When I visit art exhibitions I go in with a rule: I don’t look at the titles of the works. Though titles can be an enriching detail that adds depth and context to the art at hand, however, the title takes away something from art. Not something, a lot. The focus of a title risks brushing off the many layers of perception and, for some works, the multisensory layers form the entire practice. Thus, my rule to forget titles, for a while, came into existence.

For Rabeya Jalil’s recent solo show, this rule was all the more relevant. For a practice that is richly rooted in instincts and embodiment, looking at the titles for a superficial understanding doesn’t do the work justice.“Lines and Language”, a solo showcase by Rabeya Jalil, opened at Canvas Gallery, Karachi on November 25th with 20 works of acrylics on canvas. The artist has been engaged with practice, theory and education for a course of 20 years and currently heads Painting at National College of Arts, Lahore. I met her for the first time in an educational setting, I had been enamored with her practice for some years prior.

However, this review is not only a hymn that celebrates this solo show but also a lament for the separation of instincts from art and an appeal to return to our imagination and innate knowledge systems. “The work is a cross-over between representation and abstraction,” says the artist in her statement. “Using intuition, chance and repetition as strategies for making, I reflect on the subliminal, latent structures that determine hand gestures while making marks on a two-dimensional surface.”Once you distance yourself from the titles, you bring your full attention to the work and the balance between representation and abstraction. Unless, you go to the artist and talk to her. With this particular artist, this will be a failed attempt because she will inquire if you’ve seen the work and, if not, she will redirect you towards it.

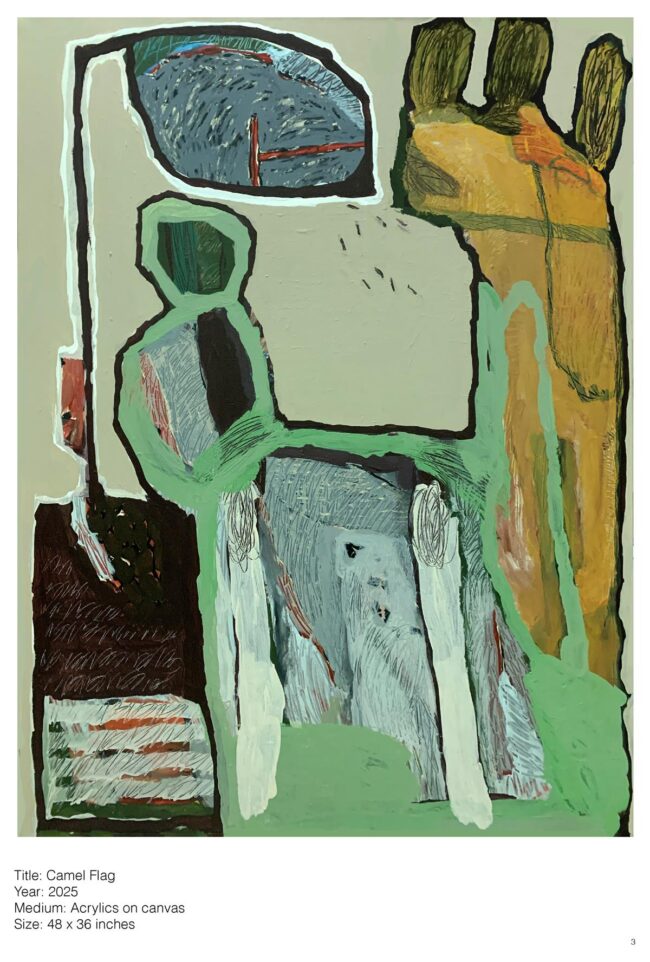

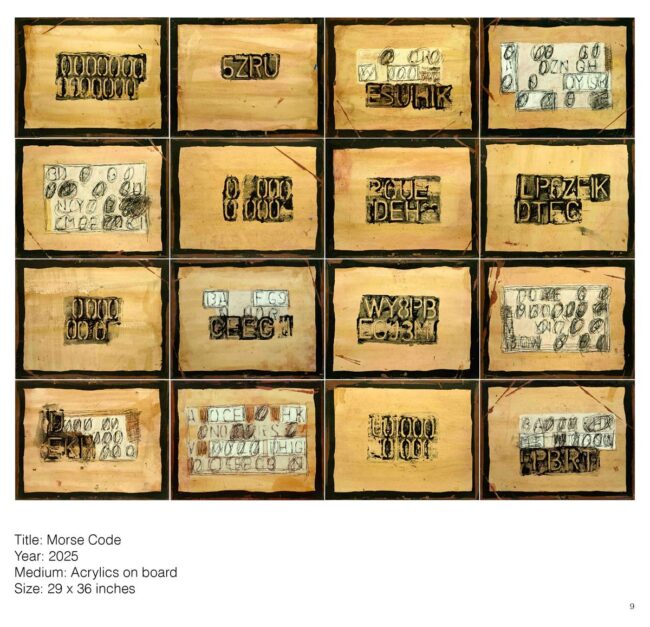

The paintings, at the first glance, look like an explosion; of thoughts, experiences, time and places. Somewhere the explosions were more silent, though the silent language can actually be more intense as a sensory stimulus. Jalil brought a diversified flavour of lines; from bold, quick and expressive, to clean, minimal and contour-like. Similar were the experiments with colour and form. High contrast and bold shapes were paired together in works, capturing some loud inner voice struggling to escape and break free from a metaphysical cage. Some works echoed the layering of activist posters throughout the city’s walls, reducing the details through the use of gestural colour and some held scribbles and erased textual details like handwritten notes, phone numbers and confessions of love on the walls of public monuments or bus stations. Other works were more muted in tone, but not in sensory detail.

The washes of monochromatic colour were overlaid with fine, delicate lines and etchings. Each mark felt like a slight change in the wind as seasons change from autumn to winter; almost like a whisper as soon as you’re about to fall into slumber and you hear a distant voice call your name. The art demanded to be seen closely.Now if we notice the titles, if we must, we see a secondary layer in Jalil’s practice: the mention of the everyday. Lucy Lippard in her text on art and prehistory, labels this as an essential function of art, “by looking back to times and places where art was inseparable from life”. But these are not just any times and places.

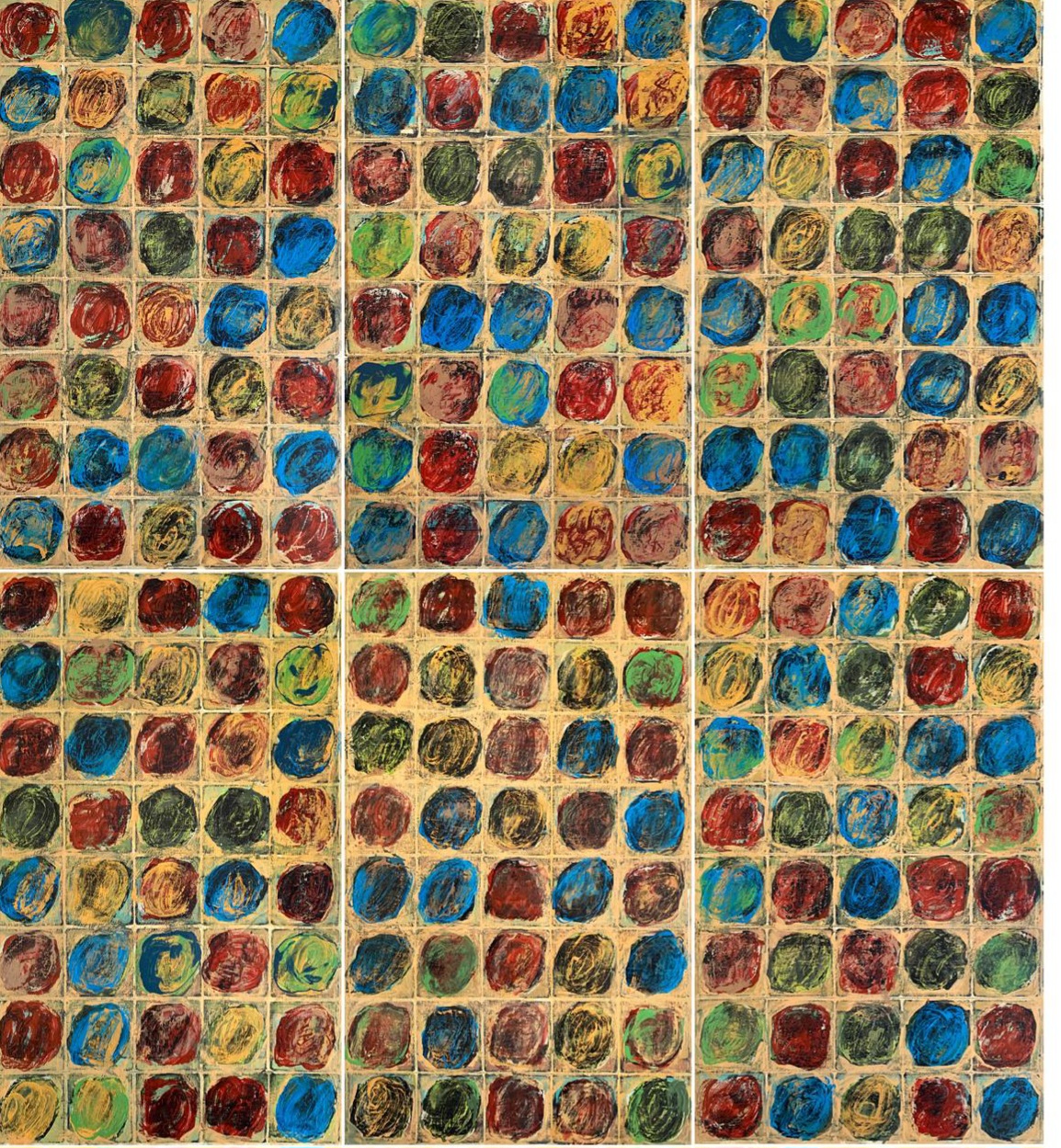

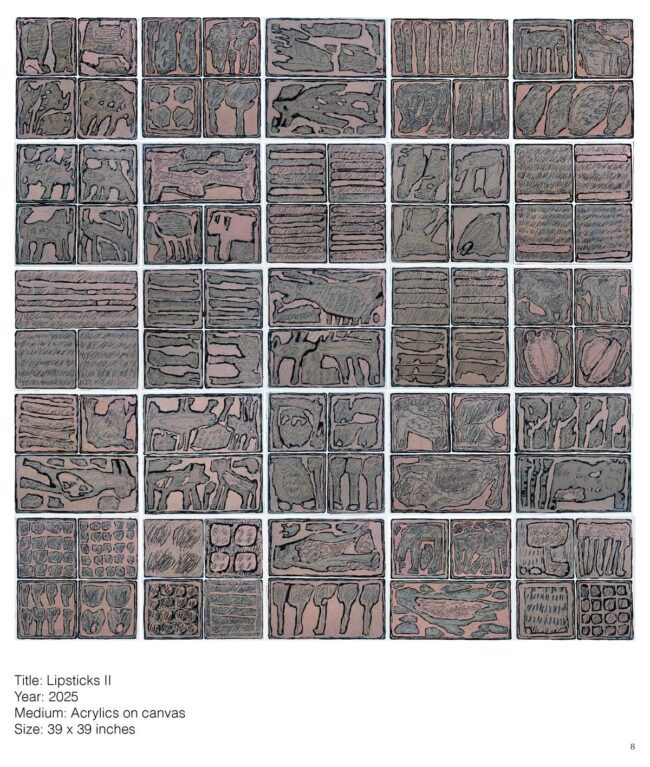

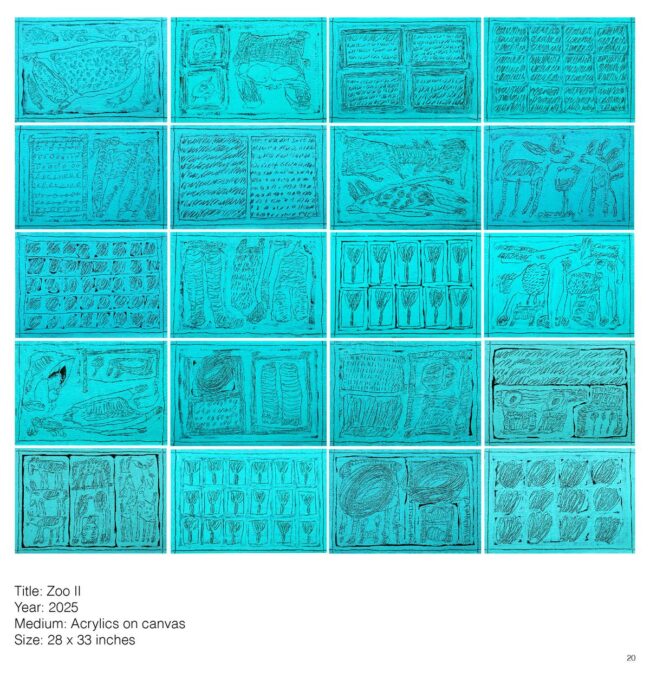

Some are specific references to physical spaces like “Zoo II”, “Rabbit Hole”, “Rain Forest”; bringing the natural environment quite directly and plainly. Garden is an aerial map of a garden. There is hushed satire and sarcasm hidden in this plain use of language and literal translations. Some are objects like “Lipstick II” and actions like “Animal Play”. “Colour Wheel” employs repetition and circular forms and reminds me of untitled drawings by Eva Hesse created in 1966-67.

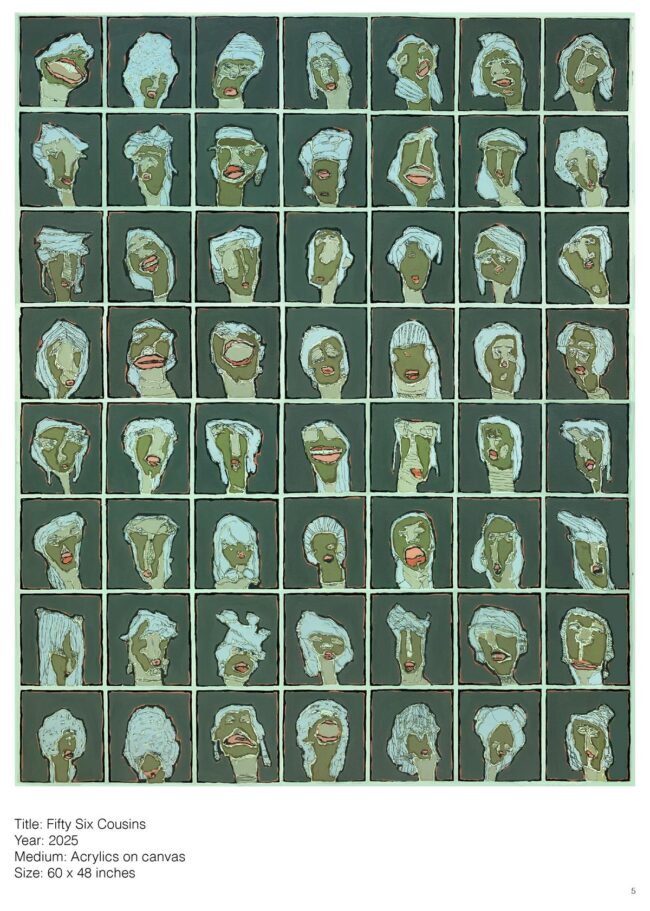

This artist, like Jalil, had an instinctive and gesture-focused practice and she often used aerial layouts and repetition as strategies of mark-making. “Army” and “Fifty Six Cousins” feature a repetitive approach too and the inclusion of portraiture makes these two paintings visually the most distinct, leaning towards representation more than abstraction.

I remember seeing Jalil’s portraits in her last solo at Canvas Gallery, “Between Meaning and Making”, 2023 and I felt they resembled the language of communication design; storyboards and comic book panels. But now that I look at these contour faces I think of simplicity, movement and the techniques used in primitive art, where time was of the essence and survival was at stake, rendering realism in form unnecessary.At this point, looking through Jalil’s paintings and the titles, searching for hints, clues and answers and finding connections and sense feels like you’re playing a game of riddles or fixing a puzzle. The work, then, reminds us of play and curiosity, both of which are lost concepts in the everyday life of an urban city. In finding my own connections, I noticed a work titled “Lipstick II” but there is no Lipstick I. It makes you wonder if the work was made with a lipstick or commemorates a certain lipstick in the artist’s life; maybe the lost lipstick I? The artist leaves nudges and missing links and urges us, the viewers, to absorb, question, feel and connect things together. The artist wants us to speculate and imagine. And lines have been used to do this very task for ages; to connect visible things. We learned as kids to connect lines to dots and that is how we learned the alphabet and developed the sense of a language. The stars were connected to create constellations and they became a map for travelers to navigate the great seas and for others they became faith. Something so grand, a mediator between people and their plans, starts from something very simple; two far off ideas connected with a line, sometimes directly and straight and other times broken or curved or spiraling.

Speculation and imagination have been at the very beginnings of languages, maps and meaning-making.When you focus all of yourself; your emotional and physical attention to these minute details and connections, you feel far removed from the outcome. You see the process over the product. The commodification of art has been subdued by the social and historical relevance. A social perspective on art-making seems to come from Jalil’s experience with teaching and educational projects. Only a committed artist-educator would be as sensitive about social inclusion within art and be as brave to take bold risks around low art and instincts. As Lucy Lippard highlights, without social exchanges, “culture remains simply one more manipulable commodity in a market society where even ideas and the deepest expressions of human emotion are absorbed and controlled.” Lucy Lippard speaks of the commodified art market when she says this and Jalil’s solo questions these exact notions. Artists have been working on the distinctions and debates surrounding high art and low art as well as art versus craft.

These debates are rooted in either the culture of commodity or class systems. Amidst this dynamic, Jalil’s practice positions itself as a contradiction to formal training, as highlighted in her artist statement that the work “critiques academically trained aesthetics and formal art education to understand cultures of authenticity in a visual language system”.Though I don’t think formal training induces pretense in artists, maybe the demand to produce, showcase and sell work does. Or maybe believing that trained aesthetics are better than the work of primitive artists and craftsmen, who used the natural environment, play or daily lives as inspiration. Modernism and technology may have played a role in stripping us from the imaginative and innate knowledge system. We have given up our decoding systems to external mechanisms. It starts with something as simple as looking at the title of an artwork or reading the artist statement to understand work. And escalates as far as asking AI to decipher art and literature for us. Everytime we try too hard and too far to make sense, we outsource our imagination and speculative abilities. In doing so, we forgo our authenticity behind the production of art and fall into the commodity culture. Though many artists, especially those working in analog mediums of drawing and painting, seem to be functioning perfectly along these social and capitalist margins, this exhibition sees otherwise. It reminds us of the social roots of art, gestures of the body and the inherent ways of meaning-making; producing art like Jalil’s is no less than a revolt in the present age.

ReferencesLippard, Lucy R. Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory. Pantheon Books, 1983.De Zegher, Catherine, editor. Eva Hesse Drawing. Yale University Press; The Drawing Center, 2006.

Jabeen Qadri is a multidisciplinary artist and writer based in Karachi