Haroon Shuaib speaks to the veterans hailing from Balochistan’s art scene for an in-depth essay focusing on the rise of art in the region.

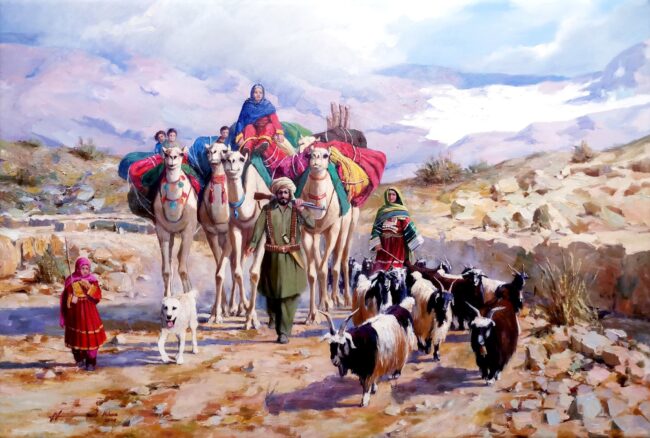

A veil of obscurity shrouds Balochistan’s artistic lineage. Whispers of the ancient resonate from Musakhel’s caverns, where Upper Paleolithic hands etched stories into stone around 18,000 BC, only to vanish into the vast, silent expanse of subsequent ages. Residents of Mehrgarh had discovered metallurgy and were making figurines to worship and revere and ceramics with celestial motifs, fish, ibex, lions and bulls painted to store food and liquids they grew and collected. First half of 20th century however, witnessed scattered flickers of individual brilliance: Syed Aziz Jan of Pishin, a chronicler of the quotidian, sculpting miniature figure to freeze visions of prayer or cockfights, alongside towering Dussehra effigies, each a temporary monument to faith. Zainuddin, a virtuoso of reverse glass painting, captured fleeting moments in vibrant hues. Then there was Deepak, originally from Bombay, immortalizing iconic figures like Ataturk on canvas. Yet, these solitary beacons struggled against the prevailing dimness. While it is believed that Sadequain lived in the province before he became known and Saeed Akhtar and Ijazul Hasan too, spent their childhoods here, until the latter decades of the 20th century, the artistic landscape of Balochistan remained largely defined by the practical strokes of signboard artisans, such as Shafi Sahib, Lala Aziz and Khalid Mengal. Their craft confined to a visual language more functional than expressive.

In Quetta, the University of Balochistan etched its name into history as within its walls in 1984, a vibrant anomaly took root: a department dedicated to the muses of fine art. This cultural genesis was the brainchild of three passionate artists from the province, Syed Jamal Shah, Akram Dost Baloch, and Kaleem Khan, each of them a graduate of the National College of Arts. Jamal Shah, in an interview once recounted a serendipitous Quetta sojourn. Between thesis break at the NCA, a chance encounter with Vice Chancellor of University of Balochistan Akbar Shah, his distant kin, sparked a dormant ember. “My heart yearned to sow the seeds of artistic expression in Quetta,” he revealed. From this yearning, a feasibility report blossomed, and with the Vice Chancellor’s nod, the department materialized. Born in Quetta, Jamal Shah’s roots anchored in Pishin, but his journey soon extended beyond the provincial borders. A British Council scholarship propelled him to the hallowed halls of the Slade School of Art, where his artistic lexicon expanded, embracing a global resonance. His creative spirit, a restless voyager, further navigated the realms of acting, filmmaking, and music. He later founded Hunerkada College of Visual and Performing Arts in Islamabad in 2019, and continued to serve the arts as the head of the Pakistan National Council of Arts and recently as the Caretaker Federal Minister for National Heritage and Culture.

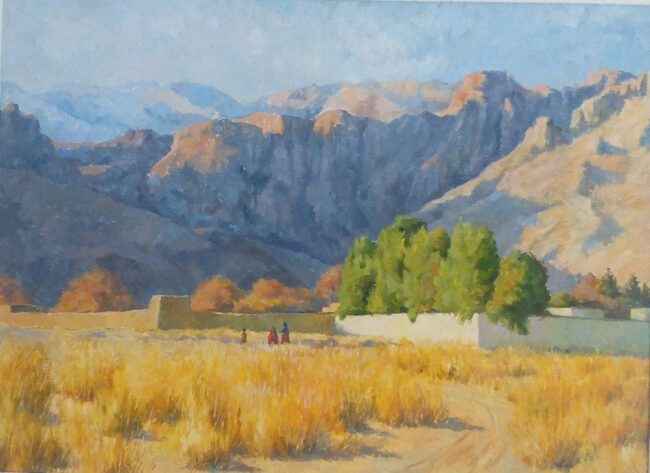

While Jamal Shah’s journey took him away from Balochistan, for Akram and Kaleem, the heart of their creative work remained firmly in the rugged landscape of their land, nurturing the fledgling fine arts department at the University. Akram, originally from Naushki, found his muse in the beauty of order amidst chaos that defined his surroundings. His artwork is a testament to the essence of Balochistan, capturing its faces, features, and intricate aesthetics. Every stroke on his canvas seems to echo the deep, yet often overlooked harmony that emerges naturally from the untamed landscape. Each forlorn set of piercing eyes, ask some pertinent questions and challenge the conscious of the beholder. Kaleem Khan, on the other hand, sought inspiration from the very earth beneath his feet — Balochistan’s rugged and wild terrain. His connection to the land is undeniable, and his work has since earned him a reputation as one of Balochistan’s leading landscape artists. As he later took the helm of the department at the University of Balochistan, his impact on the artistic community became even more profound, cultivating a new generation of artists who were equally inspired by the land that shaped them. Reflecting on the early days of the department, Kaleem shares, “We got the best possible students in the first batch. There were about 15 of them, and they were all incredibly passionate and committed. The students that graduated from University of Balochistan as artists continued to paint fervently.”

One of the artists to graduate from the university at that time is Abdul Hameed Baloch who today runs The Shal Art Gallery with his two disciples and friends, Ishfaq Shah and Mazhar Baloch. The Shal Art Gallery is one of the handful of art galleries in Quetta and is housed within the Brahui Academy. Hameed hails from Kalat and like his teacher Kaleem, excels in landscape painting. Landscape as a subject, and references to indigenous aesthetic elements, from traditional weaving, embroidery and jewelry, continue to dominate the work of most artists from Balochistan. Dozens of strikingly painted landscapes adorn the walls of Shal Art Gallery, testifying to the talent and dedication of Hameed, Ishfaq and Mazhar, but there are hardly any visitors to cherish their work and even fewer buyers. Hameed sustains his gallery by tutoring students and preparing them for admission tests of NCA and other art colleges.

Fazil Mousavi, a master artist belongs to Hazara community and is very well respected in the art circle of Quetta, thanks to his kind demeanor and wealth of knowledge as much as his equally mesmerizing art. Mousavi is a master of traditional calligraphy but with time has transitioned his art to a find unique expression merging Persian text with inventive and enhanced dimensionality, using blurry washes, scribbles, and gold leafing, adding a much deeper meaning and effect to his compositions with very cleverly crafted negative spaces. Fazil too has mentored many students, mostly belonging to the persecuted Hazara community, and who were unable to freely go out of their confined neighborhood due to the threat of lingering sectarian violence occurring against them. He guided and honed their creative talent preparing them so they find it easier to secure admissions in formal art intuitions within the country and abroad.

Mubarak Shah’s Resham Art Gallery on Jinnah Road, also doubling up as a teaching institute, is a comparatively more recent establishment. Mubarak, nephew of Jamal Shah and a lecturer at the University of Balochistan, is a practicing artist with a very innovative and unique visual language with distorted tormented faces yearning to find a true identity, jumping out of his canvases, sometimes screaming and at other times demanding attention through their striking colors. While Mubarak has obviously made a departure from the placid themes that have been mostly prevalent, the students at his gallery seem to tread more carefully when it comes to breaking the norms through choosing unconventional mediums or subjects.

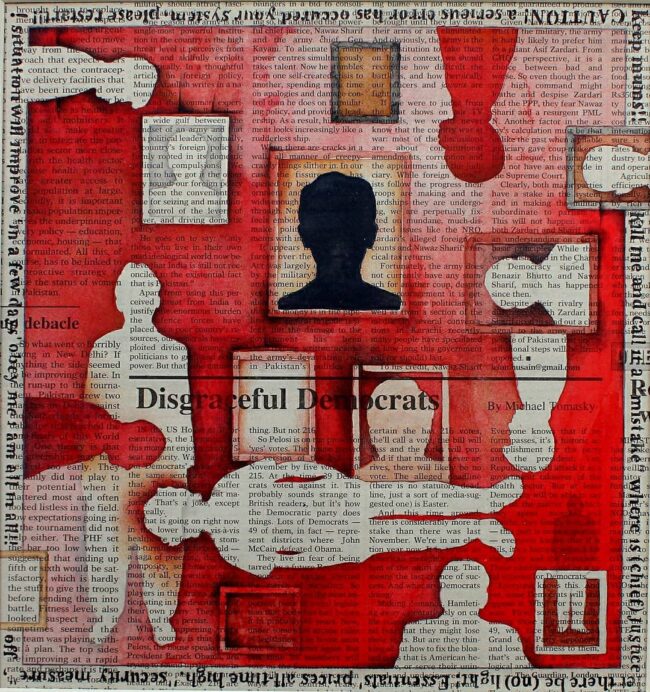

Asif Kasi, a graduate of the University of Balochistan, also hails from Quetta. His work though at the surface may seem full of color but if one cares to look deeper and longer, questions of strong unfair systemic exploits slowly emerge out of his canvases. He through his art asks questions of unjust resource allocation and elite capture when the subjects pop out of their colorful backgrounds and one realizes that the malnourished and famished souls are only camouflaged behind these color laden and deceitful labyrinthic facades by those who hold the power.

Almost two decades after the advent of the fine arts department at the University of Balochistan, the second university of the province and Quetta city, Sardar Bahadur Khan Women’s University, established in 2004, introduced a fine arts programme. Since it is a women’s only university its artists have mostly remained obscure.

In fall 2010, fine arts department at Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and Management Sciences (BUITEMS) also introduced a four-year BS course in various disciplines of Arts. Naseeb Khan, who hails from Kuchlak, was part of the department’s first graduating class and is currently part of the faculty of his alma mater. He paints life-scapes. People and places as they transpire around him and moments frozen in time make it to his vivid, colorful canvases.

But things have obviously changed since then and the speed of change is ever increasing. Currently Meraj Mohammad heads the fine arts department at BUITEMS. The university has since introduced some really path breaking trends through a carefully curated faculty. Hammal Khan from Turbat District, a graduate of NCA is currently teaching at BUITEMS and has broken the confines of canvas to explore multimedia art. He is experimenting with video, installations, and performance art. Syed Sajjad Hussain, Mousavi’s son, a graduate of the NCA, is a neo-miniaturist and is using miniature to depict the impact of violence and how it impacts people’s lives and psychologies. Himself having survived violence that was near fatal, Sajjad’s miniature is loaded with messages of resilience. Abdul Wahab teaches sculpture, which in the conservative society of Balochistan is a daring undertaking. Imran Ali mentors students in printmaking and it is surprising how many youngsters are actually interested in this unconventional medium and a clear indication that the young artists are increasingly motivated to break away from the traditional confines of how art has been viewed and practiced in their province and adopt more contemporary dimensions and expressions.