بے صورت / Faceless – The title of this exhibition taken from a verse of Ghalib - koi surat nazar nahin aati - is an interesting play on words. Wh

بے صورت / Faceless – The title of this exhibition taken from a verse of Ghalib – koi surat nazar nahin aati – is an interesting play on words. While it literally translates to the word face-less, it contextually means how there is ‘no solution in sight’. What it creates is perhaps the opposite of a paradox. That the solution to everything is, in fact, all in the face. Both the literal absence of a face and the metaphorical absence of a solution, creates a conceptual tension that mirrors the complexities within Khadim Ali’s work. His artistic practice has long been concerned with the politics of visibility and erasure, where histories are rewritten, identities are manipulated, and the oppressed are rendered faceless within dominant narratives.

After years of absence from the local art scene, Khadim Ali’s long-awaited mid-career retrospective in Pakistan brings upon us a moment of reflection, celebration, and confrontation. His work, which has consistently engaged with themes of history, mythology, displacement, and war, finds new resonance in today’s socio-political climate. The retrospective offers an extensive journey through Ali’s evolving practice, showcasing how his visual language has seasoned while remaining rooted in his early influences and lived experiences. Curated by Zahra Khan of the Foundation ArtDivvy and displayed at the COMO museum in Lahore, this exhibition is not just an archival effort but a critical reflection on the continued pertinence of his art practice.

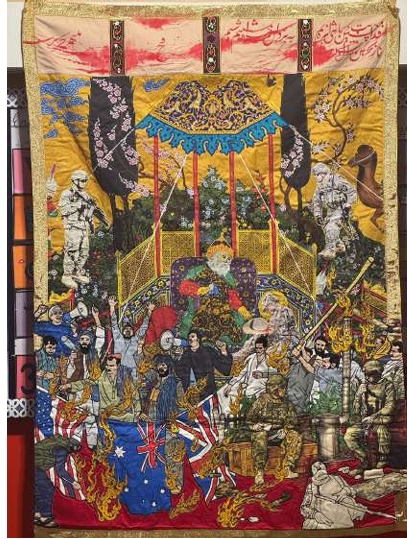

Khadim Ali’s work has undergone a consequential transformation over the years, shifting from a meticulous involvement with traditional miniature painting techniques to a broader, more interdisciplinary approach. Initially known for his delicate and intricate compositions that reinterpreted Persian and Mughal miniatures, Ali has gradually moved towards large-scale tapestries, murals, and sculptural installations. His work now embraces materiality in more experimental ways, incorporating embroidery, textiles, and even brass and steel.

For all those who have been a witness to Khadim’s Ali’s journey, we know that a defining feature of his work has been his use of recurring motifs, including demons, dragons, phoenixes, and angels—figures drawn from Persian and Mughal iconography that are recontextualized to address contemporary issues. The demon, historically emblematic of the ‘other,’ becomes a metaphor for marginalized communities, particularly those affected by war and displacement. Dragons and phoenixes, traditionally associated with destruction and renewal, function as allegories for the cyclical nature of violence and resilience and angels, often depicted as celestial protectors, assume ambivalent roles that problematize binary notions of good and evil. By using these symbols in a fluid and adaptive manner, Ali destabilizes hegemonic historical narratives, asking us to critically reassess the frameworks through which history is constructed and remembered.

Khadim Ali’s new tapestries (embroidery on fabric) continue his exploration of war, displacement, mythology, and identity, blending Persian miniature painting traditions with contemporary political narratives. These works, like his past ones, are deeply layered with iconography drawn from his Hazara heritage, South Asian storytelling traditions, and contemporary geopolitical conflicts.

Similarly, his new sculptural work ‘State Emblem’ critically examines the performative nature of state power through its fusion of ornate brass filigree, industrial steel, and symbolic drapery. Drawing from heraldic and religious insignia, the work highlights the fragility of authority, where grandeur is juxtaposed with rigidity and coercion. The white cloth, often associated with mourning and surrender, disrupts the emblem’s imposing verticality, hinting at the tensions between subjugation and resistance. Set against a green-lit background, the piece casts an eerie shadow, reinforcing the spectral, ideological presence of power. In the context of Khadim Ali’s retrospective, State Emblem functions as both a statement and a question: What does it mean to belong to a state that defines itself through rigid symbols of power? How do visual emblems contribute to erasure and exclusion? The work’s reminiscent ambiguity forces the viewer into an active role – questioning rather than passively absorbing.

With this exhibition, we see that Ali’s iconography does not remain static; rather, it shifts in meaning depending on its contextualization, reinforcing the idea that history is neither objective nor impartial but is continuously reshaped by dominant ideologies. In an era marked by geopolitical conflict, mass displacement, and ideological contestation, his visual lexicon remains acutely relevant. His oeuvre underscores the complex relationship between art and politics, signifying that art-making is invariably situated within larger structures of power and resistance. As one moves through the museum, they can see well how Ali questions the mechanisms of historical representation, foregrounding the role of visual culture in shaping collective memory and identity.

The significance of this retrospective exhibition is particularly pronounced given Ali’s trail as an artist whose career has been shaped by exile and international recognition. The return of his work to Pakistan after years of exhibiting globally constitutes a homecoming imbued with complex meanings. This exhibition provides us with an opportunity to engage with his artistic discourse within their own socio-political context, encouraging critical dialogues on themes of displacement, warfare, and cultural heritage that are deeply entrenched in Pakistan’s historical and contemporary landscape.

Curator Zahra Khan’s approach to this exhibition has been instrumental in positioning Ali’s practice within both historical and contemporary discourses. Rather than presenting his works as isolated artifacts, the curatorial strategy constructs a dialogue between different phases of his career. By putting together early works with more recent tapestries, brass and steel emblems and paintings, the exhibition expedites an analytical engagement with the evolution of his thematic and technical concerns. However, given the monumental scale of the tapestries, a more open spatial arrangement could have further enhanced the engagement with Ali’s intricate storytelling, allowing for a broader, more encompassing experience that does justice to the grandeur of his compositions.

In Ali’s work, the very concept of being faceless operates on multiple levels. His demons, angels, and mythical beings are often caught between states of recognition and distortion, reflecting how power dictates who is seen and who remains invisible. The exhibition itself, in revisiting his decades-long career, underscores how these questions have evolved – initially rooted in personal and collective histories of displacement and later expanding into broader critiques of global conflict and ideological hegemony. Within this context, the retrospective is a reminder that history itself is an arena of struggle, where visibility is both a privilege and a battleground. Khadim Ali’s legacy thus suggests that to be faceless is not simply to be without a solution, but rather to exist within a space where solutions are actively concealed, contested, and, at times, waiting to be uncovered through art’s critical gaze.