Curated by Venetia Porter with Imran Qureshi, Zohreen Murtaza, and Mahina Reki, the exhibition united leading voices in contemporary Pakistani art.

Like Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Kitab Ghar is built not of bricks but of memories, each artwork a city of its own, connected by invisible threads of longing and form.

Walking into Kitab Ghar at the National College of Arts felt like stepping into a living manuscript, one that breathed, shimmered, and shifted with every gaze. Curated by Venetia Porter with Imran Qureshi, Zohreen Murtaza, and Mahina Reki, the exhibition gathered some of Pakistan’s most compelling voices in contemporary art: Aisha Khalid, Rashid Rana, Imran Qureshi, Kaiser Irfan, Waqas Khan, Ali Kazim, Aakif Suri, Hamra Abbas, Attiya Javed, and Mahina Reki among others. Together, they transformed the book from an object of reading into a vessel of remembering.

The title itself carries cultural depth. Kitab, from the Arabic root k-t-b, is a word that threads through meanings to write (kataba), a writer (katib), a place of writing (maktaba). Ghar adds intimacy: a house, a place of return. Together, Kitab Ghar becomes both a house of books and a home of knowledge, a space where artistic practice meets the memory of the page and where the act of inscription becomes a metaphor for belonging.

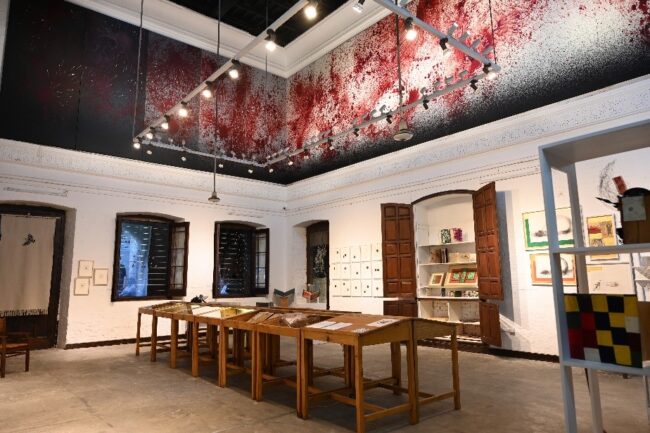

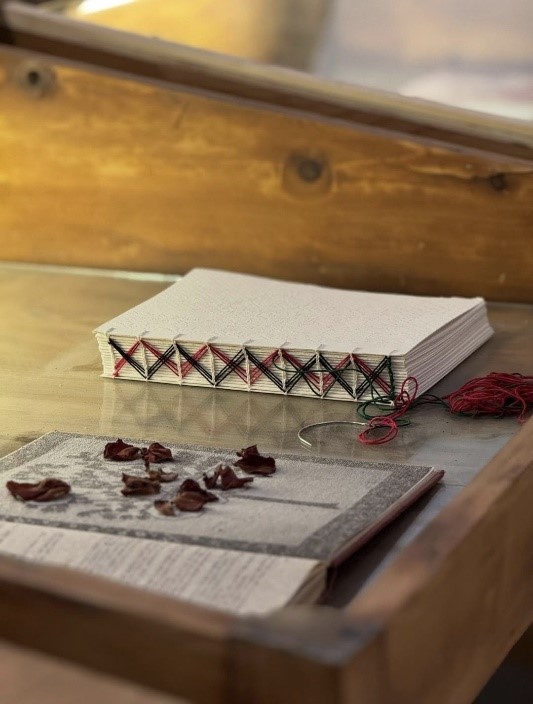

Marking 150 years of the National College of Arts, Kitab Ghar draws upon the institution’s enduring relationship with the arts of the book: miniature painting, wasli paper, and the craft of Imran Qureshi, both artist and co-curator, embodies this dialogue between tradition and transformation. This theme is perhaps most powerfully articulated in his large-scale installation, a panoramic freeze stretched high across the walls, which looms over the viewer like a fragmented cosmos. Qureshi repeatedly employs splashes of crimson acrylic, transforming the delicate floral patterns of Mughal miniature tradition into a visceral abstract expressionist spill. On this monumental scale, the cascading hues may be read as a profound echo of blood or the violence of history, prompting a critical reflection on beauty’s complicity in trauma. What appears serene is thus charged with inescapable tension, bearing the scars of history across its monumental surface.

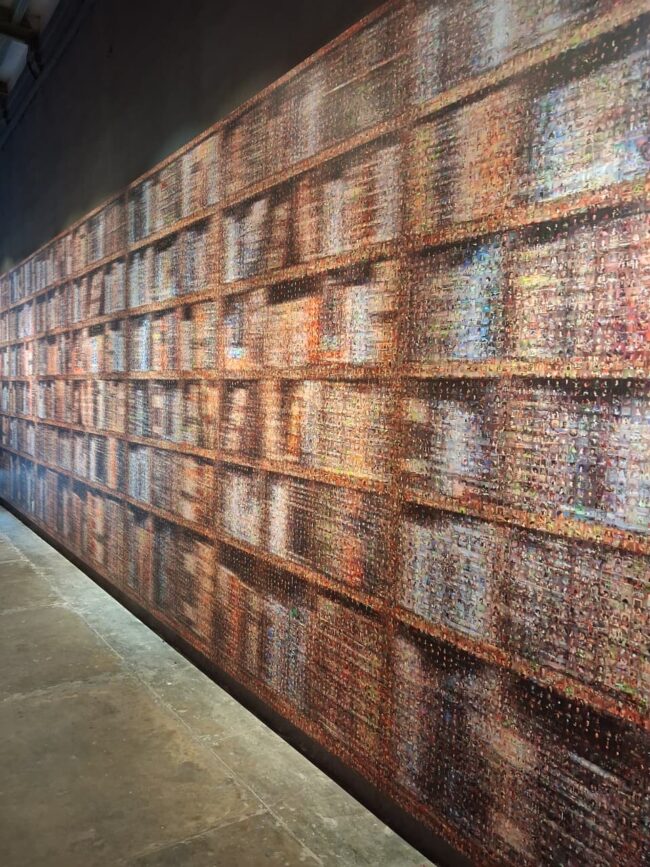

Rashid Rana, by contrast, dismantles this very idea of the handcrafted page. His Everything and Nothing IV, a digital mosaic of blurred books built from thousands of Renaissance paintings, turns the library into an illusion. The work questions how we consume knowledge in the digital age, where images masquerade as truths and archives dissolve into pixels. For Rana, the book becomes a paradox of excess: an infinite accumulation that yields nothingness. His digital mosaic is not a rejection of tradition but its contemporary echo, a manuscript rewritten by technology. Rana’s blurred mosaics reminded me of Borges’ Library of Babel; an infinity of unreadable books, each containing everything and nothing at once.

In one corner, Kaiser Irfan’s Takhti and The Language of the Birds (Asemic Journal) bring together the metaphors of learning, forgetting, and the mysticism of unreadable text. His panels, reminiscent of wooden slates once used in classrooms, carry marks that hover between script and gesture. His asemic writing, suspended between the legible and the lost, evokes the palimpsest of memory, how language erodes even as it endures. The journal, a six-month record of spontaneous mark-making, suggests that meaning is not contained in words but in the rhythm of their making and unmaking. Borrowing its title from the mythic Language of the Birds, Irfan gestures toward esoteric knowledge, the kind understood not through reading but through being.

Aakif Suri’s Dot by Dot, installed on the old library window grilles, transforms language into light. Inspired by Faiz Ludhianvi’s poem Naya Saal (New Year), Suri critiques the ritual of celebration without renewal, “If you are new, show me a new morning, a new evening.” The piece, composed of steel rods and spherical metal dots evoking Urdu diacritics, turns punctuation into poetry. Each “nuqta” becomes an act of writing and erasure, a meditation on how small marks shape meaning. Suri’s work, both austere and lyrical, frames the exhibition’s tone: the book not as vessel of fixed knowledge but as a living surface of reflection.

Ali Kazim’s Ruins Series felt like a landscape holding its breath, fragile and remembering. It brought to mind his tapestry of the bird in flight, a quiet guardian hovering above everything, watching over what time erodes. In Kitab Ghar, by revisiting Mantaq ul Tair Jadeed (A New Conference of the Birds), his artist’s book extends this same sensibility: pages that feel like small, protected terrains. Across ruins, bird, and book, Kazim traces a simple arc, the earth remembering, the sky watching, and the book preserving what might otherwise disappear.

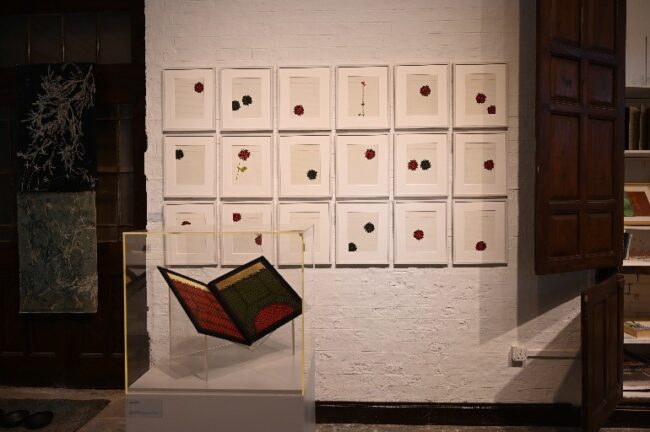

Aisha Khalid’s I Am and I Am Not was quiet yet overwhelming. Originally conceived as a written memoir, it transformed instead into painted manuscripts of selfhood. Gold leaf and crimson, pattern and repetition. Khalid’s language was one of control and surrender. I thought of her miniature brushstrokes as heartbeat and hesitation; each one an act of self-discipline that revealed vulnerability. Pamuk once wrote that the miniature painter painted not what he saw, but what he remembered. Khalid and Qureshi inherit that memory turning ornament into confession.

Into this conversation enter the textile and feminist practices that extend the miniature’s attention to craft into the realm of memory and domesticity. Similarly, Mahina Reki’s Tree of Life connects geographies of pain, from Baluchistan to Gaza, through silk thread and cloth. Her work is both tactile and political, turning ornament into resistance. The thread, in her hands, becomes line, another kind of drawing, another kind of writing. Together, these artists, miniature painters, digital innovators, and textile storytellers, demonstrate that the arts of the book are not confined to paper. They live in cloth, metal, code, and touch. The miniature’s essence, patience, repetition, precision becomes a shared language of care across media.

The verse: If you are new, show me a new morning, a new evening. It is both a challenge and a benediction. The artists respond by reinventing what it means to write, to remember, to begin again. In an age of digital transience, Kitab Ghar reasserts the physicality of the book as a site of resistance and reverence. These are not just pages to be read but spaces to be inhabited, tactile, spiritual, and deeply human. Within this “house of books,” each artist writes not to preserve the past but to make it breathe anew. In the end, Kitab Ghar stands as more than an exhibition, it is a collective manuscript of memory and imagination, a reminder that to make art is to write oneself.

Syeda Farwa Batool holds an M.Phil in English Literature and an art critic based in Lahore.