Aarish Sardar is in a candid conversation with the dynamic Qudsia Rahim about her visionary leadership and the transformative journey of LBF

Ten years on, the Lahore Biennale Foundation (LBF) has become one of Pakistan’s leading cultural institutions, transforming how art is created and experienced in public spaces. However, the five weeks of exhibitions and performances are only the visible part of a complex system—an ecosystem of negotiations, permissions, civic involvement, and design thinking that makes it all possible.

When I first approached Qudsia Rahim, the founder and driving force behind LBF, my interest extended beyond the artworks that fill Lahore’s gardens, forts, museums, galleries, and streets. I wanted to understand the unseen frameworks supporting them. How does one establish an institution from scratch in a country with limited infrastructure for large-scale cultural production? How do you navigate bureaucracies, mobilise public agencies, and create systems that allow art to circulate freely without censorship or red tape?

In this conversation, Rahim reflects on ten years of learning, persistence, and pragmatism—an institution that quietly shapes the conditions enabling true public art to emerge.

Aarish Sardar: First comes first–congratulations on your recent appointment to the board of the International Biennale Association.

Qudsia Rahim: Thanks, Aarish. I am both honoured and excited to represent Pakistan at this prestigious platform.

Aarish: You began your career as a glass artist and later moved into curatorial roles. I wonder what inspired the shift in your path—from creating art to directing the Biennale and shaping cultural frameworks—from practising art to enabling it and driving change in the larger cultural landscape?

Qudsia: Glass, like any other fragile medium, taught me the discipline of process—you can’t rush it, and you can’t fake it. It’s about control and surrender in equal measure. That sensitivity to timing and transformation has stayed with me. At the Zahoor ul Akhlaq Gallery, I began to see how ideas could travel—how an exhibition wasn’t just about objects on the walls, but about creating dialogue, systems of exchange, and trust between artists and their audiences.

During a meeting at the Goethe-Institut around that time, its director introduced me to the biennale format for the first time. I remember feeling completely overwhelmed—it seemed on a massive scale, a project that could take over an entire city. But something about it resonated deeply within me. I realised that this was another kind of material challenge, simply on a larger scale.

What glass taught me—about precision, fragility, and transformation—now manifests in systems and structures. The Lahore Biennale Foundation, in hindsight, grew from that same impulse: to work with something unpredictable and shape it into coherence.

Aarish: Looking back, what have been the most defining milestones for LBF over this decade, in terms of system design?

Qudsia: When you say “a decade,” I don’t just think of the art itself; I think of the systems behind it and countless other things alongside. One of our earliest milestones, or defining moments, was persuading the Federal Board of Revenue that artworks are not commercial goods, but a distinct entity that requires its own system of operations. There was no precedent for temporarily importing artworks for exhibition—customs treated them as if we were bringing in phones or pens for sale.

I still remember going alone to meet the FBR Chairman to explain why we needed a legal exemption from the taxes that had been levied. During the first Biennale, we were required to deposit a bond of four million rupees to import just three projectors belonging to Shahzia Sikander. If we had been taxed as importers, the cost would have been impossible. Those negotiations were tedious but vital. Over time, we helped create a framework that now permits the temporary import of artworks for cultural exchange. That’s the invisible work—the scaffolding that most people never see. I am glad you asked me this question; I cannot tell you from the corners and crevices of the spaces full of challenges.

Aarish: It’s fascinating to see how much advocacy lies behind what appears to be a cultural event. Did government support come easily once you had these systems in place?

Qudsia: See, building the Lahore Biennale Foundation has been a journey of persistence, consistency, and hard work. Over the years, the government’s trust and support have grown through our continued commitment and delivery. We’ve always viewed collaboration with the state not as a compromise, but as a vital partnership—one that allows us to create meaningful, inclusive public engagements. We remain sincerely grateful to all those within the government who have believed in and supported our vision.

Aarish: The Biennale lasts exactly five weeks, giving people time to revisit, reflect, and absorb the experience. That concept of slowness as a form of care runs through all three editions of the Biennale. Each seems to build on the previous one while expanding outward. How did you picture that trajectory?

Qudsia: That focus on slowness is deliberate. I’ve always been concerned about the speed of spectacle—the transient aesthetics and euphoric, rapid “diva situations” that can flood our cities. Rethinking this hyper-culture is probably the reason behind our commitment to slowness. It’s about taking responsibility for what we present to the public. If you keep the displays open longer, you remove more for people to process later.

This philosophy was solidified by the best advice I ever received, “Think three Biennales ahead.” This encouraged us to build a long-term vision, setting small, steady goals one by one. The first edition of Shehr-o-Funn was an exploration of whether such an event could even take place in Lahore. I curated it with the support of a small team and the valuable guidance of many, including Raza Ali Dada, Aisha Jatoi, and especially Prof. Iftikhar Dadi. Our focus was on artists connected to Pakistan and the broader South Asian region. It was an intimate and necessary engagement—for a country with such a rich artistic legacy, a biennale is a fitting tribute. However, one thing was clear: we wanted the academic element to stay strong and expand.

Fortunately, we developed the academic forum under the leadership of Prof. Iftikhar Dadi. The first edition went viral, and the public quickly recognised the LBF’s timely debut. Over 180 articles were published about the first edition, both nationally and internationally, in major periodicals. Shwetal Patel of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale also mentioned it in his book. Many critics have described it as a game-changer in the region. Prof. Dadi introduced us to Hoor Al Qasimi, who was connected to Salah Hasan, the Dean of The Africa Institute in Sharjah, and had heard about LBF.

For the Biennale’s second edition, Between the Sun and the Moon, curated by Hoor, our aim and clear objective was to link Pakistan with the global art community. Hoor played a key role in this, bringing a diverse group of artists from the MENASA region to Lahore for the first time, and transforming everything. As a result, international critics started to notice, leading to coverage in major publications such as The New York Times and Frieze. Lahore became one of the 20 must-visit places.

The third edition, Of Mountains and Seas, with John Tain, fulfilled that long view. This brought attention to Pakistan from the Far East and Asia as a whole. Each Biennale has been a study in systems—artistic, civic, and ecological. It’s only been possible by having a grip on our narrative.

Aarish: You often emphasise “integrating systemic approaches” at the institutional level. What do you mean by that?

Qudsia: Institutions, by nature, can sometimes become static — places that preserve ideas rather than evolve them. Systems, on the other hand, are dynamic and living frameworks; they allow movement, exchange, and adaptation. I’ve always envisioned LBF not as a fixed or closed structure, but as an enabling mechanism — one that empowers others to act, to experiment, and to contribute.

My role is not to dictate curatorial directions, but to ensure that the systems we build continue to support dialogue, access, and collaboration. LBF’s purpose has never been about centralising power; it’s about creating conditions where it can be shared and multiplied. When people are able to enter a space, participate meaningfully, and leave their imprint, that’s when the system truly comes alive.

In the long run, I hope the Lahore Biennale Foundation continues to evolve as a responsive institution — one that remains diverse, adaptive, and attuned to the changing cultural and social landscape.

Take Mall Road, for example. Since the first Biennale, I’ve worked to reclaim that stretch as a cultural corridor. We collaborated with commissioners, civil and military authorities, to convert forgotten heritage spaces — old bunkers, buildings, and gardens — into galleries and exhibition spaces. I see it as urban acupuncture: small, precise interventions that gradually rewire the city.

I was once offered a National History Museum project at Greater Iqbal Park, and I proposed to the government bodies that we work with Shermeen Obaid-Chinoy, as the best person specialising in preserving national history through the Citizens Archive of Pakistan. I went to CM’s office, attending every meeting till the project was handed over to them, and they did an excellent job.

But it’s not just about physical spaces. It’s about networks, dialogues, and relationships — connecting artists, audiences, policymakers, and communities in ways that ripple outward. Every exhibition, workshop, or intervention is part of a larger ecosystem. By thinking systemically, we can create opportunities that are adaptive, responsive, and regenerative rather than fixed.

In that sense, LBF becomes less a singular authority and more a connective tissue — a platform that supports experimentation, nurtures emerging voices, and leaves room for unexpected collaborations to flourish.

For example, we never hold back any of our international artists while they are in Lahore, as they meet with new peers from academia, independent galleries, curators, art critics, or public body chairholders and develop new connections and projects, if they wish to.

Aarish: That’s both sensitive and strategic. You’ve also been vocal about environmental sustainability — long before it became a global art trend. How did that enter the Biennale’s framework?

Qudsia: It developed naturally, as we have a year-long calendar of events, and we learn from them. Around 2018, Lahore’s smog crisis was worsening, and I kept asking myself, “What is our role as cultural space makers and facilitators?”

This led to the founding of Afforestation Lahore, a coalition comprising civil society and government agencies. I approached Mujtaba Piracha, the then Commissioner of Lahore, and suggested a consortium of government and civil society to address urgent matters.

Various minds, including Kamil Khan Mumtaz and his son, Nayyar Ali Dada and Raza, Imrana Tiwana, Rafay Alam, and many other notable members, all with different perspectives, first banned single-use plastics and compiled a list of indigenous trees — something even the Parks and Horticulture Authority lacked — and began planting.

Based on this consortium, comprising academics, institutions, the government, and civil society, we successfully hosted the last Biennale and effectively explored the theme of sustainability.

After planting 2.5 million trees, we developed the Green School Certification Programme and later Zero Waste was initiated as a result of this effort. We realised that if ecological awareness isn’t institutionalised, it dies with individual enthusiasm. So we embedded it into education.

Art and design thinking can solve real problems — it’s all designed in its problem-solving context, just applied differently. I genuinely respect the finest bureaucrats, such as Omer Rasul (DG of the Civil Services Academy) and the Late Abdullah Sumbul, who both taught me how to work effectively within the bureaucracy.

Design can solve any problem, if not entirely, but episodically and I am a firm believer. Now the project has been taken up by the Govt of Punjab and running it successfully.

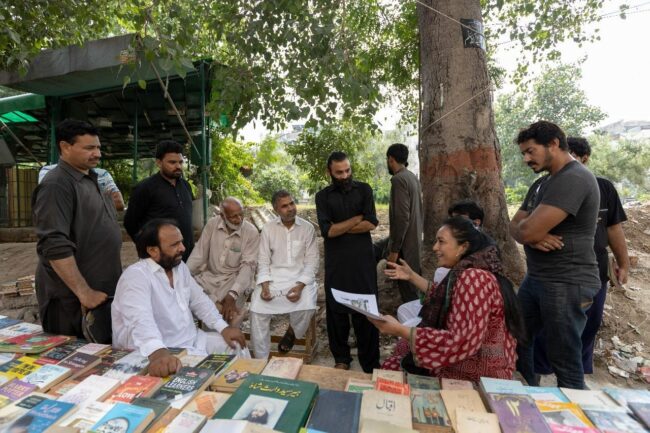

Meeting with stakeholders at the Sunday Book Market, Mall Road, Lahore, 2023

Aarish: There’s often a perception that the Biennale doesn’t issue open calls or publicly announce its curatorial themes — that participation can feel somewhat closed. How do you respond to that, and how does inclusion actually work within LBF’s framework?

Qudsia: We do have programs that have open calls — in fact, we have been working through open calls from the inception of the Foundation, for the last 12 years. As for the Biennale, if the curator decides to have an open call or not, we follow their lead.

Biennales are conceptualized by the curator/s of their editions as it’s about building relationships and systems of trust. We welcome individuals who approach us, but specific standards and responsibilities are in place.

We seek artists, curators, and institutions who work diligently — those who demonstrate seriousness in their practice and contribute meaningfully to the broader conversation.

When we began, there were about ten collateral events; now there are more than fifty. The Biennale directly works with institutions by involving them within our programming — this way we are able to work with a wider student body and build another layer of engagement with our audiences through collaborations with institutions such as NCA, BNU, Punjab University, LUMS, Kinnaird College, COMSATS, and Lahore College.

I’ve also encouraged stronger partnerships with government bodies, and they’ve been remarkably supportive. The Walled City of Lahore Authority, under the leadership of Kamran Lashari, and the Aga Khan Cultural Network have both been instrumental in opening up public spaces and heritage sites to us.

Ultimately, the idea is not to expand for the sake of scale, but to ensure that whoever becomes part of the Biennale and shares a sense of purpose and responsibility, gets the due recognition. That’s what allows the city to resonate with art — not as a spectacle, but as a collective act.

Aarish: That civic dimension is remarkable. Yet public art in Pakistan often faces moral or political resistance. Have you encountered backlash, controversy, or censorship?

Qudsia: Backlash is healthy — it keeps you on your toes. I don’t take my position for granted. Inclusion shouldn’t be performative — it should be structural.

We make sure that all forms of grievances from the underrepresented voices are included, yet embedding plurality into the programme without making it a headline. We don’t need to advertise tolerance; we need to practise it.

I’ve been fortunate to work with thoughtful curators and an informed team. At the heart of it, everything begins and ends with humanity — and I do believe we are, by nature, tolerant people. We don’t praise, celebrate, appreciate ourselves, as warm Muslims and great Pakistanis.

When it comes to conditions from government bodies, that’s not unique to Pakistan — it happens everywhere. LBF is fully aware of its social and political landscape. We navigate it carefully, and artists do the same. They know their limits and their audiences — and they choose their expressions accordingly.

Aarish: Following the narrative, what do you think about activism through art, and whether there’s any propaganda attached to it — especially in public spaces?

Qudsia: Let’s bring this to an end. There are many forms of activism — it’s visible on the streets in the public sphere, sometimes with placards, sometimes through writing or performance.

But our approach isn’t about pointing fingers or making loud statements. We’re interested in reclaiming our narrative — in understanding how alternative, knowledge-based systems can respond to social and political contexts.

For instance, we worked on a project called Intersections: Where the Bus Stops. It started as an open call for artists, architects, and designers to rethink something as ordinary as a bus stop — especially given how women and families often had no proper place to wait or no idea when the next bus would arrive.

We received a range of proposals, selected a few, and built new bus stops across the city. The project did really well, and eventually, the government took it forward and expanded it to other areas. That’s what impact looks like to me — not slogans, but systems that respond and evolve.

After the Biennale, we saw a ripple effect — from sustainability projects at YMCA to embassy-led exhibitions on environmental awareness. So yes, that’s the kind of activism we believe in: think collectively, act independently, and let good ideas travel.

Aarish: Your approach to funding seems guided by the same design thinking. Large-scale cultural events often face the challenge of balancing. How has LBF maintained that balance between financial sustainability and curatorial independence?

Qudsia: The early years were certainly challenging, but over time, I learned the importance of setting clear boundaries. In ten years, no one has ever asked for favours or insisted on inclusion. Our partners fund and support us, but they never interfere — and that autonomy is invaluable. Even the government has been remarkably respectful.

The integrity of our programming is non-negotiable. Every artist, project, and collaboration is selected through a rigorous process of research and dialogue, in alignment with the Biennale’s conceptual framework — never through external influence.

We have established a system of mutual respect in which our partners understand their role is to enable, not direct. This understanding has been crucial in maintaining the Biennale’s critical relevance and structural independence.

Raza mainly oversees exhibition design and branding, ensuring visual and conceptual consistency across all our initiatives. We display the government logo with pride, not as an endorsement, but as a symbol of partnership and civic confidence. It’s a matter of context and clarity. The strength of our foundation board reinforces this integrity.

Aarish: How do you strike a balance in the selection process — between digital works, paintings, sculptures, installations, and more tactile mediums?

Qudsia: I work very closely with the curators, but they have complete autonomy in making their selections. My focus is on creating a system that supports their decisions — a framework that allows different forms of practice to coexist and thrive.

We don’t set quotas or categories; if the outcome is entirely digital or entirely physical, that’s fine. What matters is that the work communicates effectively and aligns with the Biennale’s theme and the overall objectivity.

Aarish: How do you measure the Biennale’s impact beyond attendance numbers?

Qudsia: We do gather data — ticker counts, visitor surveys, institutional feedback — but numbers only reveal part of the story. The true measure is in the ecosystem.

Ten years ago, there were only a few galleries; now, formal and informal art spaces have increased. Pakistani artists are being collected internationally, invited to residencies, and paid fairly. The ecosystem has grown — visionaries have evolved.

Cornell (Reader) and Harvard, British Council, Embassies within Pakistan, are amongst the oldest, Guggenheim (Abu Dhabi) is one of the younger sponsors. When people travel abroad, they tell us that others now recognise the Lahore Biennale and speak highly of its impact. That visibility positions Pakistan positively on the global stage.

It’s honestly impossible for me to name or thank everyone who has been part of this journey — hundreds of LBF friends have stood by us, trusted our vision, and worked tirelessly to strengthen the foundation.

Their support has never been passive; they have engaged, contributed, and helped refine the systems that keep the Biennale alive. Through their efforts, and the ongoing dedication of numerous collaborators, Pakistan’s artistic presence has grown deeper and broader.

Equally important are the visitors who attend the Biennale, who explore the city and contribute to the local economy through tourism and cultural exchange.

Of course, such support does not come without effort — we have invested our time, energy, and resources. Yet, when the work is moving in the right direction, it attracts this extraordinary network of friends and collaborators, all of whom believe in our goals and share our commitment to nurturing Pakistan’s cultural ecosystem.

LBF can’t do everything on its own, of course, but if someone has creative ideas, I’d say — go ahead and make them happen. (laughs)

Aarish: And what about you — after ten years of designing systems, do you feel optimistic about where all this is headed? Any wishful thinking ahead?

Qudsia: I wouldn’t call myself an optimist — I’m pragmatic. (laughs) Optimism can be unquestioning; pragmatism gets things done. I believe in designing for continuity.

The Biennale isn’t about me; it’s about enabling others — artists, students, institutions, and creative concerns — to take ownership of public space. Plurality isn’t about having one Qudsia everywhere; it’s about many people doing different things well.

That’s the future I want — where art is not ornamental but infrastructural, woven into how the city breathes.

We always follow the rules carefully. I still remember when we applied for Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy (PCP) board certification in 2016, which is granted to organisations in Pakistan that meet standards for governance, financial management, and programme delivery.

They won’t grant approval if there’s any lack of transparency in your documents. When we met one of the PCP instructors, who said, “Madam, I have never seen the documents of any registered society arranged and curated so beautifully.”

He mentioned that the only other example that came close was NAPA in Karachi. We passed with flying colours immediately, thanks to the meticulous approach of my dedicated team.

We are audited by KPMG, and our grants and financial records are publicly available on our website.

We have never worked randomly. I learned from observing my father, father-in-law, and husband, all of whom work with dedication and zeal. I have no personal agenda — my approach is research-based, well-designed, and intentional.

Each time I review, I aspire to pass it on and focus on other parts of my life. However, it’s not simple — I am deeply emotionally attached to this. It’s a system I have built and nurtured, and I cannot relinquish it without a stable, sustainable replacement in place.

Currently, the foundation’s board members and I still raise funds ourselves, which isn’t a sustainable long-term approach. Internationally, biennales benefit from endowment funds and dedicated boards that ensure their continuity beyond individual efforts, and I hope that, with the systems we’re developing, we will achieve the same goal.

That will be true success — when the Lahore Biennale becomes an autonomous institution with many hands guiding its future.

Aarish: Thank you very much, Qudsia, for taking the time to discuss so many aspects of the Biennale that haven’t been explored before. Is there anything you’d like to add before we conclude?

Qudsia: Thank you, Aarish. I genuinely enjoy these conversations because they allow us to reflect — not just on what the Biennale presents outwardly, but also on the processes, challenges, and ideas that shape it behind the scenes.

I want to add just a few things: to all those who feel they haven’t yet had a chance — wait. The Lahore Biennale is here to stay and to grow. If you aren’t part of this edition, you may be part of the next one, or the next after that. There will always be room for new voices and ideas.

I believe that nurturing such a framework is only possible if our academic and cultural institutions invest in research-driven, knowledge-based, and system-focused projects.

This should become integrated into our curricula and pedagogical approaches — shifting from isolated initiatives to ongoing, systemic practices. Only then can we foster the intellectual and creative ecosystems from which future Biennale editions can genuinely benefit.