Curated by Arshad Faruqui, Tasees showcased works by Graduates of VM Centre of Traditional Arts: Alefiya Abbas Ali, Amna Fraz, Dilshad Asif, Fatimah Agha, Kaneez Fatima, Khalifa Shujauddin, Mehrin Haseeb, Maryam Cheema, Saman Ansari and Sana Habib.

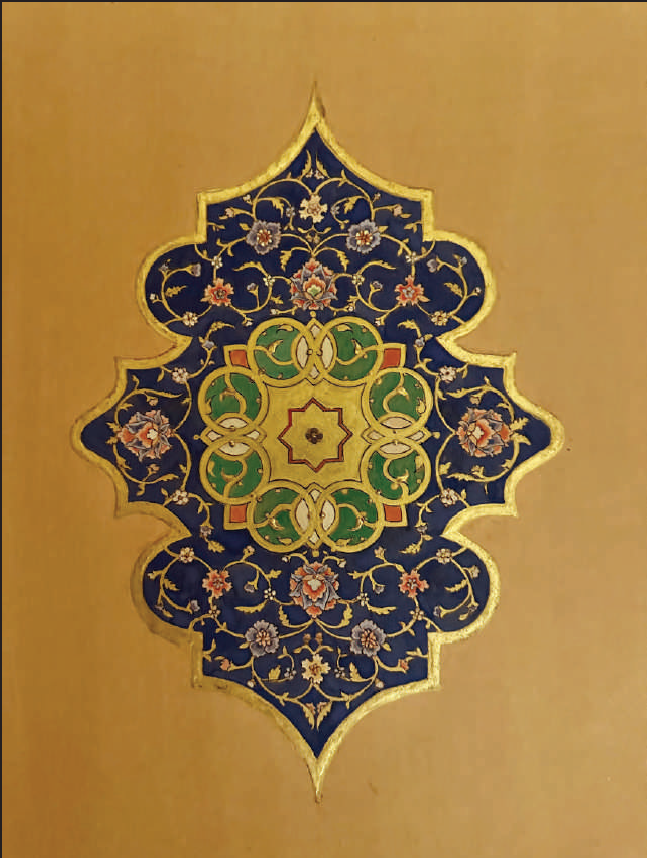

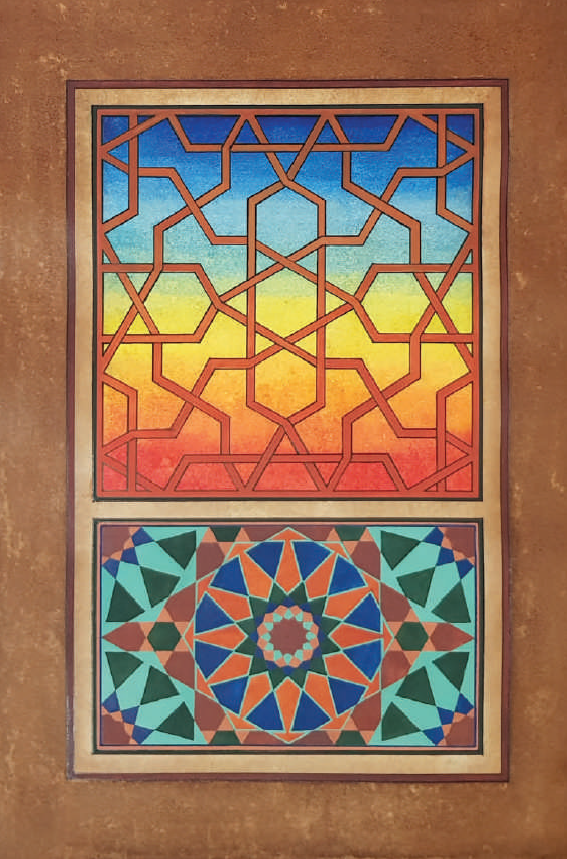

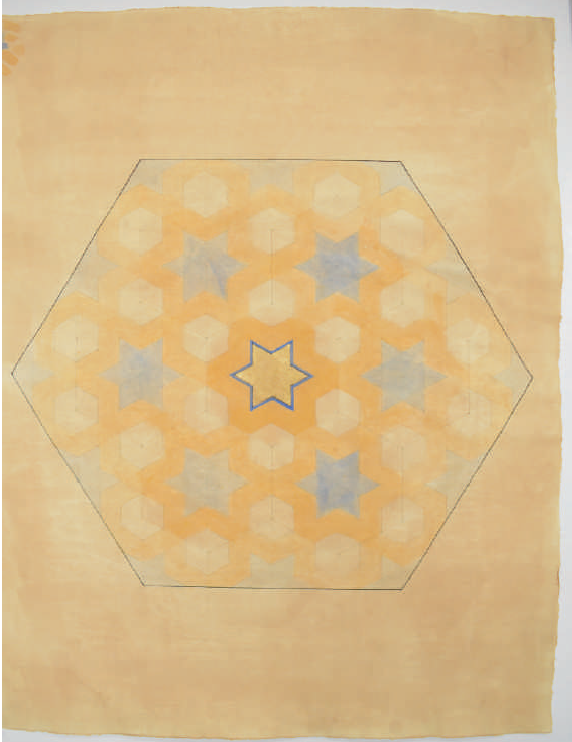

Tasees (base;foundation in Urdu) was an exhibition centered on Islamic patterns. Sacred Geometry itself is a profound and ancient concept that explores the mathematical and geometric principles believed to underlie the creation and structure of the universe. It is an interdisciplinary field that combines mathematics, art, philosophy, and spirituality to unveil the hidden order and harmony in the cosmos. The idea that certain geometric shapes and ratios possess inherent sacred qualities has been present in various cultures throughout history, reflecting a belief that the divine is encoded in the very fabric of reality.

At the heart of Sacred Geometry lies the notion that certain geometric shapes and proportions are universal constants, transcending cultural and temporal boundaries. These fundamental forms are thought to represent archetypal patterns that connect the physical and metaphysical realms. The study of Sacred Geometry involves exploring these patterns and their symbolic significance, often revealing a deeper understanding of the natural world. As such, then, a few primary exponents of Sacred Geometry can be named here, reminding us that this field of spiritual endeavor is not restricted to any one culture or era.

Pythagoras (circa 570 – 495 BCE), the ancient Greek mathematician and philosopher, is often considered one of the earliest proponents of Sacred Geometry. The Pythagorean theorem, which relates the lengths of the sides of a right triangle, is a foundational concept in Sacred Geometry. The Pythagoreans believed in the mystical significance of numbers and geometric shapes, considering them to hold the key to understanding the cosmos. Plato (428/427 – 348/347 BCE), another influential figure in the development of Sacred Geometry, emphasized the role of geometry in understanding the nature of reality. In his dialogue “Timaeus,” Plato proposed the idea of a “divine craftsman” who used geometric forms to create the physical world. The Platonic solids—tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron, and icosahedral—are central to Sacred Geometry and are believed to represent the building blocks of the universe.

During the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci (1452 – 1519 CE), a polymath of extraordinary talent, explored the intersection of art and science. His Vitruvian Man, a drawing of a man inscribed in both a circle and a square, embodies the principles of Sacred Geometry. This iconic image symbolizes the harmonious relationship between the human body and geometric proportions, suggesting a connection between the microcosm and macrocosm. Soon after, Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630 CE), the German astronomer and mathematician, made significant contributions to the understanding of planetary motion. His work on the relationships between the orbits of planets led him to propose the “Platonic solids” as a model for the arrangement of planetary orbits. While his specific model was later discarded, Kepler’s exploration of geometric patterns in the cosmos reflects the enduring influence of Sacred Geometry.

Within modern architecture, Buckminster Fuller (1895 – 1983 CE), an American architect, inventor, and futurist, introduced the concept of the “Vector Equilibrium,” a geometric form that he believed represented the ultimate balance and harmony in the universe. Fuller’s exploration of geometric structures and their applications in design and architecture contributed to the contemporary resurgence of interest in Sacred Geometry.:

Sacred Geometry continues to captivate the minds of thinkers, artists, and seekers of spiritual understanding. The idea that certain geometric forms and proportions hold inherent sacredness persists as a cross-cultural and transhistorical concept. Whether through the ancient wisdom of Pythagoras and Plato or the visionary insights of da Vinci and Fuller, Sacred Geometry remains a fascinating lens through which we can contemplate the interconnectedness of mathematics, art, and the divine in the grand tapestry of existence.

Islamic art and architecture are rich with examples of Sacred Geometry, and several key figures in Islamic history have contributed to the development and application of geometric principles in Islamic art. While it’s important to note, as above, that the concept of Sacred Geometry is not exclusive to any particular culture or religion, certain Islamic scholars and artists have played a significant role in exploring and expressing geometric patterns within the context of Islamic art and architecture.

Al-Farabi (c. 872 – 950 CE), a renowned Islamic philosopher, mathematician, and scientist, made contributions to the understanding of music, logic, and ethics. In the realm of geometry, his work involved discussions on the mathematical relationships found in music, which often included geometric considerations. While not exclusively a Sacred Geometry exponent, his contributions to various disciplines influenced the broader intellectual and artistic context. Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) (965 – 1040 CE), also an Arab scientist and polymath, is best known for his groundbreaking work in optics. While his contributions to Sacred Geometry are not as direct, his investigations into light and optics influenced later Islamic artists in their use of geometric patterns, particularly in the design of intricate geometrically patterned windows known as “muqarnas” that adorn many Islamic buildings.

Omar Khayyam (1048 – 1131 CE), Omar Khayyam, a Persian mathematician, astronomer, and poet, is best known for his work on algebra and his contributions to the understanding of conic sections. Again, while not a strict proponent of Sacred Geometry, his mathematical insights influenced later Islamic scholars and contributed to the development of geometric patterns in Islamic art.

Al-Jazari (1136 – 1206 CE), an engineer and polymath from the Islamic Golden Age, wrote the influential book “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.” While his primary contributions were in the field of engineering, his intricate designs and understanding of geometric principles had an impact on the artistic and architectural expression of Sacred Geometry in Islamic cultures.

Many anonymous artists and craftsmen throughout Islamic history have played a crucial role in expressing Sacred Geometry through intricate patterns in mosques, palaces, and other structures. In the present day, contemporary artists and designers continue to explore and create Islamic geometric patterns, adapting traditional principles to modern contexts. Islamic Sacred Geometry is often manifested in various art forms, including the distinctive geometric patterns found in Islamic architecture, such as the elaborate tilework, calligraphy, and muqarnas.

Pakistan has the extreme privilege to have Makli, located in the Thatta district of Sindh. According to the curatorial note “It is the largest necropolis and steeped in rich history. Spanning over 500 years, the site features an array of tombs and monuments of varying sizes and styles, each adorned with intricate decorative details. A group of artists have collaborated to create art that showcases the site’s vivid colours, intricate motifs, and unique patterns.The collection, reflects the diverse range of motifs, structures, and materials found at the site and

the various means of interpreting them. Geometry, as a source of inspiration, has enabled these traditional artists to explore new facets of their artistic abilities while staying true to their roots. This is a testament to the site’s cultural significance, the artists’ reverence, and the collaboration between art and history.”

All of the ten participants of Tasees were accomplished practitioners of this art, no doubt a testimonial to the dedication of the VM Centre of Traditional Art. That the artists hailed from a diversity of backgrounds was also to be noted. At this point, in order to turn our attention to the individual statements given by the artists, we may say along with Ricoeur that “every narrative includes discourse inasmuch as any narrative is no less something uttered than, let us say, lyric song, confession, or autobiography.” We can, with some ease and confidence, include visual art in the list. Further on in the vein, Ricoeur states: “Utterance, for its part, does indeed come out of the self referential character of discourse and refers to the person who is narrating. Narratology, however, strives to record only the marks of narration found in the text.”In simpler terms, utterance is basically when someone says something. It comes from the idea that when we speak or express ourselves, it’s influenced by our own experiences and perspectives. So, when you say something, it’s like a piece of you coming out in your words. Narratology on the other hand, is the study of how stories are told. It focuses on analyzing the structure and elements of narratives. The paragraph mentions that narratology is mainly interested in looking at the signs or features of storytelling within the text itself.

How does this relate to artists creating their own spirituality:? Artists, like anyone expressing themselves, bring forth their thoughts, feelings, and experiences into their art. This act of expression, or “utterance,” is a way for them to convey something personal and meaningful. When they create, it’s like a part of their own story is being told through their art. In parallel, just like narratology studies the structure of stories, artists may also consider the technical aspects of their art — the brushstrokes, composition, colors, etc. This is similar to the narratological focus on the marks of narration in the text. So, in a way, artists can be seen as narrators of their own spiritual or personal stories through their creative expressions.

The works of Alefiya Abbas Ali, Amna Fraz, Dilshad Asif, Kaneez Fatima, Khalifa Shujauddin, Mehrin Haseeb and Saman Ansari clearly demonstrated high levels of skill, creativity and understanding of various media, bringing a truly sophisticated tone to the exhibition. One must remember that the buildings and burial sites of Makli no longer retain any visible trace of pigments – no doubt closer scientific investigation and research may help us recreate the actual colours. Also, in all likelihood the area was not allowed to remain barren of trees and shrubbery either, since it is apparent that Makli was an important necropolis, and it would have had a certain number of living inhabitants at any given point. In many ways, these artists reconstruct our imagination of what Makli may have looked like in the past, by bringing to our attention, intricate and detailed renditions of patterns and floral motifs as well.

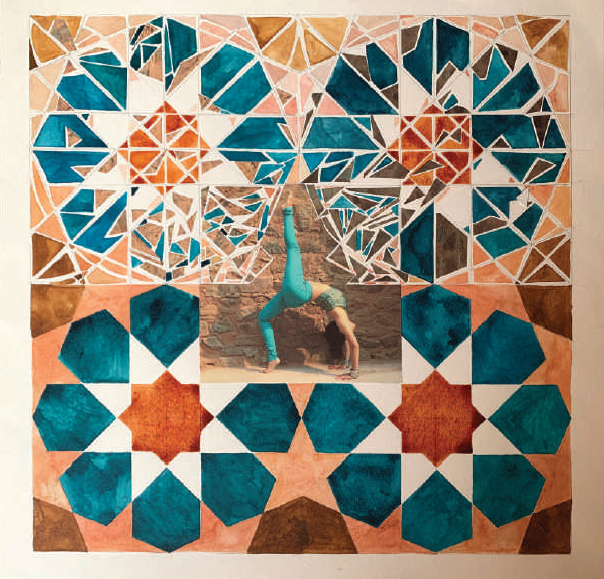

Maryam Cheema and Fatimah Agha chose to extend their efforts into the sculptural world. Geometry, as was noted earlier, was hugely intrinsic to the architectural aspects of Makli, and these artists had incorporated all the narrativity of the necropolis. In the case of Cheema, floral motifs were taken directly from stonework at the site and transposed into three-dimensional forms to create a hanging chandelier of sorts. Agha’s ‘staircase’ sculpture attempted to utilize the concept of a rising spiral or vortex of the spirit ascending to the skies. Lastly, Sana Habib explored the possibilities of collage-work by combining photographs of yoga positions within areas of geometrical patterns, directly alluding to the connections between the human body and the universe.

Sacred Geometry continues to captivate thinkers, artists, and seekers of spiritual understanding. It transcends cultural and temporal boundaries, providing a lens through which to contemplate the interconnectedness of mathematics, art, and the divine in the grand tapestry of existence. The exhibition at Makli exemplifies how traditional artists draw inspiration from geometry, creating art that resonates with cultural significance and historical reverence. In the words of the curator, Arshad Faruqi, “This is a testament to the site’s cultural significance, the artists’ reverence, and the collaboration between art and history.’

COMMENTS