stretched moment before the vast, unyielding primarily monochromatic canvases. He weaved not with silk or wool, but with each whisper of his touch, crafting webs of worlds within worlds, nucleotides dancing on a macrocosm’s skin, arranged in schemes such as nature displays in the spirals of a seashells, tessellations of a honeycomb, and Fibonacci sequences of sunflower seeds. The meditative practice of perfected creativity now ascends Khan, unwittingly, to planes beyond his conscious navigation. His plotting on canvases, now almost miraculously, aligns with geometries that whisper perfection.

A very loaded citation of Khan’s Hidden in Stratum, displayed at the Toronto Biennial 2022, stated: “Waqas’ work cannot be compartmentalized within Eastern or Western epistemological frameworks—it is neither indebted to miniature painting nor minimalist abstraction but, rather, moves somewhere in between… Like a biological organism grown from a single cell, the marks in Waqas’ works coalesce into larger forms. They appear as particles that are at once individual and part of a greater whole. These networks reflect the complex relations of individuals within a collective, of kinships that do not reduce differentiations but are rather strengthened by interrelations across differences”

Khan’s works are part of the permanent collections of prestigious institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Manchester Museum, the Kiran Nadar Museum, Fundación Calosa –Mexico, and Deutsche Bank, among many others. He has displayed extensively across the world including at Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA), Saudi Arabia Museum of Contemporary Art (SAMoCA), National Museum of Sculpture in Spain, Galerie Krinzinger in Vienna Austria, Pera Museum in Turkey, the Foundation Boghossian – Villa Empain in Belgium, Aicon Gallery New York, and at Dhaka Art Summit. Besides the 2022 Toronto Biennale, Khan has also been part of the Asia NOW Paris, Frieze London, Art Basel Hong Kong, Asia Pacific Triennale 9 at Queensland, 2018 Lahore Biennale, 57th Biennale di Venezia Italy in 2017 and many more.

Khan’s use of a universal creative dialect makes his art relevant beyond the confines of time, space, and culture. His art, a living pulse, echoes the very cadence of existence. It was, perhaps, this primal resonance that compelled him to silence music, once a companion, in his Lahore studio. Over time, music had become a distraction to the sacred ritual of creation. He sought instead the profound hush, the stillpoint where pigment became strata, and his hand, a delicate excavator, unearthing hidden truths with microscopic precision. Each scrape, each subtle shift in pressure, a whispered dialogue with the layered past of a planetary heritage. A symphony of solitude, where the artist’s heartbeat became the metronome for his masterpiece.

Jonathan John writes for the Guardian on art and has served on the jury for the Turner prize. He interviewed Khan during the latter’s visit to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. In his article, John notes Khan’s ‘brilliantly enigmatic blue canvases’ with ‘white unreadable script – like ghost calligraphy – and interlaced cosmic circles’. “This is art to transport you. To his Mughal heritage, Khan has added the majesty of Rothko. Muslim history merges with American modernism. Lahore meets Manhattan. Khan’s work is uplifting and entrancing. He is an artist of peace in a world at war.” John writes.

Waqas Khan has also co-founded ‘Nathuu’ (www.nathuu.com) with his wife, Bushra Waqas Khan. Nathuu is a social project that brings joy through art education to children across Pakistan, especially those from difficult socio-economic conditions, and helps them unlock their creative potential – rediscover the missing cosmic DNA that made our earliest ancestor break free from the dreariness around and make that first cave drawing. Like all serendipitous experiences, Waqas Khan’s echoes of the same primeval scratches, on canvas after canvas, drift like a phantom ship upon the vast, borderless pandemonium, where the currents of local taste and the reefs of prejudice hold no sway.