The exhibition showcases nine emerging artists who use art as a tool for inquiry, turning creative practice into research-driven exploration.

“Investigative aesthetics is not only about revealing the truth of a situation but about constructing new ways of sensing and assembling the world.”

-Eyal Weizman and Matthew Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth

Investigative Aesthetics presents itself as an open proposition, a gathering of practices that challenge what it means to make, to research, and to know. Curated by Zarmeene Shah, the exhibition brings together nine recent MPhil graduates from the Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Anum Sanaullah, Ghania Shams Khan, Hallah Khan, Mahreen Zuberi, Naveed Siddiqui, Sana Naqvi, Shamama Hasany, Syed Safdar Ali and Zoya Abbas. Their work emerges from long investigations that transform the studio into a site of inquiry. The works are displayed as nodes within a broader conversation about the relationship between practice and knowledge, aesthetics and ethics, and the responsibilities of artistic research in the contemporary moment.

Drawing its title from Eyal Weizman and Matthew Fuller’s Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth, the exhibition engages a mode of artistic inquiry that blurs the boundaries between art, activism, and forensic research. Weizman and Fuller conceptualize investigative aesthetics as a framework through which art participates in the production of truth by assembling fragments, traces, and testimonies into new forms of collective understanding.¹ “Aesthetics,” they write, “is not only a matter of beauty but of sensibility: of how things come to be known.”² The exhibition extends the investigative not only as a methodology but as an ethics, a way of looking, listening, and feeling that makes visible the hidden entanglements of the world.

Shah’s curatorial essay situates the show within a pedagogical and planetary ethos. She invokes Gayatri Spivak’s notion of haq, the “para-individual structural responsibility into which we are born”, to frame the artist’s role as one of accountability toward their environment, histories, and communities.³ The exhibition thus positions the artist as investigator, archivist, interventionist, and narrator, one who moves fluidly between disciplines to produce new modes of knowledge. By framing creative practice as inquiry, Shah resists the tendency to treat research as a supplement to making; instead, research is shown to be inseparable from form, material, and process.

The nine practices gathered under Investigative Aesthetics articulate different ways of knowing through making. Naveed Siddiqui’s Reshaping Power revisits the socio-spatial traumas experienced by the Urdu speaking community of Karachi, Nazimabad, during the 1990s. Working through collage and corrugated material, Siddiqui reconstructs his neighborhood from memory and oral histories, revealing how space becomes a repository of violence, surveillance, and marginalization.⁴ His work resonates with Weizman’s idea of the “forensic architecture” of everyday life, where material traces act as witnesses to invisible systems of control.⁵ Yet, Siddiqui’s intervention departs from the empirical language of forensics: his evidence is affective, tactile, and embodied. Through texture and layering, the resulting works are interpretations of his neighbourhood, distorted, fragmentented and surreal.

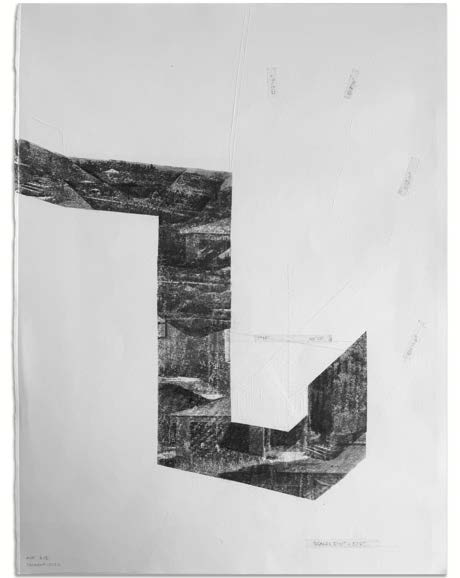

Similarly, Ghania Shams Khan’s Shape of a Shadow operates within an expanded field of architecture and mysticism. Drawing from Ibn Arabi’s cosmology of the world as “God’s shadow,” her graphite and emboss drawings evoke an experience of the sacred through light and spatial absence.⁶ Khan’s practice reflects a phenomenological turn in architectural thought, where space is apprehended not only through the senses but through states of being. By situating her drawings within the landscapes of Balochistan, she transforms the act of architectural representation into a form of contemplation. In contrast to the evidentiary impulse that drives much of investigative aesthetics, Khan’s inquiry is inward and reflective, a search for the unseen within the visible. Her work reminds us that the investigative can also be devotional, and that understanding may arise as much from silence as from exposure.

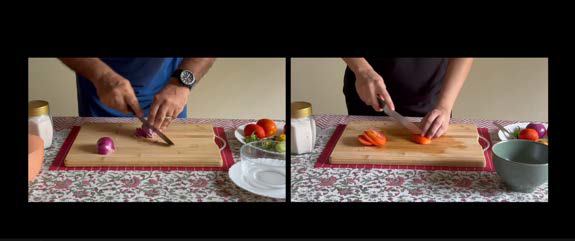

Halah Khan’s exploration of generational trauma and Sana Naqvi’s study of matrilineal textile traditions both engage what might be termed intimate investigations. Halah’s video performances translate the biological inheritance of trauma, informed by research in epigenetics, into a visual language of repetition and haunting.⁷ The body becomes a site of transmission and repair, a vessel that carries both memory and mutation. Naqvi’s Taarkashi similarly traces the genealogies of women’s labor through needlework, positioning craft an archive.⁸ Her act of stitching is as much analytical as it is affective, a method of tracing intergenerational pain while reconstituting it into resilience. Both artists mobilize domestic materials and gestures to construct counter-histories of care, reclaiming the forensic for the private sphere. Their practices align with Weizman’s notion of “counter-forensics”, the reappropriation of evidence from within the marginalized and the intimate, where the personal becomes the site of epistemic resistance.⁹

Mahreen Zuberi’s Basic Drawing Exercises explicitly revisits the colonial legacy of art education in South Asia, tracing how the shift to drawing from a priori, a drawing based on reasoning and knowledge gained independently of experience, such as through logic and mathematics to drawing from observation reconfigured the epistemology of seeing.¹⁰ By reconstructing early art school exercises and translating them into sound and installation, Zuberi discusses how modernist visual training continues to shape perception, marginalizing non-visual and intuitive forms of knowledge. Her critique resonates with the exhibition’s broader call to reimagine the very structures through which art is taught, learned, and transmitted.

Syed Safdar Ali’s practice probes the unstable relationship between perception, meaning, and truth. In asking, “What is the religion of the dome?” he transforms a familiar architectural form into a site of questioning, one that refuses singular interpretation. His ceramic and terracotta works embody what Weizman and Fuller describe as a practice that reconfigures how truth is produced and perceived, not through revelation alone, but through the assembling of fragments, materials, and perspectives. By allowing ambiguity to persist, Safdar’s investigation exemplifies the kind of aesthetic inquiry that operates not to explain, but to unsettle.

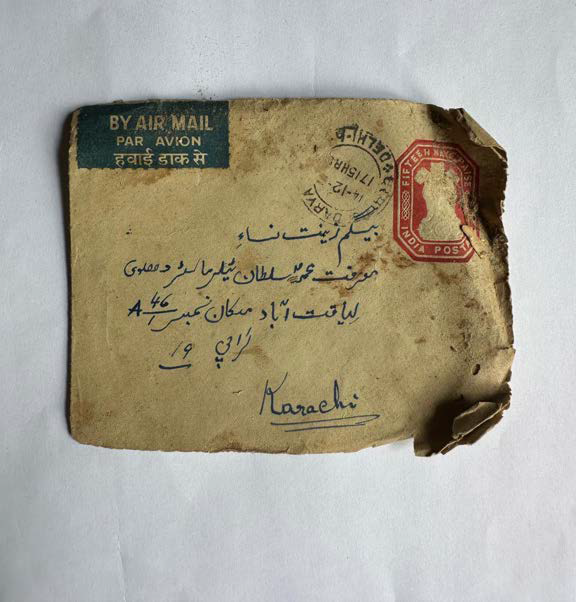

In a different register, Shamama Hasany and Zoya Abbas turn their investigations toward the affective geographies of Karachi, the home, the bazaar, the street, as spaces of emotional and creative negotiation. Hasany’s I Will Write to You About the World and Small is Beautiful weave together monotypes, body casts, and writing to explore shelter as both a spatial and psychological condition.¹¹ Her inquiry into care, vulnerability, and selfhood resonates with Shah’s curatorial question: “Can we begin to rethink our positions from that of spectator to that of one who deeply engages beyond the immediate aesthetic of the image-object?”¹² Abbas, through her epistolary installations and video works, transforms loss and absence into generative sites of relation.¹³ Her process of letter writing and archival reconstruction evokes the very structure of the investigative: fragmentary, recursive, and always unfinished.

These varied practices demonstrate that investigation need not always lead to revelation or resolution. Instead, they highlight the value of sustained attention, of looking slowly, of dwelling in ambiguity. The exhibition reclaims slowness as a method, insisting that to investigate is also to care, to listen, and to be implicated.

In a time when truth itself is fractured by spectacle and disinformation, Investigative Aesthetics proposes a different kind of truth-making, one rooted in care, attention, and relationality. It reframes art’s social role not as representation but as method: a way of knowing that is embodied, situated, and accountable. The participating artists, through their varied investigations, expand the field of artistic research beyond the institutional and into the intimate, the sensory, the spiritual, and the political.

In the context of Karachi, a city defined by its multiplicities, erasures, and constant negotiation, the exhibition feels urgent. It suggests that to investigate is to belong; that to create knowledge is to take responsibility for one’s place within the world. As Shah writes, the task before us is to “rethink our relationships with our practices, our worlds, our communities, and indeed with our own selves.”¹⁸ Investigative Aesthetics succeeds precisely because it refuses to offer resolution. Instead, it insists that the work of investigation, like that of care, must remain unfinished.

- Eyal Weizman and Matthew Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics: Conflicts and Commons in the Politics of Truth (London: Verso, 2021), 8.

- Ibid., 12.

- Zarmeene Shah, “Curatorial Statement,” Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue (Karachi: Koel Gallery, 2025), 4; Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Imperative to Reimagine the Planet,” in An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 338.

- Naveed Siddiqui, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 24.

- Weizman and Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics, 47.

- Ghania Shams Khan, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 18.

- Halah Khan, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 20.

- Sana Naqvi, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 28.

- Weizman and Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics, 53.

- Mahreen Zuberi, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 22.

- Shamama Hasany, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 30.

- Shah, “Curatorial Statement,” 5.

- Zoya Abbas, “Artist Statement,” in Investigative Aesthetics Exhibition Catalogue, 32.

- Shah, “Curatorial Statement,” 6.

- Weizman and Fuller, Investigative Aesthetics, 16.

- Ibid., 78.

- Shah, “Curatorial Statement,” 7.

- Ibid., 8.