Two distinct strata ran through Zahra Asim’s exhibition of paintings and combinators, waiting, so to speak, to be uncovered and explored — on the one hand, theories of perception, and the other, of architectonics. Needless to say, these concurrencies did not so much announce themselves straightaway in any written or stated form, as might have been the case in an exhibition produced by an artist more familiar with these somewhat objective ways of describing things. Indeed, beginning with the strategically-located canvas titled Majestic Mess, these territories were immediately presented to the imagination in the depiction of what seemed to be a very cluttered living room in most urban homes, with a goodly third foregrounded by the leaves of a large and sprawling plant.

If one were to concur with Maurice Merleau-Ponty, then reality—or more precisely, cognitive experience-is – is built up of ‘association’ and the ‘projection of memories’. He wrote: “Perception is built up with states of consciousness as a house is built with bricks, and a mental chemistry is invoked which fuses these materials into a compact whole. Like all empiricist theories, this one describes only blind processes which could never be the equivalent of knowledge, because there is, in this mass of sensations and memories, nobody who sees, nobody who can appreciate the falling into line of datum and recollection, and, on the other hand, no solid object protected by a meaning against the teeming horde of memories.”

Architectonics refers to the study or system of structure and organization—how parts are related to a whole—across various disciplines. The term originated from the Greek architekton, meaning “master builder” or “chief craftsman.” Though rooted in architecture, it has been used metaphorically in philosophy, literature, art, and science. Thus, knowledge needs to be arranged logically and coherently in philosophy, with each part supporting a rational whole. For example, Kant built a “system of transcendental philosophy” through a formal framework in his Critique of Pure Reason. In Aesthetics and Literary Theory, compositional order refers to the internal structure of a text or artwork—how form, content, and conceptual frameworks are related. Quite literally, in Architecture itself, it is the science of structure—how buildings are conceived, organized, and understood in terms of form, function, and symbolic meaning. In Art and Design (with which we were more properly concerned), it refers to the composition of a visual piece: how space, line, color, texture, and form are organized to create visual coherence.

In her statement, Asim herself wrote: “In my latest series of paintings, I delve into the intimate yet tumultuous realm of residential environments. These works unravel the essence of city-living, highlighting the intricate display between personal and shared spaces. Through these paintings, I aim to capture the dynamic energy and movement inherent to such areas, offering an authentic glimpse into the everyday lives of their inhabitants.” (Courtesy the Vasl Residency / Artist’s Statement) of concave and convex forms, and this lent a distinct sense of joie de vivre to her compositions, just as inventive rhythm and broken rhyme made up new poetry or spoken-word music. The bird’s-eye views of ‘Within These Walls’ and ‘Corner of Comfort’ merrily read out this versification, as did the near-abstract ‘Street of Memory’ with oddly invented lettering floating in space.

Similarly, her work suggested an ability to meld techniques as needed, and to not be too caught up with formalities either—in Wh’pers of Lived Spaces, the problem of depicting a lightbulb was resolved with a greatly insouciant textured swirl of paint that seemed to have persuaded the wall-fan to distort in agreement.

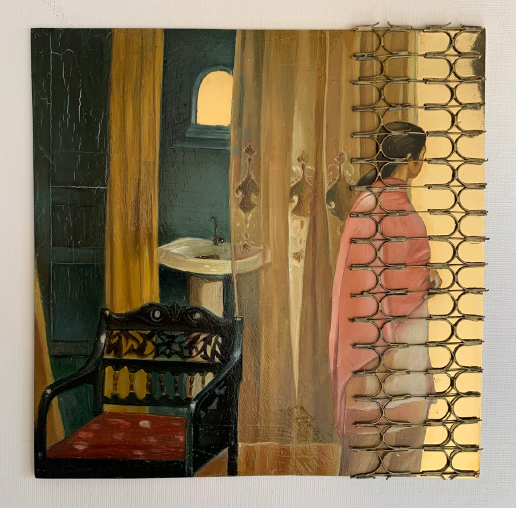

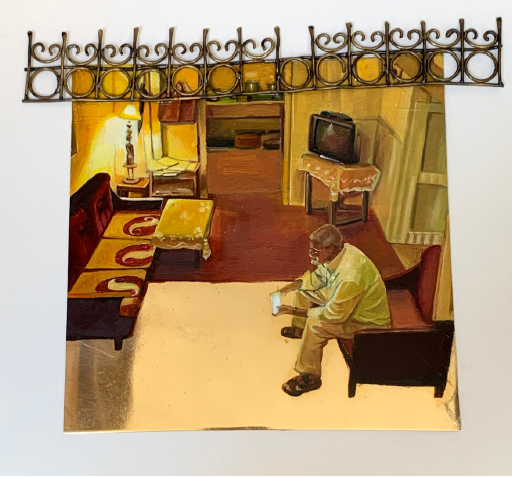

The series of small oil-on-brass plates titled ‘Made for the Soul’‘ broke with the conventions of painted canvas. Here, Asim’s apparent training as a jewelry-maker came to the fore, as the brass plates were essentially narratives combined with delicate metalwork echoing railings and grills ubiquitously attached to walls, balconies, and windows in dense urban environments. It might have been worthwhile to understand this melding of techniques as a paean to the issues of protection and privacy that inevitably arose in densely populated communities—matters both pragmatic and aesthetic at the same time.

As for colour, Asim confessed to being virtually haunted by saturated hues combined with near-normal tones. Almost all the works betrayed this exuberant character—a secret tendency to accept the reality of mixed lighting and illumination. Technically, electrical lighting could range from warm orange hues to cool clinical blues, or hallucinatory absinthe-greens even, but the human eye adapted quickly to produce the ‘correct’ tones for the sake of recognition and, even more importantly, crucial world-building that involved the emotions. In these matters, Asim instinctively abandoned any objectivity, reminding us of Merleau-Ponty’s critical observation:

“Once more seeking a definition of what we perceive through the physical and chemical properties of the stimuli which may act upon our sensory apparatus, empiricism excludes from perception the anger or the pain which I nevertheless read in a face, the religion whose essence I seize in some hesitation or reticence, the city whose temper I recognize in the attitude of a policeman or the style of a public building.”

In the same vein, speaking of ‘projections’, ‘associations’, and ‘transferences’ that were based on some intrinsic characteristic of the object, he wrote: “The human world ceases to be a metaphor and becomes once more what it is, the seat and as it were the homeland of our thoughts. The perceiving subject ceases to be an ‘acosmic’ thinking subject.” Zahra Asim then emerges as an artist who is not only a keen observer of her cosmos of perceptual concurrencies, but also one who reminds us to always attend to the only homeland each one of us could ever have.