For many years, art history classrooms have heralded the unveiling of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon as a defining moment for modern art. The teaching of contemporary art has centered predominantly on the West, relegating regions such as South Asia to the periphery. This division can be understood through the core-periphery model, wherein definitions of modernity have been handed down from the West, often dismissing local artistic developments in non-Western regions.

South Asian artists, for much of the 20th century, fell into what art historian Partha Mitter has termed the “Picasso-Manqué syndrome” (International Departures, Devika Singh 10). This concept critiques how non-Western artists are viewed solely through the lens of imitation—where a South Asian artist producing modern art is seen as inherently unoriginal. Conversely, when artists pursued independent forms of expression, their work was often dismissed as unskilled and lacking the academic rigor of European masters. Addressing this imbalance requires decentering modernism and recognizing artists’ agency in diverse cultural contexts. In a decentered view of modernism, Paris, Rome, and London can be regarded as cultural centers alongside cities such as Mexico City, Tehran, and Lahore—shifting the narrative from a hegemonic, Eurocentric perspective.

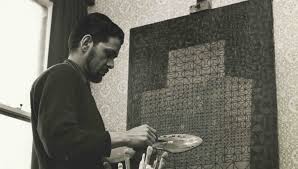

Anwar Jalal Shemza (1928–1985) offers a compelling case for reframing modernism. His work, celebrated internationally, has been displayed at prominent institutions such as Tate Britain, Tate Modern, and the 2024 Venice Biennale. Recent retrospectives from 2022, including “A Century of the Artist’s Studio: 1920–2020” at Whitechapel Gallery, “Postwar Modern” at the Barbican, and “Radical Landscapes” at Tate Liverpool, signify a growing recognition of Shemza’s contributions

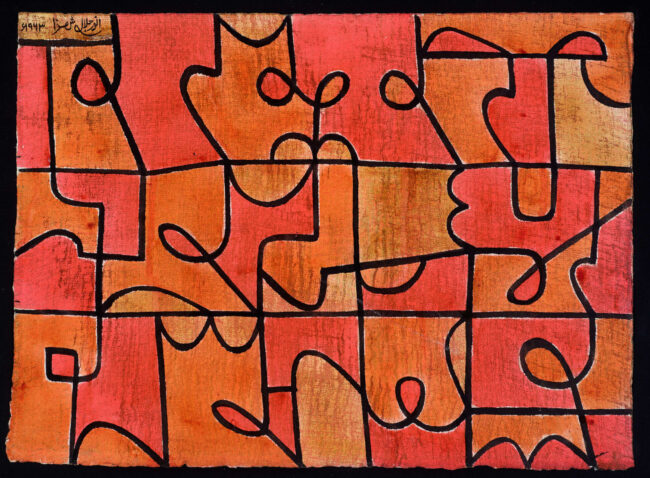

This posthumous acclaim underscores the importance of situating his work within an alternative history of modernism, one that highlights local artistic agency beyond the confines of Western Europe and North America. Shemza himself appears aware of the discourse involving non-Western art. This article focuses on his work displayed within Tate Modern’s The Shape of Words room, which explores the intersection of abstract art and calligraphy. The display contextualizes Shemza’s work within the broader decolonization movements of the mid-20th century—a period marked by increased transnational connections and political shifts. According to the museum label, this era was “filled with a sense of rebellion and innovation in the arts,” characterized by the “connections and exchanges” formed through transnational movements. The trajectory of a self within art can thus be viewed in the context of the artist’s original home, as well as through the home they have migrated to. In the context of independence, “artistic vocabularies” continue to be “rooted in local visual heritage”. Hence, script or calligraphy came to be associated with abstraction, as well as decolonisation.

Shemza’s trajectory exemplifies this dynamic. Born in Shimla, India, in 1928 to a Kashmiri and Punjabi family, he studied at the University of Punjab in Lahore before transferring to the Mayo School of Arts. Gaining domestic recognition in Pakistan for his artistic and literary achievements, Shemza was a member of the Lahore Art Circle dedicated to modernism and abstraction. In 1956, he moved to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art, returning briefly to Pakistan in 1960 before settling in Stafford. His transnational experiences profoundly shaped his artistic practice, blending Western modernist abstraction with Islamic artistic traditions.

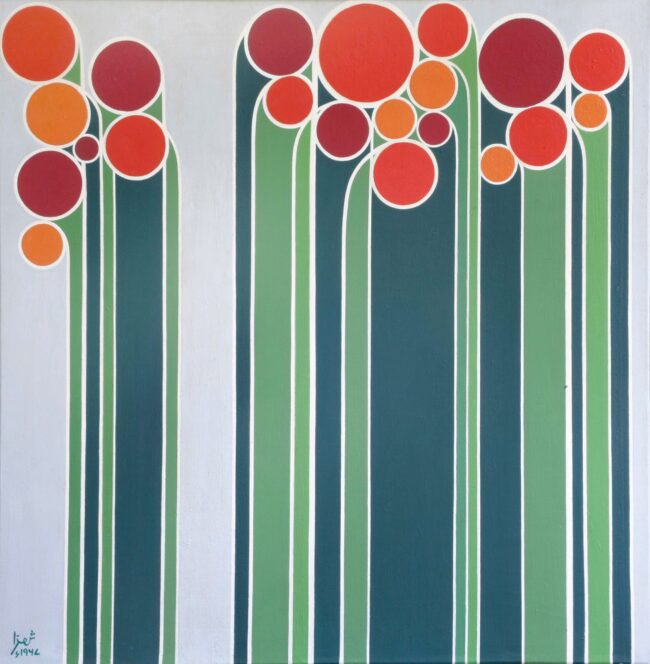

One of Shemza’s notable works, Meem Two, displayed at Tate Modern, is part of his Meem series. The painting incorporates the Urdu letter “meem,” exploring its form through contrast, color, and repetition. Dominated by two shades of gray, the composition features four variations of the letter arranged in a symmetrical circular configuration. The rhythmic interplay of shapes conveys fluidity within a structured, linear context. The letter “meem” serves as a personal reference to Shemza’s life, symbolizing his wife Mary (Art UK).

Shemza’s work provides insight into an alternative mode of thinking and a simultaneous awareness of hierarchical categorizations within the field of art history. A seminal text, “The Story of Art” by E.H Gombrich appeared as an introductory text to academics within the field from the year it was published in 1950 for decades onwards. In recent years, the work has only generated critique for possessing a Eurocentric focus. Shemza’s grandchild writes of his reaction to Gombrich’s critique of Islamic art, “He was so disheartened by one of Ernst Gombrich’s lectures in which the historian dismissed Islamic art as purely functional that he subsequently destroyed all his work and began an exploration of the modernist abstraction of Klee, Mondrian and Kandinsky” (Tate). Shemza’s fusion of abstraction and calligraphy seeks to overturn a hierarchy where Islamic calligraphy is dismissed as functional or decorative, as opposed to containing the status of ‘high-brow’ art with the means to evoke an emotional and aesthetic response

When considering modernism and art history itself as a field, it is significant to contextualize connection and exchange beyond the realm of the nation-state. Art historical frameworks often fall into the broader trap of stating that focus resonates with the history of a present-day nation. Shemza, himself was born in modern-day India, studied in Pakistan and migrated to the United Kingdom. He drew upon Klee, Mondrian and Kandinsky are the primary Western influences and traditional Islamic influences. Influence or art can seldom be placed in a vacuum or singular place. Transnational connections which exist beyond a singular artist or piece of work and their impact should be considered. When examining transnationality, questions of categorization remain. Shemza’s works are put into Tate Britain within a room focusing on Modern British art. This can be considered in the form of the overarching history of migration and transnational connections, with the field of art history being rethought and rewritten in a more inclusive, contemporary context.