As the art world’s attention increasingly turns toward the Arabian Gulf, with the launch of Art Basel in Qatar and a surge of institutional momentum in Saudi Arabia, Christie’s London stages a timely and profoundly resonant exhibition. Marwan: A Soul in Exile is not a commercial venture. No single work is for sale. Instead, it is a soulful reckoning with one of the Arab world’s most psychologically complex and emotionally charged painters.

Organised by Ridha Moumni, Chairman of Christie’s Middle East and Africa, the exhibition brings together more than 150 works by Syrian-German artist Marwan Kassab-Bachi, known as Marwan. The works on view, including paintings, drawings, and works on paper, are drawn from a network of institutional and private collections, including the Barjeel Art Foundation, the Dalloul Art Foundation in Beirut, the Berlinische Galerie, and the Pinault Collection, spanning Marwan’s six-decade career.

Born in Damascus in 1934, Marwan relocated to Germany in the late 1950s. He initially planned to continue on to Paris to study Impressionism, but Berlin’s post-war art scene, fractured and raw, captured the young artist. While his early interest lay in abstraction, Marwan gradually turned toward figuration, using his own body and face as subject matter. At the time, figuration was considered outdated in German painting, as younger artists such as Eugen Schönebeck and Georg Baselitz began pushing against convention.

While alienated from his homeland in Europe, Marwan remained tethered to the politics and poetics of the Arab world. As a young man in Damascus, he had surrounded himself with artists, intellectuals, and political activists. In Berlin, that fervor quieted but never disappeared. He continued to respond to events like the Six Day War, often painting his subjects as veiled expressions of alienation, displacement, and collective trauma.

While Marwan’s work engages with the intensity of German Expressionism and the radical spirit of Neue Wilde, his artistic voice is firmly rooted in the rich traditions of Arab culture. His portraits act as vessels of memory, spirituality, and political history. Over decades, the faces he painted became sites of mourning, resistance, and mystical reflection, with the spiritual language of Sufism meets the urgency of postwar artistic experimentation.

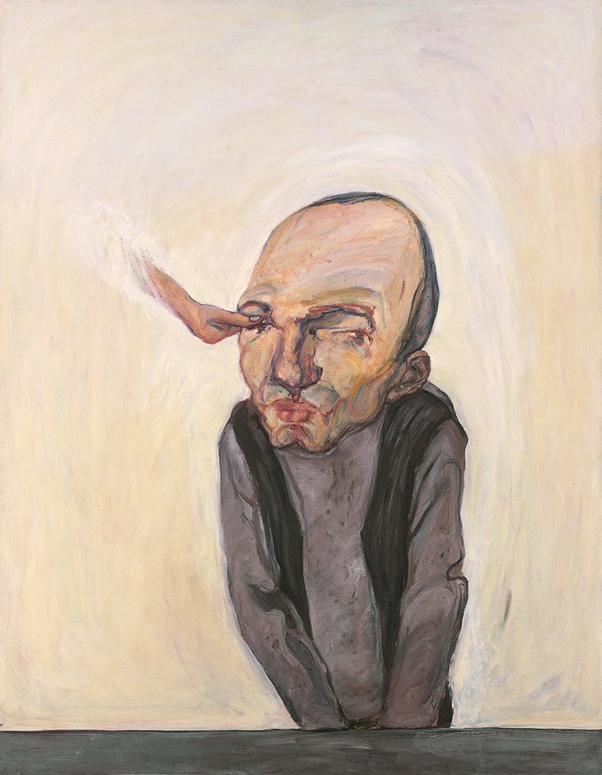

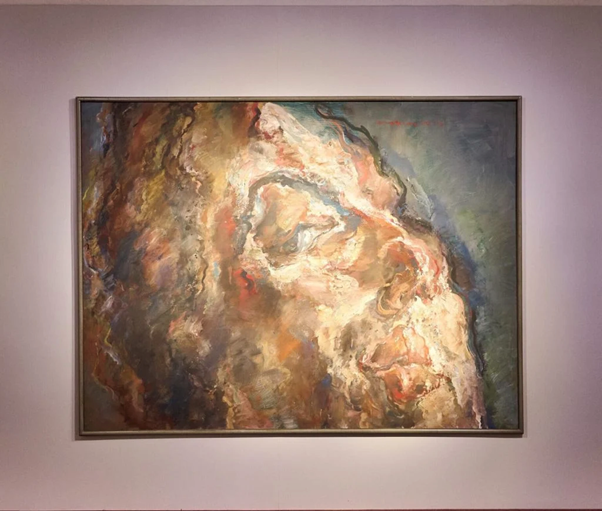

The human face was Marwan’s chosen subject, but never in search of realism. In his hands, the face became terrain. Each painting is layered with oil and memory, stripped of vanity and hollowed out by exile. The paintings act as confessions, as opposed to portraits. Beginning in the 1970s, Marwan’s iconic Head series emerges with a topographical intensity. A cheek becomes a hillside. A brow caves under emotional weight. Brushwork acts as an emotional excavation. The canvas turns into a site of psychological archaeology.

This period marks the beginning of what Marwan’s most iconic body of work, termed his Facial Landscapes. Within Marwan’s meditations, the face transforms into a map, as opposed to a mirror. These are not just expressions of psychic fragmentation, but meditations on identity as something built and broken across place and time. While their forms echo the mountainous topography of his native Damascus, particularly Mount Qasioun, their inner world lies in the revelation of the self as unstable, estranged, and transformed.

Earlier works, such as Seated Man (1966) possess an equal emotional intensity. The figure presses a finger into his own eye, in an act of interior scrutiny. These subjects do not plead to be seen. They attempt, sometimes desperately, to see themselves. What emerges in this exhibition is the full spectrum of Marwan’s visual language. Marwan does not offer clarity or closure, but rather offers the presence of endurance. These works do not resolve, but rather hold space for contradiction and ambiguity, reflecting the complexities of memory, identity and exile.