The group exhibition held at the Koel Gallery invited artists to respond to the metaphors of wood. The show displayed an array of astounding art.

Ingrained Wood in a Cross Section of Time, curated by Zahra Ebrahim and Naila Mahmood at Koel Gallery, asks creative practitioners of varying disciplines to respond to the material and metaphors of wood. The curatorial statement situates trees as symbols of memory and belonging, framing wood as both sacred material and medium of transformation. Stepping into the gallery, one is struck by the breadth of material investigation, each artist allowing wood to speak in its own register.

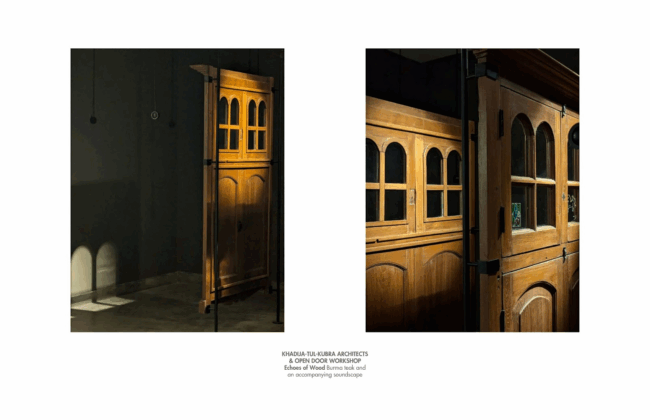

Echoes of Wood Burma teak and an accompanying soundscape

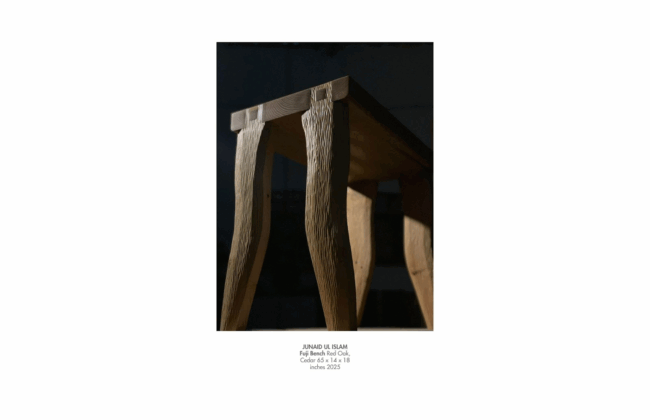

Ingrained is sensorial, textured, and carefully crafted. The exhibition develops a wide-ranging vocabulary for wood. Arshad Faruqui’s The Basic Stool simplifies the form of a stool, round textured wooden seats resting on three legs, so that the material takes center stage and is not disguised in the artistry. Junaid ul Islam’s Fuji Bench relies on Kumiki, a centuries-old Japanese joinery method that interlocks pieces without nails, glue, or fasteners. A red oak plank appears to hover above cedar legs whose curves echo human forms. Fraz Mateen’s meticulous and delicately framed ink drawings of Jamun, Keekar, and Deodar trees link the everyday familiarity of wooden furniture to the living forests from which it originates. Zoral Naik’s photographic project Autopsy treats felled trunks like forensic evidence: rings become seismic fault lines, while lumberyard markings resemble bureaucratic inscriptions on the dead. Sound adds another register through Asif Sinan’s soundscape Where the Trees Sing and Khadija-tul-Kubra’s collaborative installation with Open Door Workshop, Echoes of Wood, where teak doors suspended in space vibrate with sonic memory. Across these works, wood is touched, drawn, carved, suspended, sounded, and photographed, producing a tactile polyphony that circles back to the question of what its grain continues to hold.

The exhibition also raises, albeit quietly, questions that feel impossible to ignore in our current moment. Pakistan is consistently ranked among the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world. Each summer, we brace for heatwaves and increasingly destructive monsoon floods. Just a few days after the show opened, Karachi’s roads were flooded by the monsoon. In such a context, to speak of wood only as memory and metaphor risks turning away from the urgency of the environmental crisis. Trees are not just carriers of myth and lineage; they are our defense against catastrophe. Their depletion is already reshaping our landscapes into terrains of precarity. The exhibition offers an insightful perspective on the histories of trees, nature, and wood through the arc of human and urban development, but in ways that feel somewhat decontextualized. In Karachi, where trees are routinely sacrificed to urban development, the show resonates uniquely. Trees are not only there to provide shade or as obstacles to progress and capitalistic development, but companions to our everyday lives, and the show reminds us of a world that was much greener than it is now. Ingrained doesn’t let us forget this contradiction: how trees hold us even as we betray them.

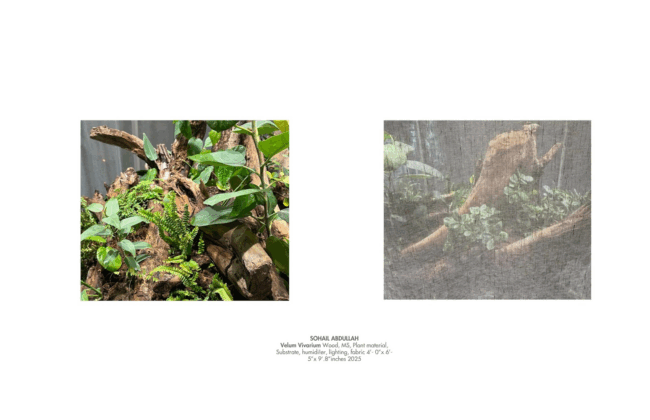

Several works in Ingrained touch this nerve more directly. Nida Bangash’s Living Archives paints displaced trees in delicate watercolour and gouache, the bergamot, the mandarin, the olive, tracing histories of colonial extraction and occupation that are still alive in Palestine and beyond. Sohail Abdullah’s Velum Vivarium is perhaps the most overtly ecological, staging a trunk salvaged from a Karachi storm as a site of decay and regeneration, sustained artificially by mist and light, a fragile ecosystem under threat. Usman Saeed’s Peelak Songs, links the much-maligned Conocarpus tree to the songs of golden orioles, insisting that even invasive species carry value in an era of ecological precarity.

Anushka Rustomji’s Rooting (I) and (II), one of the most conceptually and visually striking works in the show. Drawing on the mythical Waq-waq tree from the Shahnameh, her graphite canvases entwine human and arboreal forms. The Waq Waq tree is a legendary tree from Persian and Arabic folklore that bears human-like fruit or beings that scream “Waq-Waq”. Depending on the version of the tale, the fruits can be heads of men, women, or even monstrous animals. The Waq-waq, which foretold Alexander’s mortality at the height of conquest, is here reframed for our time: as a warning against the extractive economies that have propelled us into the Anthropocene. Rustomji’s work refuses nostalgia. Instead, it asks us to see the continuity between conquest, resource extraction, and ecological collapse, a reminder that climate change is not just a natural disaster, but a political one rooted in histories of empire and capitalism. The canvases were hung on simple wooden panels, drifting softly with the breeze, the corners and edges of the canvases left as untamed as the roots drawn in them, adding an extra layer to the work

One way to situate Ingrained is through Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, which calls for listening to the “grammar of animacy”, recognizing trees not as objects but as beings with agency, wisdom, and reciprocity. Much of the exhibition’s language gestures toward this: wood is treated as sacred, storied, alive. Yet as Kimmerer insists, reverence without reciprocity is incomplete. To truly listen to trees is not only to marvel at their endurance but to acknowledge our responsibility to them. As Anna Tsing reminds us in The Mushroom at the End of the World, the Anthropocene cannot be narrated without attending to capitalism, extraction, and uneven vulnerability, dynamics acutely visible in Pakistan’s climate reality.

The exhibition remains ambivalent. Its strength lies in its reverence, in the way it treats wood as sacred and alive. Without confrontation reverence feels insufficient when forests are being cleared at alarming rates, when communities across Pakistan are forced to migrate because of flooding, when air and water quality worsen daily.

Ingrained is materially rich, conceptually layered, and deeply moving in places. By dwelling on intimacy and memory, it is grounded in the sensorial and the symbolic. It asks us to listen to the grain of wood, to hear the whispers of memory etched into its surface, to feel the sanctity of material we too often consume thoughtlessly. But it also leaves one unsettled, lingering on the tension between myth and crisis, metaphor and matter. To listen to wood today is also to listen to the sound of trees perishing. The question is whether we are ready to hear it.

Glossary:

- Grammar of Animacy – From Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. Refers to Indigenous ways of speaking that treat plants, trees, and other beings as animate subjects (“who”) rather than inanimate objects (“it”), emphasizing reciprocity and respect.

- Anthropocene – A contested term in environmental humanities describing the current geological epoch shaped by human activity, particularly industrialization, extraction, and ecological collapse.

- Precarity – As developed by scholars like Anna Tsing, this term describes the condition of living in uncertain and unstable worlds, often intensified by capitalism, climate change, and displacement.

- Extractive Economies – Systems of resource use driven by colonial and capitalist logics that prioritize profit and expansion, often at the expense of ecosystems, indigenous knowledge, and long-term sustainability.

- Environmental Justice – A framework linking ecological crises to social inequities, emphasizing that the most climate-vulnerable communities (often in the Global South, including Pakistan) bear the brunt of environmental degradation.

Anna Lowe Haupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015). ↩