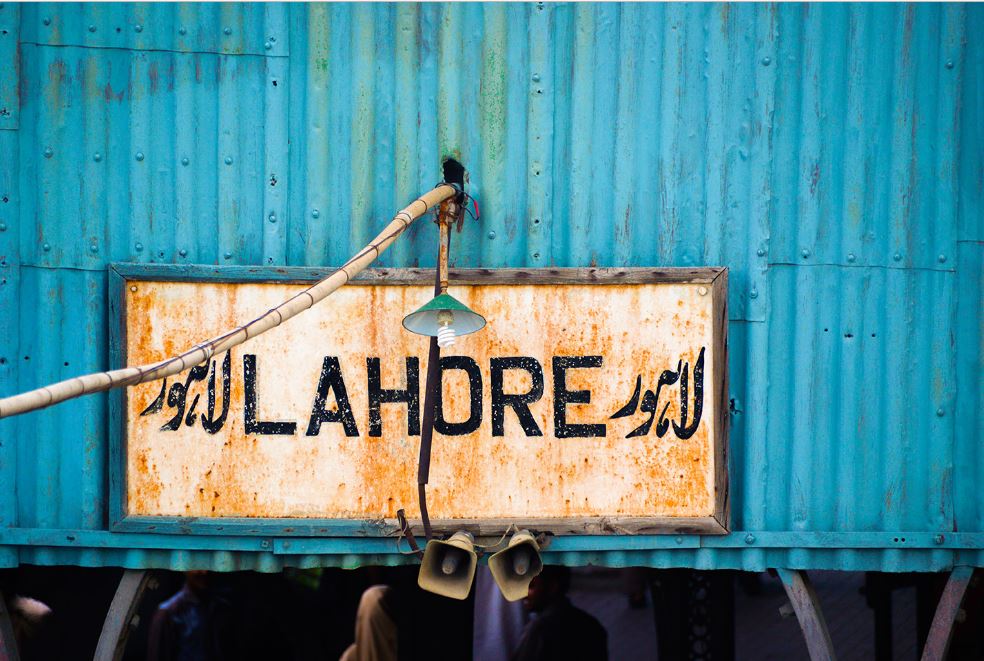

Since its founding, the Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF) has been one of the clearest catalysts for reconfiguring how contemporary art is produced, circulated, and experienced in Pakistan. What began as an effort to stage large-scale exhibitions outside the few long-standing institutions has, over successive editions, turned into a multi-pronged project: building cultural infrastructure, animating public and heritage sites as venues for site-specific practice, and closing gaps between artists, institutions, and general audiences. Together, these moves have shifted contemporary art away from being a niche, institution-bound practice and toward a more civic, city-wide phenomenon.

One of LBF’s most tangible impacts is infrastructural. The Foundation has not only produced three major biennales, with LB01 in 2018 and subsequent editions in 2020 and 2024, but has layered that programming with research, publications, residencies, workshops, and digital platforms that endure between editions. These activities create ongoing capacity, curatorial networks, administrative know-how, conservation and installation experience, and documented research that other organizations and artists can draw on. In practical terms, LBF has modeled how to commission, fund, and deliver large public-facing exhibitions in Pakistan, knowledge that did not exist on this scale before and that other groups now replicate or build upon.

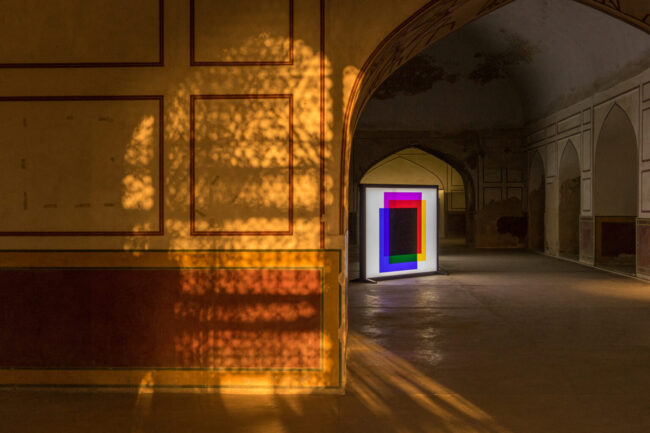

Closely related is how LBF has transformed public and heritage spaces into active sites of contemporary art. Rather than concentrating work inside a gallery box, the Biennale has staged site-specific commissions across Lahore; within the Walled City, at the Lahore Fort and Shalimar Gardens, in civic squares and disused buildings amongst other sites. Thus, turning the city into a kind of open-air museum during each edition. This relocation does not merely place work in public, it forces artworks to engage with layered histories, everyday users of those spaces, and the rhythms of urban life, producing artworks that are socially rooted and legible to non-specialist audiences. The effect is twofold in introducing people who might never enter a gallery to encounter contemporary practice to prompting artists to produce work that directly addresses public concerns like heritage, ecology, migration, and labor. Going beyond the existence of art that circulates only within elite circuits.

The Foundation has also made explicit moves to bridge institutional gaps. LBF’s programming deliberately links international curators and artists with local partners, museums, municipal bodies, banks, heritage authorities, and artist collectives, creating formal and informal partnerships that extend capacity beyond the Biennale itself. Recent MoUs and collaborations with civic heritage authorities and financial institutions, for example, signal new models for public–private cultural partnerships in Pakistan. These agreements help secure sites, funding, and logistical support for large outdoor projects, things previous generations of artists often had to improvise on or go without. The institutional legitimacy this generates is significant. It makes the case that contemporary art is a civic asset rather than a marginal pastime.

Accessibility, both cultural and geographic, has been central to LBF’s stated mission and visible practice. By taking commissions into neighborhoods, providing workshops, learning programs, and developing online resources such as a virtual museum and publicly accessible research outputs, the Foundation has broadened the pool of who can participate in contemporary art discourse. Educational outreach, artist workshops, and public programming demystify curatorial processes and offer paths for emerging practitioners and students to engage with directly. This recruitment of new participants is a long-term cultural investment. It enlarges the pool of makers, audiences, and cultural workers who will sustain Pakistan’s art ecology in the decades to come.

Perhaps the most consequential effect, and hardest to quantify, has been the shift in how audiences and artists imagine the role of art in civic life. By presenting ambitious, topical projects in familiar urban places, LBF has reframed contemporary art as a public conversation about environment, heritage, and social futures, rather than as an inward-looking or academic exercise. Critics and international observers credit the Biennale with lending Lahore a renewed cultural visibility, attracting international curators and attention while simultaneously prompting local experimentation, artist-run shows, pop-ups, and interventions across the city. The result is an ecosystem that is more porous, more collaborative, and more likely to sustain local initiatives beyond the scale of any single exhibition.

The Lahore Biennale Foundation has acted as an engine for infrastructural development, a catalyst for rethinking public space as a site of artistic encounter, and a broker between local practices and global curatorial networks. Its work has demystified contemporary art for wider publics and shown how cultural projects can be embedded into the civic fabric. The longer-term measure of that impact will be how durable the institutional relationships, educational pipelines, and public-facing practices it seeded become, but already LBF has shifted expectations about what art in Pakistan can be and whom it can be for.

LBF’s inaugural edition, LB01 in 2018, staged site-specific projects across Bagh-e-Jinnah, Shahi Hammam and other sites in Lahore. The first edition established LBF’s approach of working with public and heritage sites, and of layering public programs, forums, youth engagement and talks onto exhibitions. LB02 in 2020, curated by Hoor Al Qasimi and titled Between the Sun and the Moon, amplified participation from the Global South and presented work across multiple civic and heritage sites. The edition consolidated the Foundation’s commissioning model, publications, and public programming. The third edition, Of Mountains and Sea (LB03, 2024), under John Tain’s curatorial leadership, expanded site choices. With continued commissioning of international artists and historic sites such as the YMCA and other civic venues, sustained public engagement and cross-regional exchange were emphasized. The edition further refined LBF’s curatorial networks and institutional partnerships.

The Lahore Biennale must be read within the broader history of biennales worldwide. The model originates with the Venice Biennale in 1895, which created the template of the recurring, city-wide international exhibition. Venice was followed by São Paulo, which gave Latin America its first international platform, and later by Istanbul, Sharjah, Dakar, Kochi-Muziris, and countless others. Each has taken the Venice model but localized it: connecting global networks with local contexts, using art to stage civic conversations while also inserting their cities into global cultural circuits.

Biennales’ significance is multifaceted as they create concentrated moments when artists, curators, critics and collectors circulate, providing a platform to rethink national and regional narratives. They often function as civic showcases that cities and states use to reposition themselves culturally. In short, biennales are now both art-world events and instruments of cultural projection.

Younger city and region-led biennales — e.g., Kochi-Muziris, Dakar, Lahore, Karachi — are newer events that tend to combine heritage sites, local communities, and international networks. They aim simultaneously to build local cultural infrastructure and to introduce their cities to global curators, collectors and cultural journalists. Lahore’s use of forts, gardens and neighborhoods follows the same playbook, foregrounding the city’s specificity while opening it to transregional dialogues.

Major biennales function as soft-power tools by projecting curated narratives about a country’s culture, heritage and contemporary dynamism to international audiences. A biennale can present a more textured, culturally sophisticated image of a country than headlines alone permit, inviting long-term relationships, co-productions, museum loans, residencies and tourism.

Several overlapping reasons — like cultural visibility and city-branding — explain the proliferation of biennales. Cities use biennales to signal cultural modernity, attract tourists, and make themselves visible on global cultural maps. Biennales can be packaged as civic achievements with measurable visitation and PR impact.

Venice remains the apex of prestige, a stage-set for cultural diplomacy and critical debate. São Paulo asserted Latin American modernism. Sharjah and Istanbul foreground regional politics and heritage, drawing cultural tourism while shaping international discourse. Lahore’s contribution is distinct. It introduces Pakistan as a site of cultural vitality, heritage, and experimentation, reconfiguring how the country is perceived globally.

Lahore’s pattern of pairing exhibitions with public programs, residencies and publications follows this logic, fostering institution-building and ecosystem development. The art world prizes sites of exchange where curators and critics can “discover” artists. Biennales allow cities and organizers to insert local artists into international circuits, enabling market and institutional recognition. Scholarship shows how biennales localize global networks and globalize local scenes.

What this means for Lahore and Pakistan is that LBF has stitched together the positive mechanisms and has built curatorial capacity, activated heritage and public space for contemporary practice, while creating international visibility for Pakistani artists. That visibility also functions as a form of cultural diplomacy. The Biennale’s international audiences and publications offer a counter-narrative to reductive international images of Pakistan. Yet consistent with broader patterns, the lasting value depends on institutional consolidation — through archives, maintenance of public commissions, educational pipelines — and on how widely the benefits are distributed beyond festival moments, within the city and beyond.

The Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF) has, within less than a decade, emerged as one of the most influential actors in Pakistan’s cultural landscape. It has not only staged large-scale contemporary art exhibitions but has reshaped how art is produced, exhibited, and experienced in the country. By transforming heritage and civic spaces into sites of artistic encounter, by building infrastructure where none previously existed, and by bridging institutional gaps between artists, public bodies, and audiences, the Foundation has altered the very ecology of Pakistan’s contemporary art scene.

The Lahore Biennale Foundation has transformed Pakistan’s contemporary art scene by reimagining the city as museum, heritage as living canvas, and art as a public right rather than an elite pastime. It has also positioned Lahore within a global genealogy of biennales, aligning Pakistan with a tradition of cultural events that serve as engines of soft power, civic imagination, and institutional growth.

In a world where biennales increasingly proliferate as cultural signatures of cities and nations, the Lahore Biennale’s achievement lies not in imitation but in specificity. It speaks from Lahore’s history, its public life, and its people. It shows that art in Pakistan is not only alive but civic, participatory, and globally resonant. If the work ahead is to consolidate and sustain these gains, the achievement so far is undeniable. Lahore, through its Biennale, has announced itself as a city of culture, conversation, and contemporary imagination.