Ameer Umer’s art merges historical influences with modern critique, redefining identity through innovative, introspective portraiture.

Exactly one hundred years ago, the Raj, an era of British colonial rule in India (1858-1947), saw profound changes in Subcontinental society, economy, and culture. At the time, the Indian National Congress, under M. K. Gandhi’s leadership, was at the forefront of anti-colonial resistance. Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns aimed to dismantle colonial authority and address issues of social inequality, which paralleled other global movements for decolonization and social reform. In Europe, the aftermath of World War I saw the rise of Modernism and Surrealism. Modernism was a broad cultural movement that rejected traditional forms of art, literature, and social organization, advocating for new ways of understanding reality.

Modernist artists like Picasso, and Duchamp, and writers like Virginia Woolf and James Joyce questioned established norms and sought innovative forms of expression. Their work responded to the disillusionment with pre-war values, a mood exacerbated by the devastation of the war. Surrealism, which emerged in the 1920s, took these critiques further by delving into the subconscious and irrational. Artists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte created dream-like, fantastical imagery that defied logic. This movement wasn’t just about art; it was also a form of social rebellion against conservative values. At first sight and in the context of Ameer Umer’s work, this resonates with how his portraiture might challenge conventional representations, drawing on postmodern critiques of realism in photography, as discussed by theorists like Marcuse and Sontag. This line of exploration is primarily evident in Umers small marker-on-paper portraits such as I See You In Dreams, In The Dark and Dusty.

In Russia, the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922 following the October Revolution marked the beginning of a new era shaped by Marxist ideology. The Bakhtin Circle, which critiqued and expanded on French Formalism, played a pivotal role in Soviet cultural theory. Mikhail Bakhtin, a key figure in this group, emphasized the dialogic nature of language and culture — ideas that can also be applied to visual arts.

This Soviet intellectual tradition, itself deeply rooted in ideological theory, is essential to understanding Umer’s unique departure from the norm. His engagement with Russian and Slavic influences may or may not highlight his refusal to adhere to dominant Western market forces, which tend to privilege Western art movements, but by referencing Russian academics, Umer is aligning himself with a less-explored lineage of thought in contemporary global art, positioning himself as part of a larger, more diverse cultural conversation. This critical move aligns his work with certain aesthetics that are still often marginalized in the global art market, and wholly neglected after the 1960s in Pakistan.

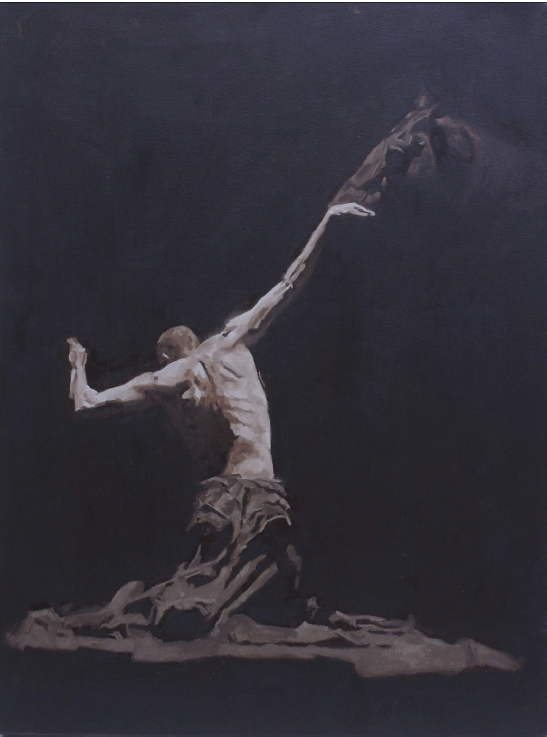

A passion for making the study of human anatomy completely grounds Umers practice, as it well should in any artist’s practice, and has lent itself to a conscientious decision to not exhibit until this task has been accomplished. This ethos stands out strongly in the works titled ‘Study’, ‘The Lost and Found, ‘Deep In The Dark 1’, and of course, ‘Anatomy’. In these works, the heroic form of anatomical studies becomes directly apparent.

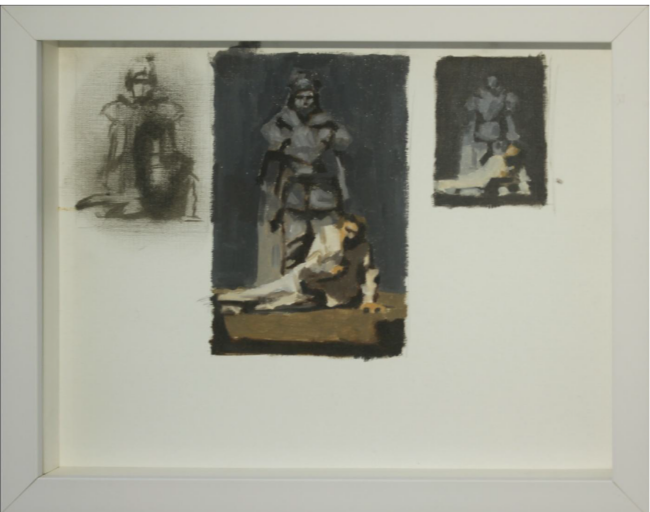

It seems the artist has been learning to draw and paint for a considerable number of years and already has a portfolio consisting of hundreds of works. The fact that he is a self-taught artist may explain the lack of direct live studies in his oeuvre since methodically acquiring that skill is one of the advantages of institutionalized art training. Yet, the exhibition was an engagingly instructive glimpse into the inner workings of Umer’s practice so far. As Umaina Khan, the curator, pointed out, the artist habitually creates preparatory sketches, tests colour palettes and makes light-and-shade studies quite often on the same canvas or sheet of paper and then derives a final image amidst the explorative fieldwork, as it were. The works titled ‘Him and Her’,’ Her Belonging’ and ‘Pale’ and finally, ‘Memories of the Night’ epitomize this highly idiosyncratic methodology. The artist does not restrict himself to brushwork alone, oftentimes preferring to achieve carefully crafted shapes by directly using his fingers.

Ameer Umer is also committed to understanding design principles and so we must return to Russian art in the early decades of the Twentieth century, to remind ourselves that the Bolshevik revolution created a direct impetus in art, toward communicative principles. Artists like Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Vladimir Tatlin made significant contributions to communicative art and design, particularly within the Constructivist and Suprematist movements, emphasizing abstract forms and shapes, reducing art to its most fundamental elements to convey universal, non-representational ideas. El Lissitzky, a key figure in Constructivism, pioneered innovative graphic design and propaganda art, using geometric shapes and bold colors to communicate revolutionary ideals. His famous Beat the Whites with the Red Wedgeposter exemplifies how art could serve as a direct visual language for political messaging. Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower) was a radical architectural project that embodied the spirit of collective, utopian design, blending form and function to inspire and communicate new societal ideals. True, these elements were only vaguely stated in the exhibition, and yet the landscape titled ‘Scape 1’ was a perfect example of the assimilation and transposition of graphic ideation.

In conclusion, we must recall that Russian modern art had two distinct phases – the experimental upsurge of the immediate Bolshevik years, and a later, more refined, seemingly more aesthetic era. It must not be forgotten that Lenin, as a Marxist theorist, was far from any position that would have sought to destroy literature, art and music – on the contrary, he was appreciative of these activities that, to his mind, are part and parcel of civilized societies. Notwithstanding Stalin’s authoritarianism, Russian art did develop its idioms, and one of Umer’s works is both a brilliant exemplar of that era as well as being a concretisation of the exhibition’s theme of conversing with the past. Mounted in a vintage gilded frame, the painting titled ‘Boy From The Village’ was a masterly combination of impressionist design and modernist texture. It was a rendition of a figure in a landscape virtually exploding with the white-gold light of a Russian summer. The features of the hatted boy were shadowed and intentionally indistinct while all around him, all else was figurally set ablaze by the communist ideology of the revolutionary rural folk.